In a recent piece for Responsible Statecraft, Gregory Kulacki argued that China is unlikely to engage in a nuclear arms race with the United States and, in short, that Washington is wrong to regard the country as a nuclear problem. The odds of China engaging in nuclear competition with the United States are indeed slim, but that isn’t what concerns Washington. The source of Washington’s problem with Beijing is elsewhere.

Let me begin with this. Kulacki is right that China only has a few hundred nuclear warheads, whereas the United States and Russia have several thousand. He’s right that there are reasons to be skeptical about reports suggesting that China may double the size of its stockpile by the late 2020s; U.S. forecasts have often overestimated China’s arsenal growth. Kulacki is also right that China has chosen to build a small arsenal, despite having the means to build a big one, and he’s right that the United States largely has failed to understand Chinese nuclear thinking.

Since it exploded its first nuclear device in 1964, China has had a strategy of assured retaliation and hasn’t integrated nuclear strategy with conventional strategy or pursued nuclear warfighting, even limited. That’s why Chinese leaders have maintained tight control over their arsenal ¾ they never delegated its authority to the People’s Liberation Army — and opted for a de-mated force and no-first-use policy.

That doesn’t mean, however, that the United States is wrong to worry about China. Yes, China has a smaller arsenal than the United States and Russia, but it is bigger than any of the other nuclear-armed states, it is growing, and Beijing refuses to articulate a level at which it would have “enough” weapons. China is also the only country of the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council that leaves open the possibility of producing more fissile material for explosive purposes, and it has rejected transparency measures on its capabilities of the kind adopted by the other permanent members.

Moreover, China has been modernizing and expanding its delivery systems rapidly. Its land-based force now includes numerous mobile, solid-fueled missiles of intercontinental and intermediate range; unlike the United States and Russia, China has been free to develop intermediate-range missiles because the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty only bans U.S. and Russian land-based systems of that range. Beijing has also developed penetrative aids, multiple independent reentry vehicles, and hypersonic glide vehicle technology, and it is bringing online sea and air nuclear platforms, entering the exclusive club of nuclear-armed states possessing a triad.

Beijing has argued that these developments are defensive, that China’s nuclear strategy and no-first use policy remain intact, and that modernization is consistent with its tradition of minimum deterrence. Plainly, Beijing has said that its goal has been to ensure the reliability and survivability of its arsenal, especially in the context of improving U.S. missile defenses and strike capabilities, and the U.S. refocus on Asia, which Beijing regards as an attempt to contain China.

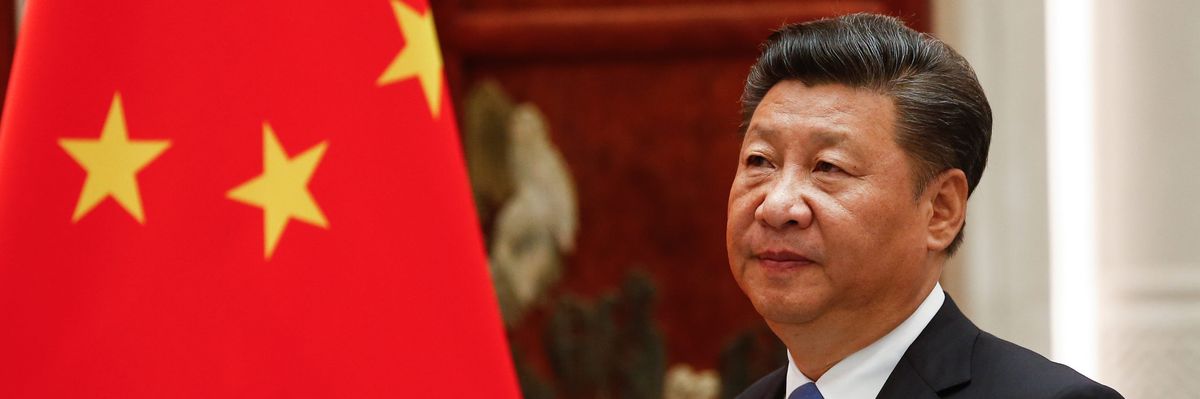

Yet, from a U.S. perspective, Chinese developments are concerning because they raise questions about Beijing’s intent, particularly given how much China has changed since Xi Jinping took office in 2012. In a few years, China has become increasingly repressive at home and assertive abroad.

What concerns the United States exactly? Three areas stand out: strategic equivalency, nuclear change, and inadvertent escalation.

Strategic equivalency: Years ago, Washington worried about a Chinese “sprint” to nuclear parity, a concern first articulated under the George W. Bush Administration. That concern has not disappeared, partly because it is occasionally fueled by the Chinese media. It is no longer dominant, however, because U.S. officials have realized that China is far behind the United States and seemingly unwilling to go down that path. Today, Washington fears primarily Beijing’s success in achieving what one analyst has labeled “strategic equivalency”: growing strength in and across multiple domains — conventional, space, cyber, and others besides nuclear — allowing China to become competitive at lower ends of the conflict spectrum and potentially win wars. Scholarship shows that Beijing has developed concepts and capabilities to seize territory quickly, establish a fait accompli, and, if necessary, counter a U.S. response while staying below the nuclear threshold.

Nuclear change: Washington is also concerned that the evolution of China’s nuclear capabilities could present Beijing with new options. Beijing could adopt a launch-on-warning, or LOW posture, abandoning China’s traditional stance to retaliate only after it has absorbed a nuclear strike. The improved mobility, readiness, and informatization of assets and the PLA’s space-based early warning system make adoption of such a posture possible. So does the emerging nuclear role of the PLA Navy, given that nuclear warheads have to be mated with delivery systems on sea platforms. A LOW posture would be incompatible with a no-first use policy, especially because Beijing has repeatedly pointed to its de-mated posture as evidence that it abides by no-first use principles. There is no evidence that Beijing has adopted a LOW posture, let alone a nuclear warfighting option, but some analysts have stressed that China’s nuclear forces may be given a new, more expansive role with the military reforms initiated in 2015. Discussions in unofficial dialogues also suggest that Chinese strategists are well-aware that modernization looms large on China’s policy and strategy and that some change may be unavoidable.

Inadvertent escalation: Finally, Washington worries about the risk of inadvertent escalation with Beijing, which could have many sources. One could result from the growing Chinese role in and across multiple domains, where moves in one domain could trigger responses in another and lead to war — and nuclear use. Another could stem from China’s commingling and co-location of its nuclear and conventional assets, and the possibility that in a crisis U.S. attacks on China’s conventional forces trigger a Chinese nuclear response; Beijing has long had a “dual deterrence” doctrine, but it has only begun fielding numerous dual systems recently, and it is now doing so on multiple platforms, magnifying the risks. A third source of potential inadvertent escalation could emerge from the lack of clarity about what Beijing views as its “core interests” and what Washington considers the “vital interests” of the United States and its allies.

Accordingly, the United States has legitimate concerns with China, and these concerns extend beyond nuclear weapons. Washington’s push to jump-start a dialogue with Beijing, therefore, is laudable, and a goal which predates the current administration.

Given that Beijing has systematically declined participation, the question for Washington is how to reverse the trend. While it is possible to conceptualize what a U.S.-Russia-China trilateral arms-control agreement — the current stated US objective — could look like, concluding such an agreement is unlikely to happen before extensive bilateral work. Regardless of the engagement format, Washington needs to convince Beijing that it is Chinese interests, i.e., that China would gain, or at least not lose, something by participating.

Attempts to publicly shame Beijing into entering talks or to appeal to its great-power status are unlikely to work, even though it is appropriate to — perhaps privately — counter the argument that China is too weak to engage. Similarly, while the United States should adapt its deterrence posture to account for Chinese developments, threatening an arms race is unlikely to be productive.

A decisive move would be for Washington to publicly acknowledge what has long been the case, and the primary sticking point for Beijing: that China has a credible deterrent and that the United States and China are mutually vulnerable. That, more than anything else, could trigger engagement, giving Washington an opportunity to address its concerns with Beijing, and vice versa.