There is no familiar equivalent in Persian for the cautionary maxim, “be careful what you wish for,” but it is an apt description for the predicament that Iran’s conservatives face as they assume full control of the Islamic Republic of Iran. The accession of Ebrahim Raisi on August 5 to Iran’s presidency is, according to hardliners, the first time a revolutionary administration is running the country.

This narrative conveniently ignores the administration of former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the anti-Western leader who was in charge with the full support of the parliament and other centers of power in Iran from 2005 to 2013. Perhaps that is because the experience did not turn out too well, despite much better circumstances. The country was not under severe sanctions, state coffers were flush with cash thanks to the high price of oil, inflation was moderate, and electricity and water services had not deteriorated to the point of provoking street protests. And, of course, there was no pandemic and Iran’s neighbor to the east, Afghanistan, was not imploding.

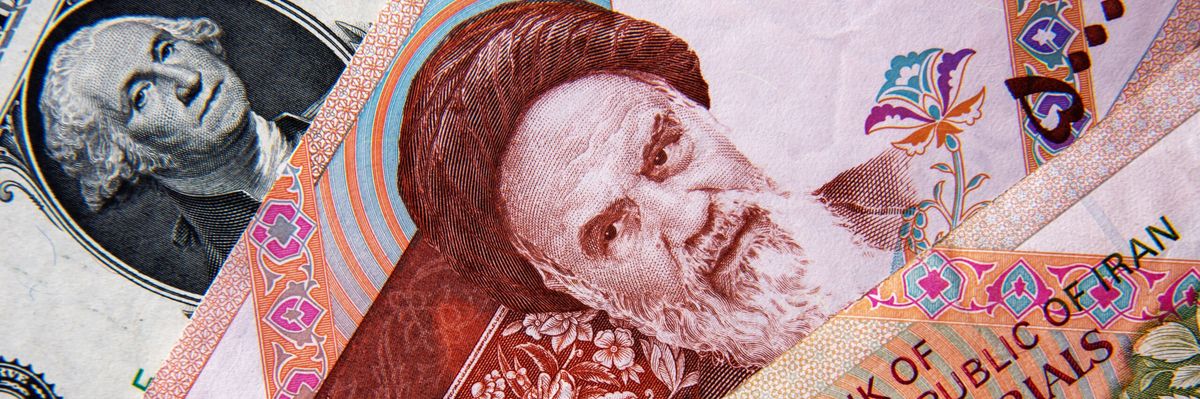

The conservatives are aware that the conditions are much worse this time around. The COVID-19 pandemic is in its fifth and most deadly surge, prices are rising at an annual rate of 40 percent while a gaping budget deficit makes it hard for the new government to harness inflation, let alone lead the economy out of its ten-year slump. All the while, Trump’s maximum pressure campaign continues to take its toll on the living standards of ordinary Iranians.

Their professed optimism in dealing with the economic crisis stems from a belief that it is in part caused by misguided western-oriented policies of the previous Iranian administrations led by reformist and moderate politicians. Reverse those, they say, and the economy will begin to grow. However, it is difficult to pin down a coherent model or set of ideas that explains how this would happen.

Many hardliners have blamed the 2015 nuclear deal (known as the JCPOA) for Iran’s economic ills, but most economists believe its revival should be the point of departure for Raisi’s economic program.

Consistent with the position of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei,, Raisi has emphasized the removal of sanctions as a top priority. The list of nominees for cabinet posts that he recently submitted to the parliament, included Hossein Amirabdolahian for foreign minister, which is seen in Tehran as a good sign for reaching an agreement with the Western powers. Initially, JCPOA proponents had feared the post might go to Saeed Jalili, the former chief nuclear negotiator under Ahmadinejad and a staunch opponent of the JCPOA. While Amirabdollahian lacks Zarif’s familiarity with the negotiating teams and his language skills are wanting, he will almost certainly enjoy more support from the Supreme Leader and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, or IRGC.

The gains from reviving the nuclear deal will be immediate and significant. To start with, it will unfreeze some $50-$100 billion of Iranian assets around the world and allow Iran to export more oil. This will go a long way toward plugging the giant gap in the budget for this fiscal year (2021-2022), projected to be 38 percent of total expenditures (5,233 trillion rials equal to about $45 billion based on the 115,000 rials per USD exchange rate used in the budget). This is particularly critical because the government cannot borrow abroad, and domestic borrowing is very costly due to high inflation. Any interest rate that would persuade the banks or the public to lend to the government while prices are increasing at more than 40 percent would destabilize the financial system.

Beyond this year, the economy would greatly benefit from access to the global financial system, which U.S. sanctions currently block. The depreciation of the rial under the pressure of sanctions has lowered real wages and boosted local production, especially in manufacturing. According to the Central Bank, manufacturing grew by 8.1 percent last year while the GDP grew by 3.6 percent.

Last year’s growth was led by increased oil exports amid optimistic expectations in the second half of the year that Biden’s election might end or ease the sanctions. It may not last if the current negotiations reach a dead end.

Currently, local demand powered by import substitution is maintaining growth in manufacturing. For its growth to continue, Iranian producers must have access to the global economy, which will be achieved if a deal is reached in Vienna. A deal will also boost manufacturing production that depends on the import of intermediate goods; it will ease trade as well as increase foreign exchange with which to buy intermediate inputs.

Although reaching a deal in Vienna will significantly benefit Iran’s economy and get Raisi closer to fulfilling his extravagant campaign promise of one million new jobs and one million new homes each year, he may be satisfied with a repeat of last year, when the economy added about 700,000 jobs and attained moderate growth. This is the fallback position that Raisi’s economic team is considering rather than a collapsing economy imagined by Iran’s opponents.

However, repeating last year’s performance will depend on the soundness of the government’s economic policies. Raisi’s proposed appointments signal a sharp departure from the market-based policies of his predecessor. Quite a few of them served under Ahmadinejad, including Farhad Rahbar, Raisi’s chief economic advisor, who headed the Management and Plan Organization in the first Ahmadinejad administration and who is expected to get the job of vice president for economic affairs. The proposed appointee for MPO, Masoud Mirkazemi, also served under Ahmadinejad. He is not an economist, so economic policy is likely to be determined by Rahbar and the proposed minister of economy and finance, Ehsan Khandouzi. Both are critics of capitalism, believe in looking inwards, and are skeptical of free markets, but understand the importance of global connections and private-sector led growth. They also favor greater redistribution that would reverse the trend under former President Hassan Rouhani’s administration of rising inequality and poverty.

Significantly, conservatives and hardliners have in the past opposed enacting laws necessary to take Iran out of the blacklist of the FATF, the international anti-money-laundering watchdog. Raisi’s economic team has argued that increasing transparency of the Iranian banking system is important but must await the removal of sanctions, when Iranian traders are not busy evading them. Without satisfying the FATF standards, even absent sanctions, foreign banks will be reluctant to accept transfers from Iranian banks not knowing their origin.

The economic team of the “first revolutionary government” of the Islamic Republic faces formidable challenges. In such circumstances, reaching the lofty goals of creating one million jobs and building one million new homes each year and reducing poverty requires more than revolutionary zeal. President Raisi would do well to listen to the more pragmatic voices in his team and steer the economy to calmer waters before taking actions recommended by his more revolutionary supporters.