There are multiple reasons why the Biden administration’s plan to hold a “summit for democracy” is a terrible idea that should be discreetly shelved; but several of them can be summed up in just two words: Narendra Modi.

Not inviting India’s prime minister would demolish the apparent purpose of the summit, which is to build an ideological front against “Chinese authoritarianism.” A summit without Modi would not only offend his government, but also many Indians would see it as a grave national insult.

To invite Modi, however, and not talk publicly about his government’s authoritarian-like record would reduce the summit to a farce. This is a man who, until he became prime minister, was banned from entering the United States for nine years because of his alleged role in inciting communal riots in Gujarat in which at least 1,000 local Muslims were killed.

In power, the Modi government has discriminated against Muslims and demolished the secular foundations of Indian democracy, replacing it with a Hindu state in which non-Hindus are at best tolerated. Critics have been imprisoned indefinitely without bail, even as COVID rages through Indian prisons.

Modi’s political origins and power base lie in the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, or RSS, a movement with fascistic characteristics and antecedents. His allies have engaged in hate-filled language and open incitements to violence against Muslims. Under his government, India’s rating by Freedom House has dropped to “partly free” — despite Freedom House’s well-known tendency to adjust its ratings in accordance with Washington’s geopolitical agendas.

His presence would be bitterly unpopular in the Muslim world and hinder U.S. attempts to focus world Muslim attention on China’s repression of its Uighur Muslim minority. To invite Modi would allow every rival of the United States — and many friends — to repeat the accusation that Washington only uses the language of democracy as a cynical tool to advance its interests and undermine rival states, while consistently ignoring the crimes of its own allies.

Moreover, to invite Modi would compel Washington to invite all the other South Asian leaders as well, since they all govern what are, formally speaking, democratic states. They would see being left out as an American endorsement of Indian hegemony in South Asia and would push them, and their populations towards alignment with China — hardly a U.S. motivation for the summit.

And what of the “democracies” of Africa and Central America?

As with Modi, such invitations would hardly enhance the global prestige of democracy. On the contrary, it would only encourage hostile critics to draw attention to — depending on the particular case — rigged elections, extrajudicial executions, imprisonment of dissidents, repression of the media, manipulation of the courts, attacks on opposition parties, brutal suppression of insurgencies, ethno-religious chauvinism, sponsorship of terrorism, and deep systemic corruption of these “democracies.”

As South Asia demonstrates, the line between dictatorships and democracies in the world today is often very blurred. More illiberal democracies in the world today — including Hungary, Poland, and very likely more EU and NATO members in future — may differ clearly from China. But when it comes to issues like the rule of law, human rights, and freedom of speech, their differences with Putin’s Russia are ones of degree rather than kind, and of capability rather than intention.

Thus, for example, the rules that Modi’s government has introduced to restrict the role of foreign NGOs resemble very closely indeed those implemented by Putin in Russia . Also, as we have seen again and again in modern history and can see in many countries today, it is entirely possible for ethnic and ethno-religious chauvinist movements to be elected to power by large popular majorities.

Recent events in India have created a powerful additional argument against the inclusion of Modi in a summit of democracies: criminal negligence, coupled with retrograde superstition. His government allowed the huge Hindu religious festival of Kumbh Mela, which played such a catastrophic role in spreading COVID-19 infection, to be brought forward by a year — into the middle of the pandemic — for astrological reasons. His government has also engaged in systematic suppression of information about the pandemic (including the use of the police and courts to suppress accurate reporting of the death rate) that appears on the surface to cast Chinese efforts in this line into the shade.

The Chinese regime’s association of democracy in general with incompetence and paralysis is not true. The East Asian democracies of Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea have all performed magnificently in combating the coronavirus — but that does not make that association any the less effective as anti-democratic propaganda.

The arguments against a “summit for democracy,” however, go far beyond the cases of India and South Asia. It would also recast America’s own imagination of the world in terms of the old black-and-white Cold War paradigms of good against evil. America’s own establishment commentators themselves would be ensnared yet again in a web of lies and self-deceit about America’s leadership of the “Free World,” of the kind that disfigured and befuddled the U.S. media’s approach to many issues during the Cold War.

In Europe, the United States was indeed generally a leader and defender of liberal democracies against totalitarianism. But that was only true in Europe. Not a single person of my acquaintance in the Arab Middle East — including ones deeply desirous of alliance with the United States — believes that America is or ever was sincerely committed to spreading democracy in the region. Yet the American belief that the United States was sincere and that Arabs and Iranians should trust America helped to lure many liberal American intellectuals into advocating the catastrophic invasion of Iraq.

The great majority of countries in Asia do not want to be forced into a Cold War-style choice between the United States and China, and Washington should do nothing to force this choice upon them. A small but nonetheless significant example: if Pakistan were invited to a “summit for democracy” that was openly staged as an anti-Chinese propaganda exercise, then its own links to China (created out of fear of India, not from any ideological alignment) would probably compel it to refuse the invitation, leading to further and quite unnecessary damage to Pakistan’s links with the West.

Above all, the imagination of the world in terms of good pro-American democracies and evil anti-American dictatorships will reinvigorate the Manichaean worldview that has always lurked not far beneath the surface of American culture and that has led to so many disasters: from the identification of Mossadeq and Ho Chi Minh as agents of global communism rather than anti-colonial nationalists, to the Bush administration’s lumping together of North Korea and mutually hostile Arab nationalists, Iranian Shia and Sunni Islamist extremists in one “Axis of Evil.”

As Charles Kupchan has written, it will be very hard for the Biden administration to cooperate pragmatically and successfully with China and Russia on issues like climate change — as it apparently wishes to do — while on the other hand promoting a view that the world is rigidly divided into democracies and dictatorships, that only democracies enjoy truly legitimate interests, and that the existing Russian and Chinese political orders must be destroyed.

As the great American historian Richard Hofstadter wrote of U.S. attitudes during the Cold War:

“Since what is at stake is always a conflict between good and evil, the quality needed is not a willingness to compromise but the will to fight things out to the finish. Nothing but total victory will do. Since the enemy is thought of as being totally evil and utterly unappeasable, he must be totally eliminated… This demand for unqualified victories leads to the formulation of hopelessly demanding and unrealistic goals, and since these goals are not even remotely attainable, failure constantly heightens the paranoid’s frustration."

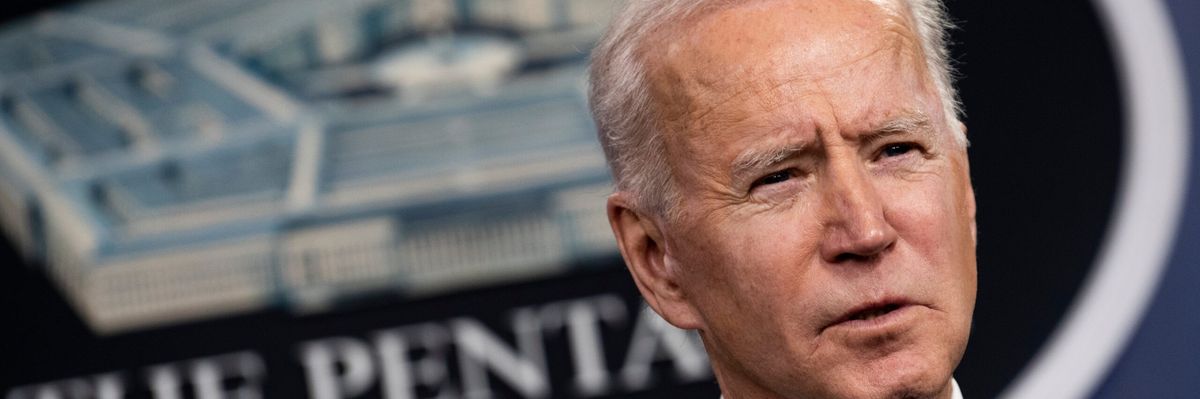

Insofar as the plan for a “summit for democracy” contributes to this kind of attitude, it is a threat to the world and to America’s interests in the world. President Biden’s campaign statement on democracy began by talking about America leading by example and reinvigorating its own democracy. Far better to stick with that, and let the “summit for democracy” quietly fade away.