Influential powers have always aimed at mediating critical conflicts while furthering their national interests. U.S. President Donald Trump’s recent offer to mediate the current India-China border confrontation high in the Himalayas is no different. In May 2020, as tensions between India and China heightened, Trump tweeted that Washington was “ready, willing and able” to arbitrate between the two countries. On September 24, during a press conference, he reiterated his offer, stating that the Asian giants were “having difficulty, and very — very substantial difficulty.” Both New Delhi and Beijing, however, have clearly rejected the offer, emphasising that the conflict is a bilateral one and a sovereign issue in which third-power involvement is not welcome. But there are several additional factors driving their refusal to accept Washington as a mediator.

First of all, China — and even India — perceives any U.S. interference through a hegemonic lens, dictating terms with its “old-style” foreign policy approach that often overshadows the goodwill gesture itself. Beijing views U.S.’s involvement via the prism of a ‘Thucydides Trap, given its multifaceted relations with Washington. China has been increasingly decrying U.S.’s inclusion in the Asia-Pacific, with its state-sponsored news outlet Global Times regularly referring to Washington’s “interference,” its “desperate” attempts to “start trouble” and cause problems for its “regional allies.” This is especially true with reference to China’s territorial and maritime disputes with its neighbors in the East China Sea, South China Sea, and with India.

Beijing essentially sees Washington as “anti-China,” determined to curb the China’s rightful return to its past glory, under President Xi Jinping's “Chinese Dream” narrative. Trump’s branding of the coronavirus as the “Chinese virus” has only added to worsening bilateral ties. U.S. humanitarian support to the Tibetan cause and military and political support to Taiwan, are two extremely sensitive issues for Beijing, deeply concerning for China as they undermine the “One China” policy. In the Tibetan context, which is closely linked to the India-China border dispute, Beijing is eagerly looking at a different situational trajectory under the next Dalai Lama; thus any U.S. interference, even in a mediating role, presents too many risks and could seriously jeopardize Chinese interests.

Both Beijing and New Delhi are also probably mindful of the U.S.’s history in the Himalayan region. The Central Intelligence Agency’s propaganda and separatist operations in the Tibet Autonomous Region, or TAR have been a source of Beijing’s deep-rooted distrust of Washington. In the 1960s, the CIA trained and armed a guerrilla fighting force that resisted the PRC’s Communist rule. The CIA’s Tibet program, known as “Mustang,” gathered important intelligence that was shared with India during the 1962 Sino-Indian war. In fact, the CIA worked with Indian intelligence to train an elite, off-the-books Indian Army unit in mountain warfare, composed of Tibetan rebels of the same guerrilla force. Nicknamed “Establishment 22,” the Special Frontier Force has reportedly been planned for use as a countermeasure in the ongoing conflict. With this complex and sensitive history looming over the Sino-Indian border dispute, any U.S. involvement would necessarily complicate the situation further.

Meanwhile, India too realizes that while Washington has expressed hope for resolving the conflict, escalation will work in favor of Trump’s anti-China policy. Trump’s offer appears appealing, considering that Washington would tilt the negotiating process in India’s favor. However, if India were to invite U.S. participation, China would view it as an unacceptable escalation and construe it as New Delhi’s concrete alignment, if not alliance, with Washington. Consequently, it would only stall talks further and attract more hostility from Beijing.

Despite the current border tensions and domestic anti-China economic measures, such as banning Chinese apps, India has been cautious to avoid appearing overtly anti-China, choosing instead to manage and mitigate the “China problem” that arises so often. India’s External Affairs Minister Dr. S. Jaishankar wished China on October 1 a congratulations for the anniversary of the PRC’s establishment. Amid the ongoing border tension this indicates the importance of the Sino-Indian relationship even post-Galwan. India’s power-partner parity configuration with China under the aegis of “developmental partnership” still seems to be a relevant way forward, as such a narrative allows India to face China as both a “disruptive power” in the Indo-Pacific and a “prudent economic partner” in the multilateral domain.

Besides, while the Galwan clash may have hastened India’s cooperation with its Indo-Pacific partners and made it more assertive in its security partnerships with “like-minded” countries, an outright alliance with any particular bloc is still not a part of India’s foreign policy strategy. India is instead pursuing a “pointed alignment” tactic to expand its security and military ties selectively. In fact, Jaishankar recently confirmed that India would “never be part of an alliance system.” Further, New Delhi is distinctly aware that as Washington’s global clout shrinks amid the new geopolitical realities, India must remain practical while staying vigilant towards any Chinese aggression. Hence, a stronger military-centric alignment, rather than an alliance, with the United States would serve India’s interest more.

At the same time, it is worth noting that for the United States, it appears that containing China is an utmost priority — and an alliance with India vital to fulfilling this interest. Closer alignment with New Delhi could help Washington strengthen its Indo-Pacific ambitions, particularly as it readies itself for what might very well evolve into a new and drawn-out cold war with China, no matter who occupies the White House after the November election.

For New Delhi, however, the presence of American troops and military bases within its borders, along with deeper defense trade – essentials of what constitutes an alliance — remains unacceptable. Not only would such an alliance completely break from the non-alignment principle guiding Indian diplomacy in its post-colonial era, it would also work against its current national interests by giving foreign forces a say in its often-contested international affairs, especially with its neighbors. It would dilute India’s independence and its capacity to be an able security provider for its immediate neighborhood. With India’s long-standing bid for United Nations Security Council permanent membership in tow, New Delhi would not want to come across as a country needing the help of a permanent UNSC power to handle a “sovereign” dispute with another permanent UNSC power.

Furthermore, India and China have been accommodating each other’s interests on certain international issues or in multilateral domains. One such common goal is the reformation of the Bretton Woods institutions and greater Asian representation on the global stage, even though such exercises have taken a backseat of late. While China is a revolutionary revisionist power, India too displays characteristics of being an emerging, evolutionary, revisionist nation. In this context, U.S. mediation could, to an extent, reinforce Washington’s standing as a “superpower” at a time when India and China are both aspiring to mold a new global order — China’s vision being a world shaped by Xi Jinping’s socialist thought and India conceptualizing a multi-polar Asia and international order.

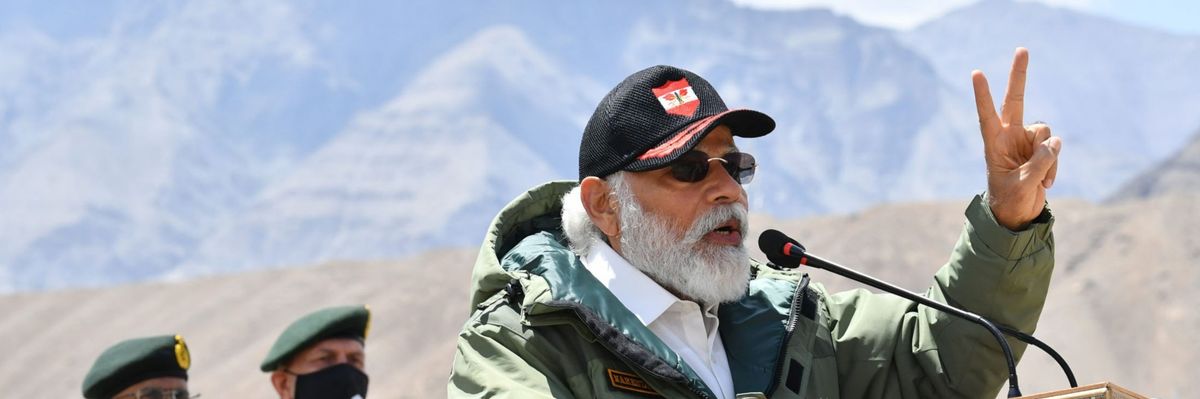

In addition, Washington’s mediatory role is ever-more complicated by the current leaders at the helm: Xi, Modi, and Trump all have nationalistic outlooks and are dependent on nationalism-driven domestic support. The three leaders are unlikely to agree on any move that could be perceived as “weakness” in their leadership. For Xi and Trump, in particular, any appearance of bowing to the other, especially under rising anti-U.S. and anti-China sentiments within their respective nations, would only prompt public outrage. Both India and China are also mindful of the forthcoming U.S. election, which might bring Democratic presidential nominee Joe Biden to the White House, and uncertainty about the extent to which he will follow Trump’s proposition for mediation.

All in all, U.S. mediation in the India-China boundary dispute would have largely detrimental consequences for both parties. Beyond reasons that stem from claims of resolving sovereign disputes bilaterally, the unlikelihood of easy compromises from either of the three leaders, the changing geopolitical order, and growing domestic economic and political concerns in all three countries render any third-party mediation between the two Asian giants highly unlikely — let alone by the United States.