Professor Jerome Slater set himself an ambitious goal for his new book, “Mythologies Without End: The U.S., Israel, and the Arab-Israeli Conflict, 1917-2020” to address the mountain of misinformation about the conflicts related to Israel’s creation and the dispossession of the Palestinians over more than a century.

Slater writes that he took this on not only “for the sake of historical truth, but also because the conflict is unlikely to be settled as long as the mythologies continue to prevail in Israel and the United States.” The “mythologies” Slater refers to abound, beginning in ancient times, and continuing throughout early Zionist settlement, through numerous wars, to this day, remaining decisive factors in policy in the region and in Washington.

Slater focuses on views that sustain Israeli and U.S. policies and feed the primary myth: that Israel and the United States have sought peace but have been stymied by Palestinian and broader Arab rejectionism. In fact, Slater contends, “it is Israel, not the Arabs, which has ‘never missed an opportunity to miss an opportunity.’ Unwilling to make territorial, symbolic, or other compromises, Israel has not merely missed but sometimes even deliberately sabotaged repeated opportunities for peace with the Arab states and the Palestinians.”

Slater is not the first to make this argument, but his book compiles many arguments that expose this historical truth into one volume. But it is more than a mere polemical compilation of the arguments of others.

Slater analyzes the history of the conflict methodically, exposing one myth after another through dual lenses of ethical judgements and his essential sympathy for both the plight of the Palestinians and historical Jewish suffering. The message that comes across from that dual emphasis is that the Jews have a right and reason to seek remedy, but that the way they have sought it — by dispossessing the Palestinians — is not justifiable.

One of the first ethical questions Slater raises is the right by which Great Britain and the League of Nations decided on the boundaries of Palestine and the right of the Zionist movement to a “national home” there. By teasing out the ethics of this question and others throughout the history of the conflict, rather than treating them as axiomatic, Slater welcomes the reader to wrestle with the morality of the historical record, rather than either side’s national narrative.

Looking at the League of Nations’ Mandate and Britain’s Balfour Declaration, Slater states that both “had no more legal or moral standing than any other colonialist actions.” The implication, however, is that lacking moral or legal justification, they still had an enormous political impact. Slater doesn’t allow the reader to simply take that as given, that the powerful once again had their way over the powerless. Instead, he considers the century that has passed since those colonialist actions in the context of that illegitimacy.

This perspective infuses Slater’s work with a fresh approach to some of the more familiar myths he smashes. The matter of Palestinian “transfer” during Israel’s initial creation from 1947-49, for example, has been rehashed and debated fiercely since the events took place. Despite scholarship that has been widely known since the late 1980s — and was based on histories, including Palestinian ones, that pre-dated it — the myth of Palestinian flight caused by calls to evacuate so the Jews could be “driven into the sea” persists.

Slater reviews and consolidates that scholarship into a powerful case for the planned transfer that had been a goal of most Zionist leaders since the early days of Jewish immigration to Palestine. Here, however, Slater’s view that the Holocaust was the final straw in the case that the Jews needed a state runs up here against his equally firm conclusion that the expulsion of some 750,000 Palestinians was a massive injustice.

Slater attempts to untangle this moral morass by suggesting that, had the Israeli leadership truly been interested in establishing a Jewish state with as little harm to the Palestinians as possible, they could have offered compensation for Palestinians’ voluntary departure. This, in his view, would have brought the population in the new Jewish state much closer to the 80 percent Jewish majority that Ben-Gurion felt was necessary, and if expulsion of any more people was then necessary, it would have been a terrible injustice, but on a much smaller scale than what actually took place.

Slater’s attempt to balance a strong nationalist and political drive with ethical concerns is sure to make pragmatists question the likelihood of a superior force going to such expense and difficulty, especially during an ongoing conflict, to address the human rights of the enemy. And it will leave ethicists completely unsatisfied with his conclusion.

Ultimately, though, what Slater is trying to do is break the prevailing myths, and demonstrate that other outcomes have been, and remain, possible if there is a genuine effort to find an accommodation. He makes a persuasive case that it is Israel and the United States, not the Palestinians and Arab states, that fail on that score.

Slater reviews the evidence that Egypt was trying to avoid war in 1967, albeit not always in the most effective manner, and he demonstrates that the Soviet Union, while certainly pursuing its own interests in the region, was much more inclined than the United States and Israel toward compromise. By bringing a range of specific arguments together about the Cold War era history of the region, Slater builds a clear picture of the relative roles of the Soviets and Arab nationalism, both of which, he establishes, have been mischaracterized in mythologized history.

Slater notes that the Arab Peace Initiative of 2002 — which Israel ignored for years — was actually based on Saudi initiatives as far back as 1975 and which were refined again in 1981. The offer was “a threat to Israel’s very existence,” according to future Prime Minister Shimon Peres in 1981. This incident is typical of the many missed opportunities that Slater chronicles.

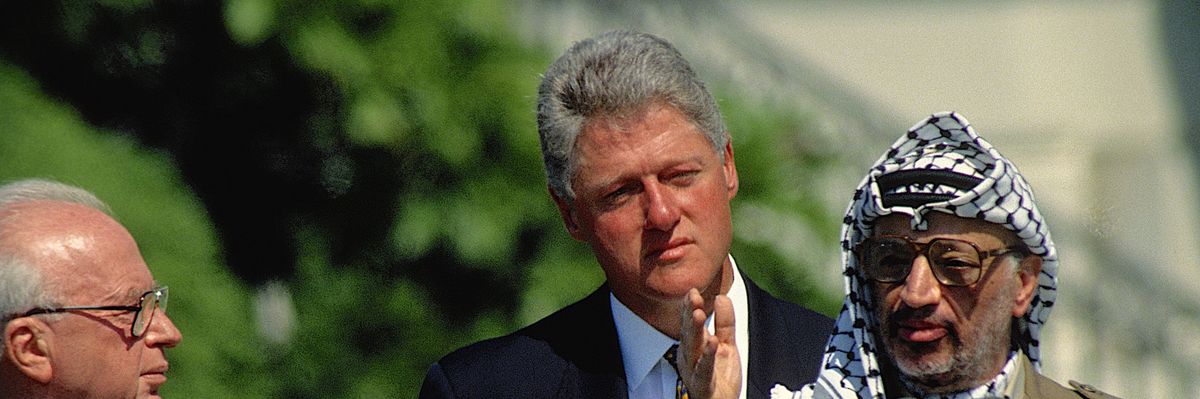

From Bill Clinton’s broken promise to Yasir Arafat that the latter would not be blamed if the Camp David talks of 2000 failed, to Hamas’s evolving policies, to Ehud Olmert’s rapid expansion of settlements even while he was proposing peace to Mahmoud Abbas, all the way to Donald Trump’s threadbare “Deal of the Century,” Slater explodes myths both well-known and obscure in this book.

If Slater can be faulted in his examination it is in relying too heavily on the Palestinian Authority and PLO leadership and ignoring the gap between their promises, especially on refugees, and the popular sentiment among Palestinians, which sees the right of return as sacrosanct. His reliance on the Palestinian leadership’s assurances that they can essentially forego implementation of that right is dubious, and is contested by many Palestinian activists, in and out of the Palestinian territories.

That view, and his justifiably bleak analysis of the political landscape led Slater to conclude that the best way forward would be for Palestinians to accept what they can still get from Israel and the United States in the form of what he calls a “mini-state” along the lines of Luxembourg. It is not a convincing prescription.

Still, this doesn’t impact the core of Slater’s argument. Slater makes a strong case that a real desire for resolution on the part of the United States and Israel could have changed the course of history, and that shifting policies even at this late date toward more productive ones could still resolve this vexing conflict.