The internal war and outside intervention in Yemen appear to go on unabated under the neglectful eye of the Arab world and the international community. The recent armed struggle for Socotra has left the Southern Transitional Council (STC), supported by the United Arab Emirates, in charge of the island. A UNESCO-declared world heritage site, Socotra has been trampled by troops, armored trucks, and tanks, much to the detriment of its fragile ecosystem and historically peaceful population. Battles continue to rage just east of Aden, where STC fighters remain in a stand-off with troops loyal to President Abdrabbuh Mansour Hadi’s government for control of neighboring Abyan province—as part of the overall struggle for the entire south of Yemen. Farther north of Abyan, Houthi/Ansarullah troops are pursuing a months-long attempt to enter the capital of Marib and secure all oil and gas facilities there. To the west of Marib, a tense front still exists around the city of Hodeida, a strategic port for the importation of humanitarian assistance and potential export of oil via the Red Sea.

Of course, all this is aside from the main war between Saudi Arabia and the Houthis, which is being conducted by air, land forces, and rocketry over the capital Sanaa, the Houthis’ capital Saadah, and Saudi Arabia’s southern border at al-Jawf governorate. Added to that complex geopolitical picture is a pandemic that is sweeping over all without distinction as to party or regional affiliation. Indeed, there is a clear and full tragedy unfolding in Yemen.

Enter COVID-19

The devastating impact of war, disease, and poverty on the people of Yemen has been compounded by a now widespread epidemic for which the country was ill-prepared. At first, COVID-19 looked like it had somehow spared the country as one Middle Eastern country after another fell prey to the virus in early March. Although lacking reliable information from Yemen itself, international agencies now report that virus-related deaths have very likely exceeded the death toll from the war raging in the country since 2015.

Although lacking reliable information from Yemen itself, international agencies now report that virus-related deaths have very likely exceeded the death toll from the war raging in the country since 2015.

The alarming spread of COVID-19 in Yemen is cause to seriously doubt the sincerity—and even the sanity—of those who pursue victory through war instead of negotiations. This critique includes all sides to the conflict as they continue to give priority to improving their strategic positions on the ground. Numbers vary widely depending on the source of information, but a million infections is not an unreasonable estimate at this point. One thing is certain however: the spread of diseases has overwhelmed the country’s inadequate public health institutions. Instead of dramatically building up Yemen’s capacity and encouraging a coordinated regional and international effort to mitigate the spread of the deadly virus, the Arab coalition fighting the Houthis continues to prosecute the war directly from the air and via proxy forces on the ground. The vast sums being spent on the war primarily by the Arab coalition, if diverted to public health, could save millions of lives currently at risk. The fault, however, belongs to all those trying to fill the void at the center caused by the 2011 revolt, which led to the departure and ultimate demise of the late president, Ali Abdallah Saleh, and his replacement by a weak-to-nonexistent legitimate authority.

Yemeni, Saudi, and Emirati sins

Yemen has fallen into chaos because of the mistakes of an otherwise strong president, the late Ali Abdullah Saleh, who could not find it in himself or his advisors to listen to the protesters and invite them to help transition the country from authoritarianism and corruption into a more democratic and less corrupt system of government. War and chaos also resulted from the Houthi takeover of Sanaa in 2014, reflecting the clumsy efforts of the United Nations and the Gulf Cooperation Council to patch together a new social contract among the various Yemeni factions and regions. None of this was helped with the Saudi-led Arab coalition’s intervention in the country in 2015, ostensibly to repel the Houthi takeover, derail what the Saudis perceived as a growing Iranian menace on their southern border, and restore the internationally recognized government of President Hadi to power. Five years of this war have achieved quite the opposite: the entrenchment of the Houthis in Sanaa, a growing Iranian influence bucking up the Houthis, an increasingly divided country, and a marginalized Hadi government.

Five years of this war have achieved quite the opposite: the entrenchment of the Houthis in Sanaa, a growing Iranian influence bucking up the Houthis, an increasingly divided country, and a marginalized Hadi government.

Whatever the agenda of the Saudi and Emirati leadership, it could not have been pursued without the willing participation of Yemeni militias and armies on the ground. To start with, the Hadi government, living in the lap of luxury courtesy of the Saudi government, has been fighting for a secure foothold inside Yemen and has sought to keep control of Yemen’s central bank holdings. However, it has been unable to do that in either Sanaa (which was taken over by the Houthis) or Aden (where the STC challenges it). Hadi loyalists have been fighting in Marib, trying to fend off Houthi attacks to remain in control of oil and gas facilities in the area. The Hadi forces have also complained of inadequate support from Riyadh, especially because they have to fight on at least two fronts: north with the Houthis and south with the STC and other UAE-supported forces trying to form a separate state there. There are reports of the Saudis’ unhappiness with Hadi’s leadership, that they may be searching for alternatives. Indeed, everyone now questions the Hadi government’s legitimacy as well as the efficacy of continuing to vest this honor upon him when he, like every other major player in Yemen, is struggling to hold on to land and resources.

In fact, the Riyadh Agreement, purportedly a plan to merge the STC with the Hadi government and put an end to bloodshed and chaos in the south, has been suspect in the eyes of Hadi as well as analysts who see it as an abandonment of Hadi in favor of the STC. The hostile takeover of Socotra Island is the most recent example of the STC trying to assert southern independence with clear support from the UAE and suspected connivance from Saudi Arabia. There is no military value to the island for the STC, save that of adding territory to what it already controls in the south, in addition to how the island might help the UAE’s maritime ambitions in the Arabian Sea. It represents, however, a significant defeat for the Hadi government and a further squeezing out of their forces from the south. What is noteworthy here is the withdrawal of the small Saudi force that had gone to the island in 2018 after the UAE sent an expeditionary force, ostensibly to mediate between UAE forces and the island’s population. STC leader Aidarous al-Zubaidi had recently returned from a visit to Riyadh to confer with the Saudi leadership, leading to speculation at the time that the Saudis were lending legitimacy to his desire for an independent southern state.

If the reported Saudi offer of a Riyadh Agreement part II is true, it would shed even more doubt on Saudi intentions and add credibility to reports of their discontinuing support to President Hadi. This offer evidently suggested the STC withdraw its troops from Aden and into Abyan, with no mention of where Hadi’s forces would be deployed. If implemented—and there is no chance of that happening, in any case—it would mean an expansion of STC influence into Abyan, a contested governorate not currently under their control.

Under the best of circumstances and assuming good intentions, Saudi and Emirati leaders are under intensifying pressure to cut their losses in Yemen, given the increasing cost of the war, lower revenue due to the depressed prices of oil, and the vulnerability of their own countries to rocket attacks and land incursions in southern Saudi Arabia. The management of Yemen, as administered territory, also seems too much of a challenge for the Arab coalition, unless one wants to assume the worst and conclude that the prevalent chaos is exactly what they wanted to achieve.

The management of Yemen, as administered territory, also seems too much of a challenge for the Arab coalition, unless one wants to assume the worst and conclude that the prevalent chaos is exactly what they wanted to achieve.

The Houthis, whose motives in capturing Sanaa in 2014 were never transparent, stopped short of taking over Aden due to local resistance and the military intervention by the Arab coalition. They have alternated between trying to hold on to northern territory they control and pushing to expand their area. This lack of transparency has become a hallmark of Houthi rule; most recently, the Houthis were legitimately accused of hoarding information about the spread of COVID-19, brazenly declaring that revealing accurate information on the spread of the disease only causes panic among the population. Information has also been withheld on how they collect and spend their revenue. Specifically, concern has been voiced about widespread corruption within the disbursement of international aid, both by the authorities in Sanaa and by the UN agencies directing and monitoring the process.

The sins of the international community

Since 2011, three successive UN special envoys have failed to stitch together an agreement to reconcile the various parties in conflict and to get the permanent members of the UN Security Council to put their weight behind an effort to end the war. The latest of the envoys, Martin Griffiths, wasted two years trying to secure the neutrality of the vital Hodeida port while the real war raged elsewhere in Yemen and Yemeni and regional parties continued to fundamentally disagree on what a final agreement would look like.

The United States, guilty by association in the launch of the war in 2015, has failed to fully engage its diplomacy in the service of peace, continuing instead to fuel the fighting with huge arms sales, training of fighter-pilots, and putting in place a missile defense system in an extensive but futile effort to guard against rocket attacks against sensitive targets inside Saudi Arabia. Democrats in Congress have repeatedly urged the Trump Administration to suspend arms sales to the region, arguing that peace and stability in Yemen are in the best national security interests of the United States. The latest legislative effort, by Senator Chris Murphy (D-Connecticut), does not seem any more promising than previous attempts—at least while the Republican majority continues to block such moves.

Yemen needs Yemenis

Young men and women from Yemen are now spread far and wide across Europe, the United States, and Asia. Through their various engagements and contributions, they have demonstrated the ability of a new Yemeni generation to launch a rebuilding of their country and lead it into the future. Oil and gas potential is very promising and could well support such efforts once the war ends. If the international community seems incapable or unwilling to stop the bloodletting, it remains incumbent on Yemeni leaders themselves to use the good counsel of their youth to patch up their differences and enable a positive and constructive transition into the future.

This article has been republished with permission from the Arab Center Washington DC.

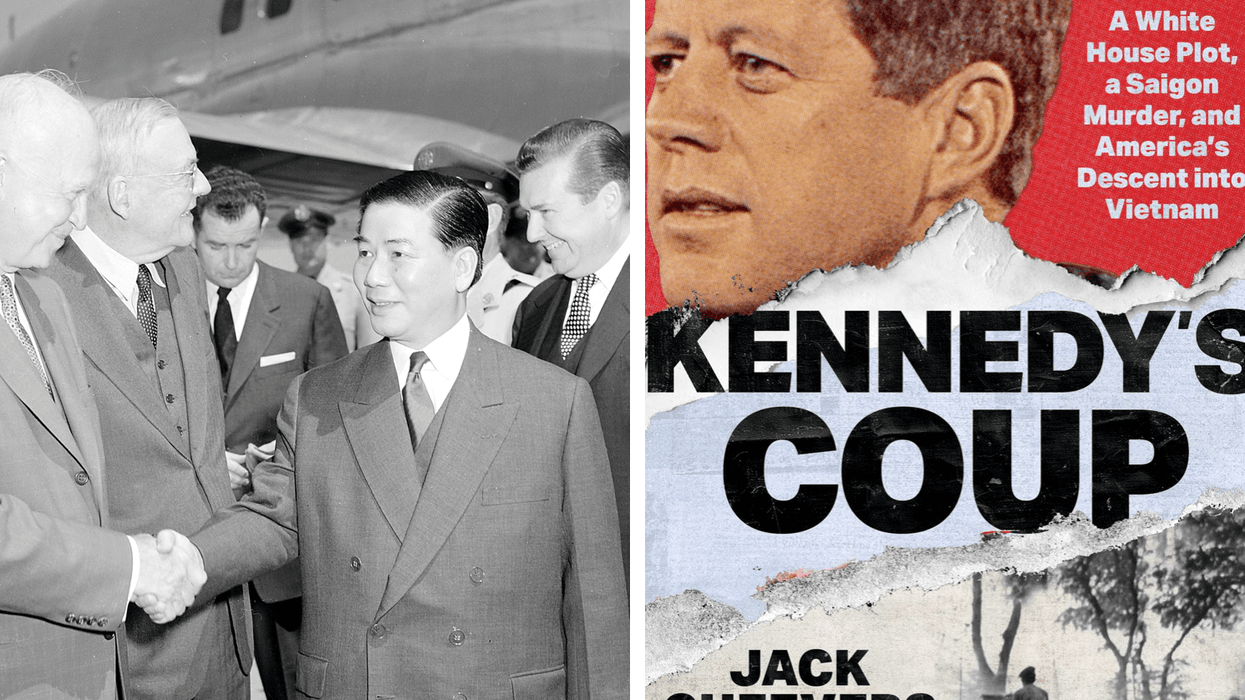

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)