For successive U.S. administrations, the big region below the American southern U.S. border was considered a bit of a backwater.

Sure, there were a few internal conflicts left outstanding, a couple of old-school leftist insurgencies still in operation, and the perpetual problem of drug trafficking. But after the Soviet Union collapsed, Latin America was never thought of as an epicenter of great power competition. The United States, frankly, didn’t have to worry about a geopolitical contender nosing into its own neighborhood.

The Trump administration, however, isn’t like any other administration before it. Trump campaigned on stopping narcotics from entering the U.S., defanging the drug cartels that have proven to be almost as powerful as the Mexican state, and dealing with irregular migration. So Latin America is now a center of gravity for U.S. foreign policy. Secretary of State Marco Rubio chose the region for his first trip as America’s top diplomat.

As we speak, the USS Gravely, a guided-missile destroyer, is steaming toward the Gulf of Mexico on a mission that Gen. Gregory Guillot, the commander of U.S. Northern Command, says is intended to protect the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the U.S.

If the Trump administration’s first eight weeks tell us anything, it’s that the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, which carved out the Western Hemisphere as Washington’s exclusive sphere of influence, is again at the forefront. Whether it’s threatening unilateral U.S. military action against the Sinaloa and New Jalisco Generation Cartels in Mexico, yelling about taking back the Panama Canal, or leveraging tariffs to coerce smaller states to cater to his policy priorities, Trump is treating the entire area as his own personal piñata.

To be fair, Washington has won some short-term wins. Either out of deference to a superpower or because they don’t have other alternatives in the short-term, the region’s governments have largely acceded to Trump’s wishes. Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum, for instance, has been far more aggressive against the cartels than her predecessor and mentor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) ever was during his six-year presidency. Law enforcement operations, often conducted by the Mexican military, have resulted in a steep increase in arrests, the seizure of 7 tons of narcotics and the dismantling of more than 100 fentanyl labs over a 10-day period.

Trump’s erratic tariff threats, like slapping a 25% tax on Mexican goods destined for the U.S. market, compelled the Mexican government to deploy an additional 10,000 troops to the U.S.-Mexico border for counter-narcotics operations (although how successful this operation will be in the long-run is up for debate). And while the evidence is circumstantial, it’s likely Mexico’s decision to hand over 29 of the country’s senior cartel leaders to the U.S. Justice Department had something to do with the tariff cudgel Trump is so fond of yielding.

There is movement further south as well. Despite Panamanian President José Raúl Mulino’s vocal declarations that the Panama Canal will forever remain under Panama’s control, his government has nevertheless tried to mollify the Trump administration by cooperating with Washington’s deportation schemes, getting out of China’s Belt and Road Initiative earlier than anticipated, and announcing an audit of a Hong Kong-based company that owns two ports on either end of the strategic waterway.

Those ports will soon be in the hands of BlackRock, a development China is none too happy about.

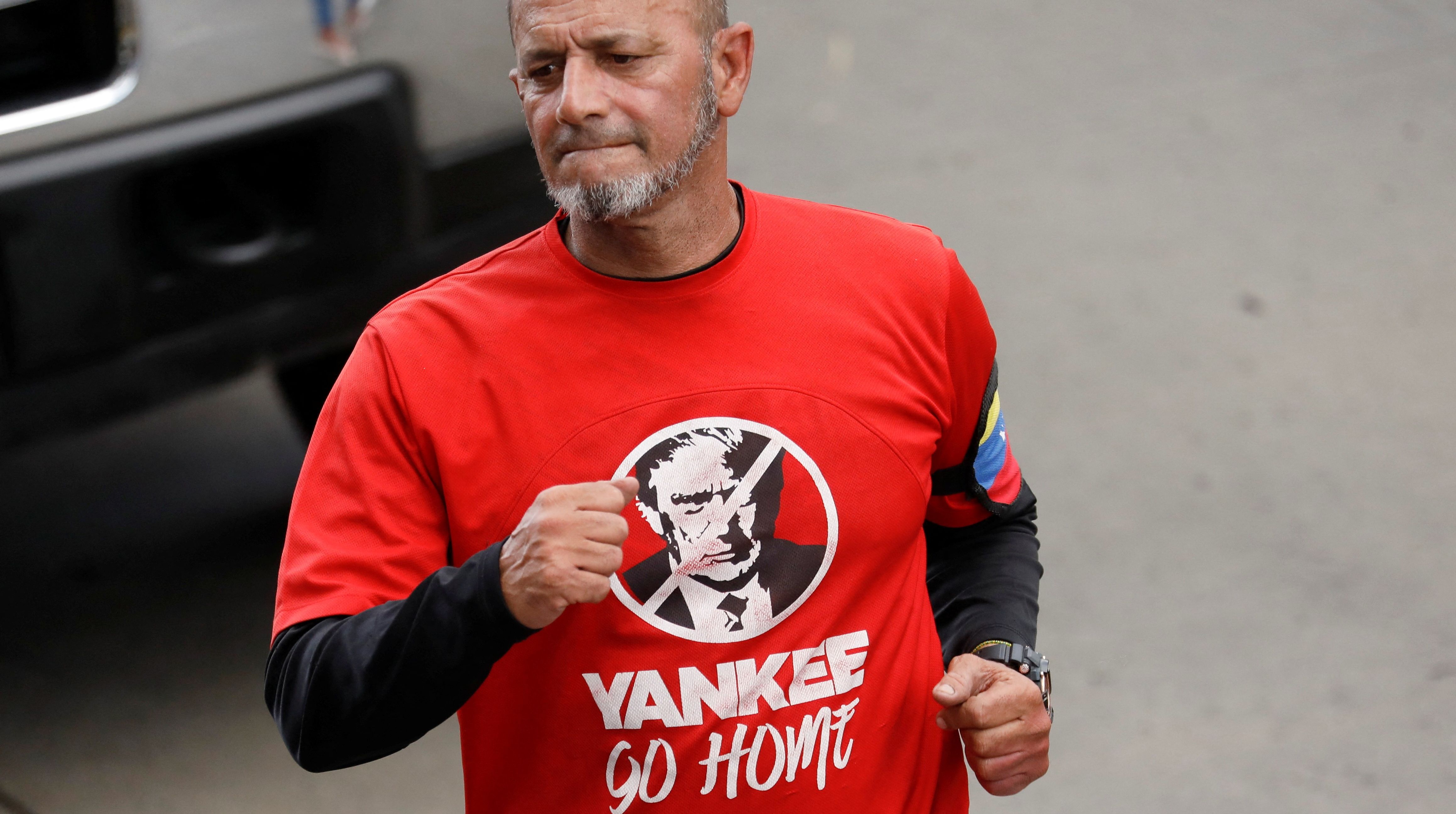

The heavy-handed U.S. approach is also working to an extent with some of Washington’s few adversaries. Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro, the same man Trump tried to dethrone during his first term by recognizing his main competitor, Juan Guaidó, as Venezuela’s rightful president and instituting a maximum pressure sanctions policy on the Venezuelan economy, is now exploring whether a detente with Trump’s second administration is possible. Despite labeling Maduro’s regime an enemy of the state and alleging that it cooperates with Venezuelan gang Tren de Aragua to destabilize the U.S, Maduro agreed last week to resume accepting flights of Venezuelans who were deported from the U.S., likely in an attempt to ensure Chevron can continue to operate in Venezuela.

The record at this early stage is clear: Trump can legitimately claim that his tactics have produced results.

U.S. policymakers, however, would be wrong to assume that these tactics will work over the long-term or don’t have costs attached to them. Today, Latin American countries might be wary of confronting the U.S. But that wariness is unlikely to last if the Trump administration continues to throw around the stick at the exclusion of the carrot. Even small states have pride, dignity and an aversion to getting mercilessly kicked in the teeth at every opportunity. Look no further than Iran and North Korea, two relatively weak states that continue to thumb their nose at Washington’s demands notwithstanding the economic vise the U.S. has put them in.

Colombia, Peru, Mexico and Panama aren’t Iran and North Korea, of course. Outside of tariffs, it’s hard to envision that even Trump would go so far as to lock these countries out of the U.S. financial system, station warships off their coasts without their consent or shut down their respective embassies on U.S. soil. Yet Trump doesn’t have to do any of this to cause resistance and antagonism in these countries. The U.S. already has a bad reputation throughout Latin America thanks to its Cold War-era history of interventions, coup plotting and support for right-wing authoritarian regimes, particularly in Central America, which were more adept at killing civilians than servicing the basic needs of their populations.

Even more significant, Latin America has other options. In the past, these states couldn’t do much of anything to register their disapproval to U.S. actions. Most of them relied on the U.S. market and didn’t want to jeopardize the hand that fed them. Others relied on U.S. aid to ensure their militaries were still functioning. Outside of Cuba, Venezuela and Nicaragua, the region was America’s domain, a place where it could afford to be dismissive precisely because near-peer competitors didn’t have the capability or intent to challenge U.S. power.

But this is no longer the case. China isn’t about to displace the U.S. in Latin America but it’s by far a more palpable alternative for the region’s states today than it was at the turn of the century, when the Chinese economy was still scraping the bottom of the barrel. The statistics bear this out; between 2002 and 2022, trade between Beijing and Latin America increased from around $18 billion to over $450 billion. China provides investment and capital for major infrastructure projects in the region, from mines in Peru and ports in Ecuador to rails in Mexico and flashy soccer stadiums in El Salvador.

The Chinese aren’t doing all of this out of the goodness of their hearts—they’re doing it to undermine U.S. power in its own neighborhood.

The U.S. would be wise not to overreact. But it shouldn’t be making China’s work easier either. There’s a substantial risk that the Trump administration’s policy could be counterproductive. Hopefully Trump will recognize this sooner rather than later.

- Pushing the Global South into China's embrace ›

- With Rubio, Waltz, a harder line on Latin America looms ›

- Forecast in the Americas: Uncertainty with a chance of Trump | Responsible Statecraft ›

- US troops headed to Panama | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Bukele's dirty secret: He made deals with the worst gangs | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Former Air Force commando takes top LatAm job at NSC | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Latin America's hidden role in shaping US foreign policy | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Bolsonaro's son: I convinced Trump to slap tariffs on Brazil | Responsible Statecraft ›

- US non-profits 'in the tank' for Exxon, Chevron over Venezuela oil | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Is a new war on terror kicking off in the Caribbean? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Why Ecuador went straight to China for relief | Responsible Statecraft ›

- How US incompetence empowers China in Latin America | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Paradoxically, 'Donroe Doctrine' could risk US interests | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Trump's sphere of influence gmbit is sloppy, self-sabotage | Responsible Statecraft ›