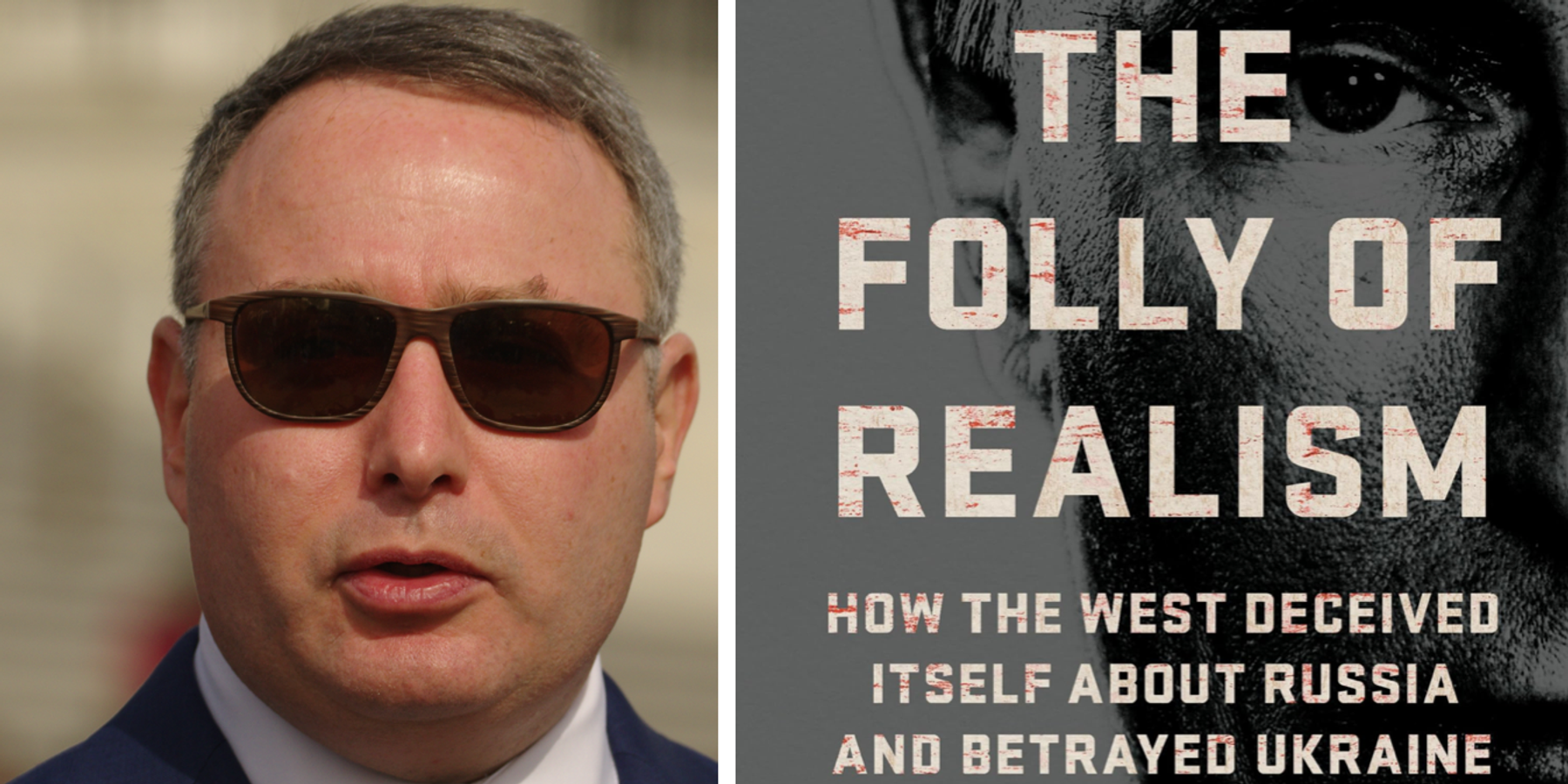

Alexander Vindman’s recent book, “The Folly of Realism,” throws down the gauntlet, as the name suggests, at the “realists” he thinks were responsible for failing to deter Russia and seize opportunities for defense cooperation with Ukraine.

According to Vindman, the former National Security Council official who testified against President Trump during his impeachment trial in 2019, this “realist” behavior incentivized Moscow’s continued imperialist predations, culminating in the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Vindman’s proposed antidote to what he considers the lapses of the past three decades is Benjamin Tallis’ framework of "neo-idealism," a lightly repackaged menagerie of post-Cold War transatlanticism’s greatest hits that is bizarrely presented as a novel outlook on the international system.

Fully squaring all the historical misjudgments presented in these 240 pages demands an exegesis of at least as many pages, and not just because there are so many — though one certainly doesn’t find themselves pressed for material — but because Vindman’s central arguments flow from larger, decades-long narratives about Russia and post-Cold War U.S. policy that simply do not stand up to scrutiny.

Nuclear policy emerges as one of the main causal drivers of Vindman’s story. No one can quarrel with the proposition that successive administrations took seriously the cause of nonproliferation in the post-Soviet sphere — they had every reason to — and that nuclear concerns shaped U.S. engagement with the Russian Federation to a significant even if not decisive degree.

But to suggest, as Vindman does, that the thrust of early U.S./NATO policy toward Russia boils down to nuclear concerns is to lapse into a narrowly tendentious reading of events that history doesn’t lend itself to.

Vindman, who interviewed the officials involved in negotiating the 1994 Budapest Memorandum from the U.S. side, was careful not to retread the solecisms so heartily indulged by many of his allies and fellow travelers. He concedes, and not insignificantly so considering how deeply this narrative has entrenched itself in recent years, that the signed memorandum did not contain U.S. security guarantees to Ukraine in exchange for relinquishing its supposed nuclear arsenal.

“There's no question in my memory and in my mind that the Ukrainians understood completely the difference between security assurances and Article 5 security guarantees. And they understood they were getting security assurances,” Vindman quoted Nicholas Burns, Senior Director for Russia, Ukraine, and Eurasia Affairs at the National Security Council, as saying.

These assurances, as I explained with my colleague Zach Paikin, did not commit the U.S. to undertake any specific commitments beyond what it agreed to in previous treaties. Indeed, it’s precisely because the memorandum was not legally binding and contained no concrete defense commitments that it did not have to be ratified by the Senate, as all treaties must be.

But this whole “denuclearization” business calls for a greater degree of technical scrutiny than Vindman affords it. Three of the 15 states that emerged from the Soviet collapse — Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Belarus — did not in fact “inherit” thousands of nuclear weapons. These were Soviet nuclear weapons, stationed across the Soviet Union but controlled from Moscow. After the Soviet collapse, these became Soviet nuclear weapons left over on the territories of former Soviet soviet states.

It was never established that Ukraine exercised legal, political, or operational control over these weapons, nor that the nascent Ukrainian state disposed of the considerable resources required to maintain them. Ukraine did not, in this sense, possess a nuclear inheritance that could be bartered away for Western security guarantees or anything else.

What we have before us, then, is not a geostrategic question but a largely operational challenge of removing these weapons, to which Ukraine had no recognized claim, from Ukrainian territory in an orderly way. This rather unremarkable process, though unquestionably a major part of the story of 1990s U.S.-Russia relations, is lent a degree of long-term political significance by Vindman that it simply doesn’t deserve.

So, what, then, is the larger picture and how does it fit into Vindman’s argument that the West’s woes stem from a decades-long policy of, if not appeasing, then at least turning a blind eye to “Russian ambition and exceptionalism?”

One cannot help but escape the sense that Vindman’s story suffers from the plight of Alexander the Great, who wept that he had only one world to conquer. His analysis is strongly tinted by the endless, yet strategically vacuous, expressions of goodwill, optimism about Russia’s Western path, and other such millenarian effusions that characterized U.S.-Russia relations up to the mid-2000’s.

But in the most important ways, U.S. policy has been guided all along by something quite similar to Vindman’s neo-idealism. The Soviet collapse gave Western leaders a generational opportunity to go about the difficult but necessary task of building a new security architecture that includes mechanisms not just to deter Russia, but also to engage it in ways that do not lead to security spirals in Eastern Europe. U.S. policymakers, less driven by balance of power concerns than they were enchanted by the seductive vision of a Europe “whole and free,” brushed aside the concerns of George Kennan, Robert McNamara, and a great many others to greenlight the limitless expansion of NATO, an alliance explicitly arrayed against the Russian Federation’s Soviet predecessor.

It seems to be a source of consternation for Vindman that Ukraine was not invited into NATO in those early days. Vindman’s implication that Ukraine was thus abandoned to Russia’s sphere of influence incorrectly frames the problem at hand. Washington’s fervid devotion to NATO’s “open door” membership policy and dogged refusal to countenance any framework for delimiting NATO’s boundaries shows that the lack of progress in this area was purely tactical in nature and certainly not grounded in systemic realist thinking.

There is also the peccadillo of democratic values, defense of which is supposed to be NATO’s entire raison d’être. In point of fact, polling shows most Ukrainians had no desire to join the alliance until as late as the mid 2010s, when it became impossible due to outstanding territorial conflicts with Russia.

Vindman’s indictment of what he wants the reader to believe passes for “realism” — more on that shortly — hinges on viewing Russia as an innate aggrandizer emboldened by the failure of successive U.S. administrations to deter it.

It all falls apart upon the most basic attempt at a more sophisticated structural analysis — one which would find that Russia’s behavior is consistent not with a grand strategy of conquest for its own sake but with what most realists would identify as balancing behavior in response to the eastward expansion of Western military and security institutions into the post-Soviet sphere, and Russian actions intended to preemptively deny such expansion.

Trudging through this book, with its unique blend of endless encyclopedic tedium heaped on top of the analytical equivalent of a children's pop-up story, can be best likened to navigating a swamp that’s shallow yet impossibly vast. But this rather unpleasant journey at least gives the reader ample time to meditate on the book’s central conceit.

Vindman unfortunately displays a woefully inadequate grasp of that which he tries to impugn: at no point does he demonstrate anything more than a cursory understanding of realist approaches to the issues he tries to elucidate.

One is left grasping in vain for any evidence that Vindman can pass the simple theoretical Turing Test of explaining any school of realism — let alone to distinguish between them — to the satisfaction of a realist. But Vindman’s underlying thrust is not to meaningfully engage with realist arguments on Ukraine’s post-Soviet transition, 1990’s U.S.-Russia relations, or nuclear proliferation in the former Soviet sphere.

Instead he wants to launder what has largely been an idealist, atlanticist handling of these issues since 1991 by pinning the neoconservatives’ manifold sins and lapses on a haphazard cluster of ideas and approaches clumsily christened by him as “realism.” There was no realism in the strategically shortsighted decision — condemned by many realists at the time — to enable successive waves of NATO expansion and encourage, against genuine U.S. and European security interests, the integration of post-Soviet states into the West’s collective defense umbrella.

The well-established idealist framing of American engagement with competitors as a manichean confrontation between democracy and autocracy is anathema to realism and, indeed, to a healthy understanding of U.S. national security priorities.

But it is true that actual realist ideas are rapidly making their way back into the foreign policy discourse after decades in the wilderness. As is always the case after an exiled intellectual movement rediscovers the levers of power, there will and should be a vigorous debate on what form these ideas will take when filtered through the vicissitudes of American politics and applied to the pressing challenges of our time, including the Russia-Ukraine war and the broader task of building a sustainable architecture of European security.

And whatever missteps are made along the way pale in comparison to a disastrous status quo that can be described by many names. Realism, it is not.