Since 9/11, the United States has increasingly come to rely on foreign allies and partners to accomplish shared security objectives and sometimes even fight on its behalf. At the same time, while Congress has abdicated much of its responsibility for national security oversight to the executive branch, my new report, Managing U.S. Security Partnerships: A Toolkit for Congress, shows that Congress has a number of tools it can use to hold U.S. security partners accountable and end U.S. involvement in wars from Afghanistan to Yemen.

Members of Congress have begun to rediscover these tools in recent years, using them to create a growing role for Congress in ending America’s “endless wars.” In 2019, Congress passed legislation to invoke the War Powers Act to end U.S. support for the Saudi-led coalition intervention in Yemen and to limit arms sales to Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. In 2020, Congress again invoked the War Powers Act, this time to block the administration from using force against Iran without congressional authorization.

Using these tools is rarely as simple as passing a piece of legislation with a veto-proof majority. Rather, Congress can use its authorities — including the power of the purse and its role in the arms sales process — to increase transparency around often complex and opaque security partnerships, negotiate policy with the executive branch, and to place direct pressure on security partners.

The recent batch of legislation around Yemen’s war is a good example: while President Trump vetoed the bills invoking the War Powers Act and blocking arms sales, pressure from Congress contributed to the signing of the Stockholm Agreement between parties to the Yemen war in December 2018 (providing an opening for peace negotiations) and to the Emirates’ decision to withdraw most of its forces from Yemen in 2019.

Regardless of who wins the upcoming presidential election, Congress can and should use these tools at its disposal to limit U.S. involvement in conflicts around the world.

Increase transparency around security assistance programs

One clear avenue for congressional influence is through its responsibility for funding security assistance programs that provide U.S. military training, advising, and equipment to partner militaries. The United States operated 167 of these security aid programs with a total of $18.81 billion in funding in 2019, according to Security Assistance Monitor, and 20 military training programs in 137 countries. These programs have grown rapidly in the wake of 9/11, with funding for security assistance more than doubling since then.

Despite this rapid expansion, U.S. security assistance programs have become what Andrew Miller, Deputy Director for Policy at the Project on Middle East Democracy, and Daniel Mahanty, director of the U.S. program at the Center for Civilians in Conflict, have called “faith-based programs” — despite the fact that security assistance has become a default foreign policy option, there has been little effort to define the objectives of this assistance, let alone to measure its effectiveness.

Congress can increase transparency around security assistance programs by writing “reporting requirements” into relevant legislation, such as the National Defense Authorization Act, which is often a vehicle for such legislation because it is considered a “must-pass.” Reporting requirements direct the relevant agency, such as the State Department or the Pentagon, to submit reports to Congress, providing Congress and the public with important information on these programs.

Congress could also require that implementing agencies clearly lay out program aims and metrics of effectiveness. Congress could also include funding in each program’s budget for evaluation and monitoring tied to these metrics. To take one example of how this works in practice: the Fiscal Year 2016 NDAA included a requirement that the Defense Department must establish a monitoring and evaluation framework for security assistance; DoD released its Instruction on Monitoring and Evaluation the following year. While these requirements fall short by some measures, they are a useful first step towards subjecting security assistance to scrutiny.

Negotiate and vote to block problematic arms sales

The 1976 Arms Export Control Act requires that Congress is notified of arms sales to foreign militaries over a certain dollar threshold. The way the law works today, a weapons sale proceeds unless Congress can cobble together a veto-proof majority to block it via a joint resolution of disapproval, explaining why Congress has never been able to successfully block a sale this way (although it has come close).

Nevertheless, the terms of the AECA gives Congress substantial, if subtle, leverage over arms sales. The AECA requires that the administration provide a formal notification to Congress at least 30 calendar days before the contract is finalized. However, before providing formal notification, the State Department has historically submitted an informal notification to the chair and ranking member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and House Foreign Affairs Committee, which have jurisdiction over arms sales. Then, their staff review the sale and may ask for additional information and may negotiate with the State Department to add conditions or restrictions to a contract.

While this informal process is not legally required, administrations do it in large part because it ensures that the sale is more likely to pass through Congress without a public airing of concerns that could tank the sale. It gives Congress leeway to shape arms sales in a way that is not necessarily publicly visible.

When Congress and the administration fail to reach an agreement this way, Congress can vote to block arms sales via a joint resolution of disapproval. While the bar for successful passage of this legislation is high, this type of legislation is privileged, meaning that it is more likely to get an expeditious floor debate and a vote. Holding a vote to block problematic arms sales can therefore provide a focal point for building public attention and can serve as leverage to change the behavior of the recipient country, even if the legislation does not ultimately become law.

Can this approach work?

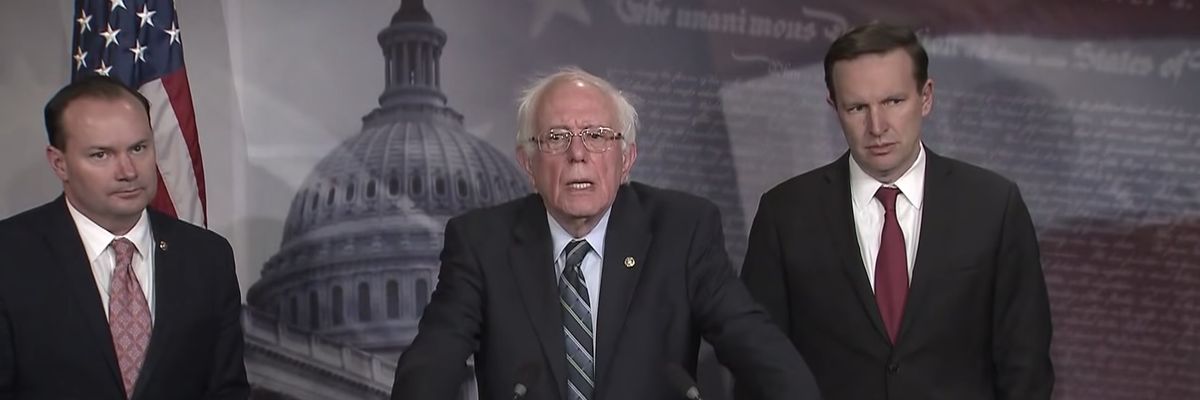

In this deeply polarized political environment, it is hard to imagine Congress getting much done, let alone on a bipartisan basis. But Congress is well-placed to expand its role in ending endless wars using these tools in part because there is genuine bipartisan support for them in Congress. Progressives like Senator Bernie Sanders and Congressman Ro Khanna and conservatives like Senators Rand Paul, Todd Young, and Mike Lee have supported legislation to block arms sales, for example. And even when members of Congress support the status quo on U.S. security relationships, many nevertheless insist that the executive must respect Congress’s oversight role. At a July 2019 hearing, Senator Ted Cruz castigated the Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs for the administration’s attempt to cut Congress out of the arms sales review process, warning that they need to “follow the damn law and respect it.”

With bipartisan support for congressional oversight, Congress can play a critical role in drawing down U.S. engagement in endless wars.