In the past half century during which I have reported on Middle Eastern politics, society, and development — now de-development in a half dozen states — never have I witnessed the breadth and wanton savagery of the armed conflicts that plague our region today. There is no single cause. Many local, regional, and international factors drive conflicts across the Middle East, with traditional geo-strategic and ideological forces now joined by environmental and economic collapse in some haplessly mismanaged lands.

Yet hovering above all the territorial conflicts, state and non-state warring armies, and aggressive ideologies that waft across our region as regularly as the annual early spring warm desert winds is one force that underpins them all: The Ghost of Napoleon Bonaparte, whose invasion of Egypt in 1798 initiated over two centuries of continuing foreign military interference across the entire Arab region.

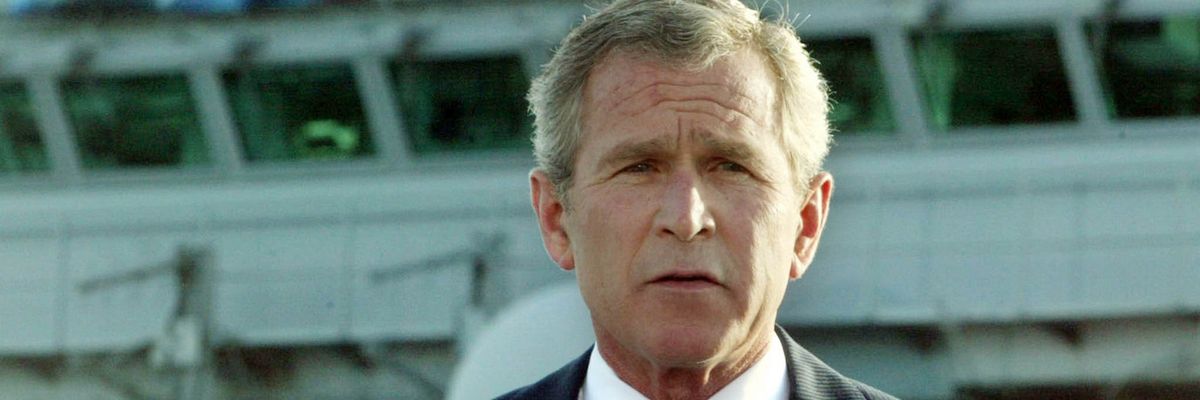

For the past two centuries and, particularly the last three decades, direct foreign military intervention in the affairs of ostensibly sovereign and independent states has been perhaps the most consistent and destructive common denominator that shapes our region’s worsening condition. Direct warfare by foreign powers almost always paves the way for decades, if not centuries, of continuing instability—whether in the cases of Napoleon in 1798, the Soviet Union and the United States in Afghanistan in the decades after 1979, the U.S. in Iraq in 2003, or Russia, Iran, and seemingly half the world in Syria since 2015.

Direct foreign military attacks or other “security” activities inside Middle East lands inevitably create traumatic local power imbalances that portend chronic local ideological conflicts, and spark resentments and resistance to the foreign invader or to the invader’s local ruling ally. Foreign invaders also create local authority vacuums that open the door for other states to intervene (see Iraq, Syria, and Libya), and also create the ideal spawning ground for radical, militant, resistance, or terrorist movements of all stripes. Israel repeatedly encountered this instinctive local resistance to its predatory militarism in Lebanon and Gaza, as did the U.S. and the Soviet Union in Afghanistan, and the U.S. and its allies in Iraq.

Almost nothing good emerges from direct foreign militarism in the Middle East, and even when the fighting stops surreptitious foreign support to local warring parties also perpetuates tensions and clashes, which only spur economic waste, corruption, collapse, and widespread poverty and suffering among the citizenry.

It is clear now that foreign militarism plays a destructive and sustained role in the two biggest problems that now tear apart much of the Arab region (and also touch on non-Arab Mideast states like Iran, Turkey and Israel). The first is mass pauperization that now sees over two-thirds of all Arab citizens living in poverty or vulnerability, in states that have reached or approach bankruptcy and allow citizens no meaningful political rights. This will get much worse because all prevailing economic trends that could counter it are flat or negative (trade, tourism, direct investment, remittances, job creation).

The second problematic big regional trend—very much states’ reactions to their citizens’ helpless pauperization—is the growing militarization and securitization of governance. This is evident in bloated military and security budgets that are controlled by a handful of unelected, unaccountable leaders, and expanded use of anti-terrorism laws since September 2011 to deter or imprison domestic political foes, or prevent any independent political expression by the public (see Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain). Foreign militarism since the 1940s has inevitably promoted local military rule within Arab states. The incompetence, autocracy, and corruption of Arab military rulers since the 1970s have driven economies into the ground, and sparked the nonstop street uprisings we witness today across the region.

The centuries of cumulative interventions by foreign powers inside Arab states reached a new peak in the past eight years in Syria, where dozens of foreign and regional actors that joined the fray inside the country charted new ground in the historical legacy that had mostly seen big power, usually Western and colonial, interventions in the region’s affairs.

Of course Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, Persian, and other imperial dominance in the region across time all played a role in defining the Middle East as a frontline battlefield in the recurring waves of global imperial dominance and cultural influence. Starting in the 19th Century, however, as imperial powers started to come to terms with their imminent historical demise, the British and the French mostly wrote the book on the ugly heritage of battling for strategic supremacy in our region. The 20th Century saw foreign powers fight at will in the Middle East, and also provide indirect political and “security” support to their favorite local partners, allies, surrogates, and stooges, who kept fighting it out inside Arab countries that proved to be only nominally sovereign and independent states.

The civil war in Syria that started in 2011 was the logical outcome of this legacy. It mirrors other states where authority and legitimacy collapsed in the eyes of their own people, and the sovereign control of their lands and resources succumbed to the many foreign actors that came in to save the dying beast or bite off pieces of its carcass. Syria offers one of the most important examples of this, given the wide variety of warring parties that joined its several overlapping local, regional, and global wars.

The fighters in Syria included dozens of Arab states and non-state armed groups, local militias and tribal forces, regional non-Arab powers like Iran, Turkey, Israel, and Hezbollah and their clients, wannabe regional powers like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, leading global powers like the U.S. and Russia, second-tier powers like the U.K. and France, and a few smaller countries around the world that joined directly or provided mercenaries mostly to win credits with bigger Arab or foreign powers.

The eight-year war in Syria is at once a consequence and a high-water mark of sustained foreign military interventions in the Arab region, and a harbinger of how such foreign and local militarism will operate there for years to come. We can already see in Libya, Lebanon, Yemen, Somalia, Iraq and scattered other corners of our troubled region several noteworthy legacies of today’s foreign militarism in Syria and its antecedents since Napoleon.

Regional and foreign powers’ rolling interventions in Syria have redefined how such powers engage across the region, where two opposing loose alliances, loosely allied with Saudi Arabia or Iran, now face off—each comprises Arab states, regional Arab and non-Arab powers, global powers, and local non-state actors. The sheer number and variety of foreign forces that directly or indirectly fought in Syria portend badly for fragile states whose illusory sovereignty can collapse at any moment in the face of dozens of armed actors that pounce like wolves circling a dazed gazelle. The “international community” that actively joined and fueled the fighting also responded weakly to the alleged and real war crimes on both sides This suggests that the “international community” is something of a fiction, but also that, whatever it represents, it can live with the Middle East’s continuing authoritarian, lawlessness, and violent political systems — as long as the violence, refugees, terrorists, and turmoil remain in the Middle East.

Indeed, global and regional powers actively engage in cross-border militarism and neo-colonialism that we can see in several arenas: Washington’s support for Israeli settlements expansion and annexations of occupied Arab lands, and its lingering presence in Syria and Iraq; Russian and American support for Turkish incursions into northern Syria; Saudi Arabian and Emirati moves to control parts of the south of Yemen for their own strategic aims; British and American direct involvement in the war on Yemen; and, French, Emirati, Russian, and Egyptian support for the rebel forces of Khalifa Haftar in Libya, to mention only the most obvious.

These are only the most current but ongoing consequences of over two centuries of non-stop foreign military and political interference that our region has experienced, with devastating long-term impacts. Internal and regional wars, in a climate of very high Arab military spending, continue to propel countries back into dilapidated or vulnerable conditions every few decades. The Arab examples of this only increase, including Lebanon, Palestine, Libya, Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, and Jordan. Non-Arab Iran, Turkey, and Israel face their own challenges, as they simultaneously suffer the damages of external militarism and also engage in it themselves around the region.

It is time for all foreign and regional powers to start learning the hard lessons of these historical trends and instead seek non-violent diplomatic solutions to challenges they now mostly address with their guns blazing. A regional population of half a billion poor and powerless people held in check by hundreds of billions of dollars of military spending linked to foreign troops who enter our countries at will is probably a far greater real threat to their wellbeing than anything they can imagine today.