Since taking office in January, President Joe Biden has promised to “reimagine” U.S. foreign policy and its purpose after Donald Trump. On some initiatives, like repeal of the 2002 Authorization to Use Military Force, rejoining the nuclear agreement with Iran, and the Paris climate discussions, the administration has been successful. But on other policies, Biden’s record is mixed. Biden’s withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan is notable, but it’s also evident that the United States will operate drones and intelligence operations in the region in perpetuity.

As other writers have noted, Biden’s domestic agenda appears more promising. Left-leaning commentators have made comparisons to transformative Democratic leaders like Franklin D. Roosevelt and Lyndon B. Johnson, whose New Deal and Great Society brought monumental reforms like Social Security, “food stamps,” Medicare, and Medicaid — popular programs on which tens of millions of Americans rely.

But Roosevelt and Johnson saw their domestic agendas sidelined by foreign wars — one a war of necessity (World War II), the other a war of choice (Vietnam). Both FDR and LBJ also framed domestic spending programs in the context of war, the expansion of the welfare state through the warfare state.

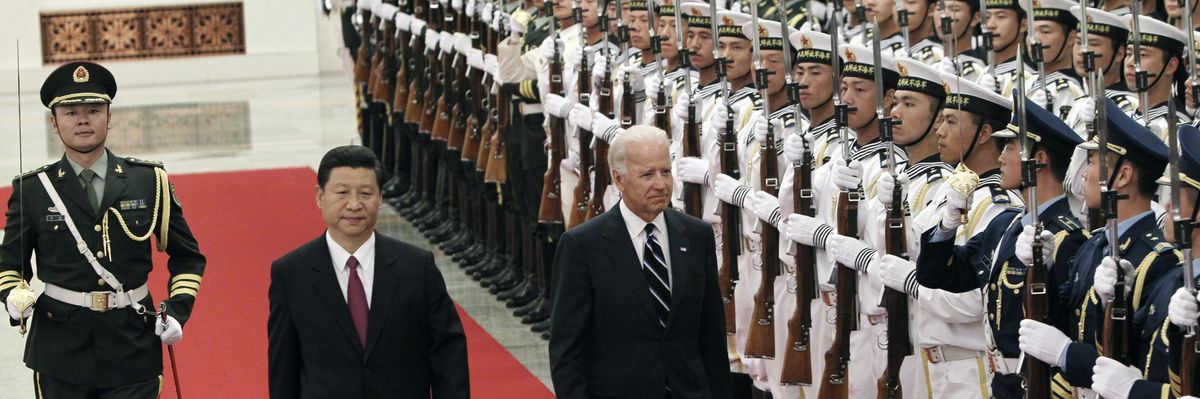

President Biden appears eager to follow in their footsteps. Like his Democratic predecessors, Biden has pitched investment in America’s people and cities as a foreign policy necessity — otherwise, America’s current great power competitor, China, will, as he has speculated, “eat our lunch” not only at home but around the world.

But as the Cold War between the United States and Soviet Union showed, linking American prosperity with foreign policy goals comes with huge costs — to ourselves and to the world. While it is evident that Biden intends to continue framing infrastructure spending as a national security issue, there is no reason that, going forward over the next year and half, domestic reforms must be justified as bulwarks to national security threats. Biden can offer alternatives to a defense budget which has made job creation and infrastructure spending dependent on a militarized foreign policy and endless war. A dollar spent on green energy technology, for instance, will benefit American workers and the economy multiples more than a dollar spent on arms for export. It will also benefit America’s foreign policy and its standing in the world.

Instead of comparisons to FDR or LBJ, perhaps a better model for Biden is found in Dwight D. Eisenhower. Ike’s experiences in wartime Germany convinced him that America needed its own autobahn system, for economic and military reasons. President Eisenhower and Congress pitched the bipartisan Federal Aid Highway Act of 1956 as a national defense measure — understandable enough in the 1950s, years out from World War II and amid conflict in Korea.

Both Republicans and Democrats agree that America’s Eisenhower-era infrastructure needs to be rebuilt. More worrying is that both are relying on the same Cold War-era politics and rhetoric to justify new spending, leading to the same issues that concerned Eisenhower. The China specter is a key feature of the current bipartisan infrastructure bill facing Congress — indeed, it might be the point of leverage that secures its passage. But given the military’s role in the U.S. economy — particularly when it comes to maintaining U.S. roads, bridges, and disaster response — as well as contractors’ influence in Congress, the new “bipartisan” infrastructure bill will have a heavy defense footprint and orientation.

The foreign and domestic policy consequences of that strategy are serious, as Eisenhower warned with his “military-industrial complex” speech in 1961, and Lyndon Johnson learned. Biden must not repeat the same mistake with other aspects of his ambitious domestic agenda, especially ones with direct foreign policy implications.

Climate change is first among them. Most experts agree that we should, and can, act to reduce or permanently eliminate fossil fuel emissions and create jobs at the same time. In fact, demilitarizing U.S. foreign policy would only complement a green infrastructure bill. The defense industry draws from the same labor pool as clean energy and infrastructure, for everything from R&D to the assembly line.

Rather than “dislocated,” these workers would be essential, and existing economies of scale means that more would soon be needed. Defense conversion could also train and employ millions of un- and underemployed Americans in an anemic post-COVID economy, providing both economic stimulus and lasting value.

Defense conversion can reprioritize how defense spending shapes America’s political economy and the Biden administration’s approach to the climate crisis. Like with the end of the Cold War, which saw an inchoate “peace dividend,” military programs can be retooled for peacetime purposes, furthering efforts to confront climate change on a national and global scale.

While a threat of China looms, it does not demand a Cold War-era military. Programs like the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter need to be rehauled and cancelled; the overseas contingency operations account — a veritable “slush fund” that has funded endless wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to the amount of $2 trillion since 2001 — can be eliminated (as Biden proposed); many of America’s 800 military bases around the world can be closed; and bi-partisan-led defense acquisition reform can eliminate waste that is endemic to the defense budget. These measures will free up monies for Biden’s domestic agenda and help convert defense programs to climate-sustaining initiatives.

The United States can also counter China’s influence abroad by exercising real leadership in global climate change negotiations. In late April 2021, the Biden administration promised to double its global climate finance efforts by 2024. This comes after a freeze during the Trump administration and is welcome. However, it still leaves the United States behind most other rich nations like France, Germany, Norway, and Britain. Biden’s Earth Day announcement promised to “make good” on President Obama’s promise of $3 billion in climate financing for the Green Climate Fund, but his $1.2 billion pledge still falls short of the $2 billion it owed at the end of the Obama administration.

The rest of the Biden administration’s money for developing country climate finance will be channeled through the State Department’s Development Finance Corporation, rather than the GCF. The distinction is important. From the U.S. perspective, channeling aid through the unilateral DFC over the multilateral GCF is a way to ensure accountability. All too often, however, this kind of aid politicizes and perverts development through subjecting it to Washington’s foreign policy priority du jour.

Biden is right to stress that investing in U.S. infrastructure and workers will make us more competitive with China, as Eisenhower did with the Soviets. But the United States need not adopt the zero-sum rhetoric of the Cold War. As Sen. Bernie Sanders recently argued, we should invest in American infrastructure “because it will better serve the needs of the American people.” Americans are clamoring for government to play a larger role in rebuilding the economy and providing relief. They also want to end, or avoid, endless wars — both “cold” and “hot.” We now face a moment in which transforming how the United States views the relationship between defense spending and social welfare is possible. The Biden administration can and must take advantage.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org