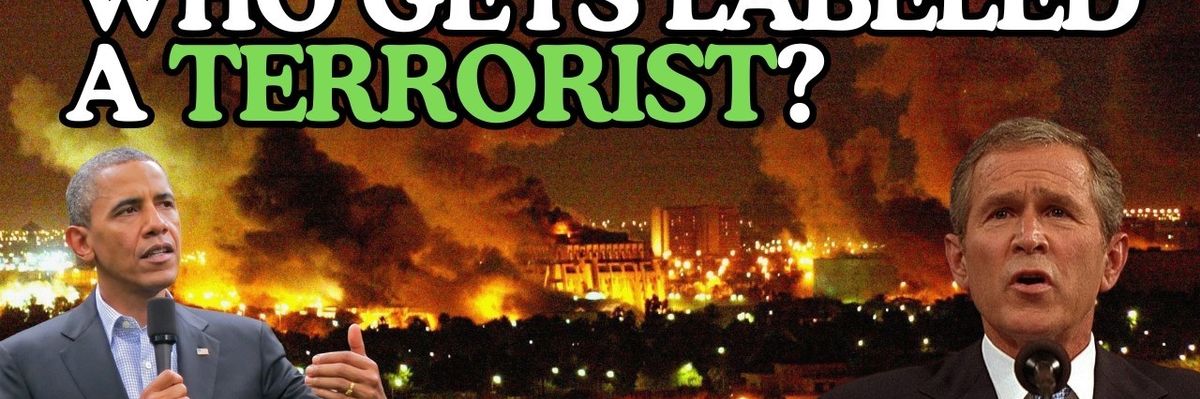

What is terrorism? And who decides who is a terrorist and who isn’t? This vague, politically malleable concept has become the justification for a global American war against terrorism that spans 78 countries — more than a third of all nations. At home, it's handed local police departments $34 billion to buy military equipment, turning terrorism into a catch-all excuse for militarizing American communities.

In this episode of Always at War, we talk with national security law expert Elizabeth Beavers to unpack how terrorism designations work as political tools rather than security measures — keeping Nelson Mandela out of America until 2008, shutting down the biggest Muslim charity in the country, and now threatening Gaza protesters with prosecution.

We trace how terrorism laws originated in anti-Palestinian activism and evolved into a legal framework so broad that it criminalizes giving "expert advice" to designated groups. Through examples like the Holy Land Foundation — whose leaders went to prison for charity work the government admitted reached legitimate recipients — we show how these laws are designed not to stop violence, but to suppress political dissent and enforce American geopolitical interests.

The episode reveals how America’s Global War on Terror did little to eliminate “terrorism” – a potentially impossible goal – but to create an endless justification for global American dominance.

By declaring war on a concept rather than specific enemies, we've built a system where peace becomes impossible and every corner of the globe becomes a potential battlefield — all while the vague definition of "terrorism" expands to include anyone who challenges American interests.

Please check out the latest episode:

- How a post-9/11 law could enable a crackdown on speech ›

- 9/11 militarized law enforcement and made every American a suspect ›