In recent years, the United States and China have experienced increased conflict and tension and diminished cooperation. This has been a costly for both countries, as it has led to greater risk of conflict and forsaken potential gain. Nonetheless, Washington think tank analysts and American nationalists and ideological extremists inside and outside of government continue to advocate for cold war policies that will accelerate the trend toward greater hostility and belligerence.

The United States and China are engaged in transformative power transition with implications for the balance of power in East Asia, contributing to increased strategic competition. The power transition also contributes to trade tension, as it compels U.S. and Chinese reconsideration of the bilateral terms of trade and investment. But the power transition does not preclude constrained security and economic competition nor cooperation on common on bilateral and global interests.

Leadership matters. The trend toward unmitigated conflict is neither inevitable nor irreversible. Pragmatic leadership that focuses on national interests can contribute to constrained conflict and greater cooperation. China shares responsibility for the downturn in relations and it requires leadership that contributes to restrained competition and greater cooperation. But Chinese shortcomings cannot excuse the failures of American foreign policy and the costs to American interests.

Toward U.S. strategic constraint

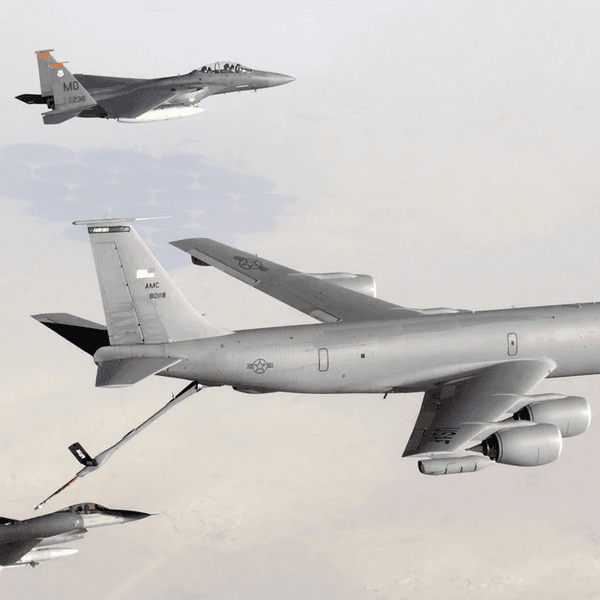

America’s response to the rise of China has been predictable. It resists China’s challenge to the East Asian balance of power. The Trump administration has increased military spending to contend with the Chinese Navy. The U.S. Navy has undertaken a wide-ranging review of its ship-building priorities, it is designing new weapons systems and communications technologies that take advantage of U.S. advances in high technology, and it has increased its challenge to Chinese maritime claims to signal its resolve to defend its security commitments. The United States is also developing security partnerships on the perimeter of East Asia to constrain and contain Chinese naval activities within East Asia’s seas.

Chinese policy has been just as predictable. China never accepted the legitimacy of U.S. maritime hegemony in its coastal waters or American air and naval power projection capabilities deployed on China’s perimeter, including in South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines. Over the last decade it has funded the expansion and modernization of its navy, so that it is both modern and larger than the U.S. fleet. And it has carried out unwavering maritime actions to coerce the region’s secondary powers to constrain security cooperation with the United States.

U.S.-China competition has increased, but the course of the competition will be determined by national leaders, including U.S. leaders. Constrained competition requires U.S. adjustment to the power transition and acknowledgement of Chinese interests in a revised regional security order commensurate with its improved capabilities. U.S. insistence on maintaining the post-World War II status quo will lead to greater Chinese belligerence as China insists on a security order commensurate with the changing balance of power. Singapore Prime Minister Lee Hsien-Loong expressed it well at the 2019 IISS Shangri-La Dialogue:

"[I]t is well worth the U.S. forging a new understanding that will integrate China’s aspirations within the current system. … China will expect a say in this process, because it sees the present rules as having been created in the past without its participation. This is an entirely reasonable expectation…. The world…has to adjust to a larger role for China."

U.S. hegemony in maritime East Asia had provided the United States near absolute regional security. Nonetheless, acknowledgement of bipolarity does not require the United States to cede East Asia to Chinese hegemony — U.S.-China competition will persist. But it will reduce the risks of competition and constrain unchecked Chinese power and strategic ambitions.

The United States must continue to modernize its military capabilities and maintain extensive cooperation with its security partners, but the navy’s high-profile challenges to China’s maritime claims, including its frequent freedom of navigation operations, do not reassure U.S. security partners in East Asia, but they elicit Chinese belligerence that exacerbates U.S.-China tension.

The United States must maintain defense cooperation with Taiwan, but recent up-tempo U.S. Navy transits of the Taiwan Strait do not contribute to deterrence or to Taiwan’s security, but they elicit Chinese countermeasures that exacerbate cross-strait tension. U.S. charges of China’s ideological incompatibility with international cooperation and global norms are not only unpersuasive to other countries, but they also suggest U.S. unwillingness to acknowledge Chinese interests or a Chinese role in global affairs, encouraging greater Chinese challenges to American leadership.

The United States will continue to exercise global economic leadership, but it can no longer dominate the global trade order. And it is foolhardy to think that its can decouple economic relations with China – there is mutual trade and supply chain interdependence requiring cooperation. But the U.S. trade and technology war against China signals its intent to derail China’s economic growth and restore U.S. military and economic preeminence. U.S. adjustment requires negotiated agreements, as well as targeted independent U.S. strategic adjustments of the terms of trade to protect American interests against China’s state-managed economy and state-owned enterprises.

Cooperation despite competition

The U.S.-Soviet Cold War was an anomaly in diplomatic history. The norm through the millennia is that political dialogue, negotiation, and trade persist amid heightened great power competition. But in recent years the U.S.-China security competition has infused the entire agenda of U.S. policy making. The Trump administration’s “all-of-government” strategy is a major cause of this trend and it has been detrimental to a wide range of U.S. interests that require negotiation and cooperation.

The absence of U.S.-China cooperation on containing the spread of the coronavirus has contributed to the global pandemic and to great human, economic, and societal costs. But there are opportunities for cooperation. First, global health emergencies are not zero-sum developments. U.S. vilification of China’s role in the pandemic to mobilize a global anti-China coalition cannot alter the power transition nor contribute to containing the virus, but it undermines cooperation to minimize economic costs and death. And it is clear that both the United States and China failed to respond in a timely manner to warnings of an emerging pandemic and misled their people over the severity of the threat. Neither country can claim the moral high ground. Second, cooperation requires Chinese transparency to allow early scientific collaboration on containment and treatment. Third, the United States must reestablish its senior specialists’ dialogue with China to maximize collaboration and timely responses to potential crises. Fourth, the United States must abandon unilateralism and work with China to strengthen the World Health Organization’s global role in combatting global disease.

U.S. leaders must reengage China on counterterrorism cooperation. First, effective intelligence cooperation requires the support from the highest leadership. Second, as the United States withdraws its military forces from Afghanistan, U.S.-China cooperation on post-U.S. Afghan political stability does not exist, with implications for resurgent terrorist activities. Third, although the United States and China compete for strategic influence in the India Ocean, counterterrorism cooperation and promotion of political and economic stability in Pakistan are common interests. Fourth, the United States and China have multiple conflicts of interest in the Middle East, but neither has an interest in instability that fosters unchecked terrorist recruitment and violence. On the contrary, stable and developing Middle Eastern countries is a common interest and neither country should assess the other’s aid programs as detrimental to its security.

China and the United States share vital interests in constraining North Korean and Iranian nuclear capabilities. Nonetheless, in the absence of senior dialogue and functional cooperation, U.S.-China non-proliferation cooperation efforts have all but ceased. The Trump administration’s unilateralist approach toward North Korean and Iranian proliferation has failed. North Korea has consolidated its nuclear capabilities and it has sped up its testing of nuclear-capable missiles and the time Iran would need to produce a nuclear weapon has been cut shorter. U.S. security requires engagement with China in a substantive and high-level non-proliferation dialogue and cooperation.

The United States has an interest in stopping illegal trade in dangerous drugs. The Trump administration has focused on smuggling of fentanyl from China into the United States. Over a 12 month period in 2018-2019, nearly 35,000 Americans died from fentanyl overdose. Nonetheless, Chinese cooperation has been intermittent, at best. In the context of the U.S. trade war against China and U.S. ideological attacks on the Chinese Communist Party, Chinese leaders have little incentive to help the United States manage its domestic drug problem.

The United States and China have a common interest in managing global climate change. As the two largest global emitters of CO2 gasses, no global effort to manage climate change can succeed without U.S.-China cooperation. And both the United States and China have experienced the effects of climate change on their societies and economies. But with the Trump administration’s all-of government policy, there is no longer a bilateral dialogue on climate change. Management of global problems requires shared leadership, not a competitive effort to promote zero-sum gain.

Realizing U.S. interests requires robust embassy staffing. In the decades after normalization of relations in 1979, embassy staffing expanded as management of common interests required extensive and regular consultations and cooperation. But during the Trump administration embassy staffing has declined and embassy officials are increasingly idle, as the administration deems dialogue and cooperation as harmful to national security. This is a false and costly assessment.

The United States and China are destined to compete. But they are neither destined for war nor a cold war. Unlike U.S.-Soviet relations, the United States and China are not engaged in an ideological struggle in which each side believes that resistance to an insidious threat to its political system requires total diplomatic warfare. And, unlike the Soviet Union, rising China has not been a revolutionary state that has isolated itself from or sought to overturn the global economic order. Since the end of the Maoist era, all Chinese leaders have believed that China benefits from participation in and support for the U.S.-led post World War II economic order. China’s participation in the global trade order has contributed to its rise and to U.S.-China competition, but it also contributes to international stability and opportunities for cooperation.

China’s rise challenges U.S. interests, including its East Asian alliances, and American resistance challenges China’s interest in a revised regional order that offers China greater security. But the power transition does not preclude restrained competition nor engagement and cooperation. Unilateralism has never secured U.S. interests, and in the future unilateralism will be even less effective and more costly. Constrained competition and cooperation requires Chinese reciprocity. But U.S. unilateralism and cold war policies do not serve American interests. The United States and China will compete where they must, but there are opportunities to cooperate on common interests. This is the challenge of leadership in the United States and China.