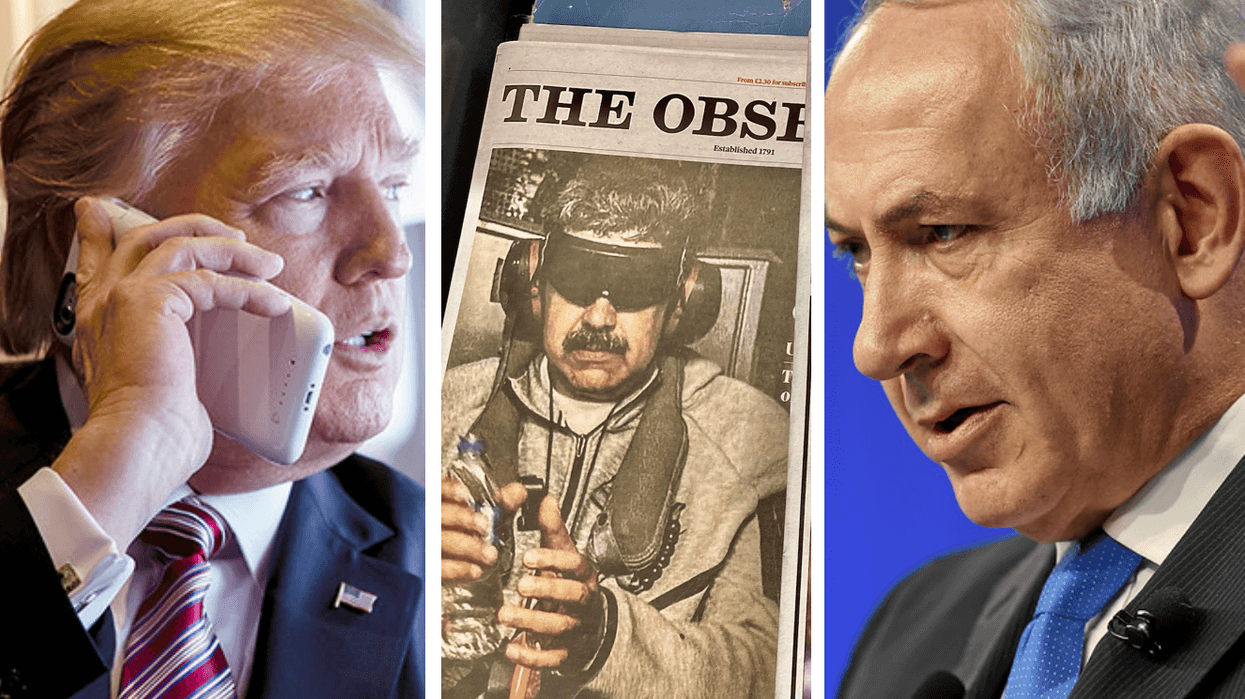

As President Donald Trump unveiled his long-awaited peace vision for the Middle East alongside Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in the White House’s East Room on January 28, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan’s response came very sharp and swift.

As one of two Arab countries that have diplomatic relations with Israel, Jordan did not send its Ambassador to attend the unveiling of the plan. The kingdom’s Foreign Minister, Ayman Safadi, issued a statement after the plan’s revelation reaffirming that the establishment of an independent Palestinian state on the border established on June 4, 1967, with East Jerusalem as its capital, is the only path toward comprehensive and lasting peace.

Awareness of the implications

Amman’s explicit position reflects the government’s awareness that it would be the first country to suffer the consequences of the so-called “deal of the century” should it be implemented. It emanates from Amman’s fear that the two-state solution could be jeopardized. If that happens — and Trump’s vision moves the conflict in that direction — Amman will find itself dealing with various threats, whether geographic, demographic, or security-related.

DuringTrump son-in-law and adviser Jared Kushner’s visit to Jordan last year, King Abdullah II said that any peace plan needs to be in accordance with the 2002 Arab Peace Initiative. However, this is not the case with the proposed plan.

What the vision offers, rather, are serious challenges to Jordan’s national interests over the long term. One of these obstacles relates to the kingdom’s historic role as the Custodian of the Islamic and Christian holy sites in Jerusalem. This role is so important to the Hashemites as they are direct descendants of Prophet Muhammad. It can also be seen as a source of the monarchy’s legitimacy as ruler of Jordan.

Yet while Trump said that Israel would “work closely” with King Abdullah II “to ensure that the status quo of the Temple Mount is preserved and strong measures are taken to ensure that all Muslims who wish to visit peacefully and pray at the Al-Aqsa Mosque will be able to do so,” his vision lacks a clear identification of Jordan’s Custodian role. The fact that the peace plan stresses that Jerusalem should remain Israel’s “undivided city” suggests that Amman would eventually find itself working with Tel Aviv on maintaining the sites, which will then be under Israel’s sovereignty. This weakens the kingdom’s historic role.

Jordan also has valid concerns about the Palestinian refugee crisis. Trump’s plan gives Israel the green light to proceed with annexing West Bank settlements and the Jordan Valley. With over two million registered Palestinian refugees in the country, such an annexation raises the possibility of a significant influx of Palestinians seeking asylum in the kingdom. Additionally, annexing the Jordan Valley would complicate the geographical connection between Jordan and Palestine, impact the kingdom’s economy, and present a potential threat to Amman’s national security.

Unstable economy

The plan’s unveiling comes at a time when the kingdom has been suffering increasing economic straits over the last few years. One of these obstacles relates to the high rates of joblessness, which includes 40 percent youth unemployment.

Another challenge is poverty. In November, a survey found that 64 percent of Jordanians think that poverty is the most important factor that would lead to domestic violence and that children and women are the most to be vulnerable to domestic violence. The public debt would also be another economic strait that Amman faces. In December, Jordan’s finance minister, Mohammad Al Ississ blamed regional factors on the spike in public debt that shot up by almost a third in a decade to 30.1 billion dinars ($42.4 billion) in 2019, equivalent to 97 percent of GDP.

Although there are other challenges too, such as the budget deficit and corruption, these issues are long-existing in Jordan. However, they have worsened lately due to several factors, including the influx of more refugees from war zones and the decline of foreign aid.

For instance, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) decided in 2011 to extend $5 billion in financial aid to development schemes in Jordan over five years, with each state contributing $1.25 billion. However, the package was not renewed after its expiration. Amman has also been, reportedly, frustrated that billions of dollars in Saudi investments have been delayed since a joint fund was enacted in 2017. Jordan’s refusal to send forces to Yemen to fight the Houthis and its dealing with the Gulf crisis displeased the Saudis and therefore, contributed to this delay.

Although Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Kuwait pledged an aid package of $2.5 billion to the kingdom after the widespread protests that led to the resignation of prime minister Hani Al Mulki in 2018 not much has been delivered until now.

Today, Jordan relies on the U.S. economic and military aid, which amounts to more than $1 billion annually. There is also a reliance on European aid, particularly Germany’s, which is the second-largest bilateral donor to the kingdom, providing more than half a billion euros of annual support.

Potentially, there may be hopes on that Qatar’s Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani’s upcoming visit to Jordan on February 23 — which will be his first visit to the kingdom since March 2014 — would result in providing Jordan with some aid, but that remains to be seen.

Balancing the relations with both Ramallah and Washington

Jordanians have loudly rejected Trump’s plan as several protests against it erupted since it was released. The Jordanian tribes, who are considered one of the state’s pillars, are also never going to accept the vision as they have their own concerns too, such as becoming a minority in their own country due to more Palestinians migrating to the kingdom.

It’s also possible the annexations envisioned in Trump’s plan would lead Jordanians to increasingly demand the cancelation of the 1994 Israeli-Jordanian peace treaty, known as “Wadi Araba,” and the Jordan-Israel gas deal that was struck in 2016. That is because on top of the fact that these agreements were never popular amongst the citizens, they will see the move as an attempt to settle the conflict on the kingdom’s expense.

Yet despite the fact that last year, the kingdom has reclaimed border lands that Israel was allowed access to under the peace accord — Baqura and Al Ghamr — the government knows that canceling the peace treaty would have a significant political cost.

Moreover, the gap between Jordan and Israel has been clearly growing over the last couple of years. Last month, King Abdullah II said in an interview that Jordan’s relationship with Israel “has been on pause for the past two years.” This came a few months after he said in November that his country’s relations with Tel Aviv were at an all-time low.

Meanwhile, Amman is dealing with these challenges on its own. Jordan appears to be aware that the Arab League’s rejection of Trump’s plan is on shaky ground because the actions and approaches of some of member countries contradict their public vote.

It is apparent that the Trump administration has put a long-standing U.S. ally in a difficult position. Clearly, it did not take into consideration the peace plan’s impact on Jordan, let alone the fact that it never revealed the plan to Amman, thereby abandoning the kingdom’s significant role in the peace process.

Indeed, Jordan would want to avoid a direct clash with Washington for various reasons, most importantly because of Amman’s reliance on the U.S. economic and military aid. Thus, it will have to deal with the challenge of balancing its relations with the Palestinian leadership against its ties with the White House, while not abandoning its firm position. What remains to be seen is whether the kingdom will be able to create such a balance and remain steadfast amid any pressures.