This past Wednesday, Russian President Vladimir Putin sat down for an interview in which he yet again made clear that, despite the insistence of pro-diplomacy voices in the West, he was not ready to negotiate an end to the Ukraine war, because Kyiv’s uncertain battlefield prospects meant Russia could secure further advances by continuing the war.

“It would be ridiculous for us to start negotiating with Ukraine just because it’s running out of ammunition,” Putin told interviewer Dmitry Kiselyov, according to one particularly viral and widely cited tweet by Wall Street Journal chief foreign affairs correspondent Yaroslav Trofimov.

Except that’s not what Putin said. In fact, by reading the full text and seeing the quote in context instead of as a selectively edited soundbite, it’s clear he was putting out the exact opposite message:

"For us to hold negotiations now just because they are running out of ammunition would be ridiculous. Nevertheless, we are open to a serious discussion, and we are eager to resolve all conflicts, especially this one, by peaceful means."

What is true is that Putin once more restated the more stringent conditions for peace talks he adopted last year, namely that Moscow will not give up the four regions it officially annexed in September 2022 and that, given the state of the battlefield, Ukraine will have to accept the loss of this territory.

“Are we ready to negotiate? We sure are,” he said. “But we are definitely not ready for talks that are based on some kind of ‘wishful thinking’ which comes after the use of psychotropic drugs, but we are ready for talks based on the realities that have developed, as they say in such cases, on the ground.”

This didn’t stop the truncated version of the first quote from being spread far and wide on social media and being held up, often by reporters at top newspapers like Trofimov and other authoritative voices, as definitive proof that negotiations to end the war were impossible and that prolonged war is the only option.

“Republican leadership of the House cutting off military supplies to Ukraine has made Putin drop his pretense about desiring peace talks. He wants it all,” was Trofimov’s summary of the interview.

“Putin indicated he won't discuss surrendering territory annexed from Ukraine and appeared confident Russia’s army could advance further,” the Financial Times Moscow bureau chief Max Seddon reported, before offering the clipped quote as evidence.

“Russia spreads rumors about negotiations. Uncritical people write naive articles. US cuts off aid to Ukraine. Putin says — thanks, with your help I'll win the war [and] destroy Ukraine,” wrote historian Timothy Snyder, citing Trofminov’s summary.

“War criminal Putin doesn't want to negotiate, only to rape, murder & pilage innocent Ukrainians,” tweeted Belgian MEP Guy Verhofstadt. “The only way this war ends is if we step up and give Ukrainians what they ask for. Those in the West calling for negotiations serve this monster.”

Rep. Don Beyer (D-Va.) used it to claim the GOP’s hold-up of military aid was “fueling Putin’s aggression and the Russian war effort.” Identical arguments — that the truncated quote showed Putin’s talk of negotiations was a smokescreen, and that the only way to get to a peaceful end to the war is to double down on a military solution — were, and still are today, being spread by a wide variety of prominent, influential and often hawkish voices, largely piggybacking off Trofimov and Seddon’s misrepresentation of the remarks.

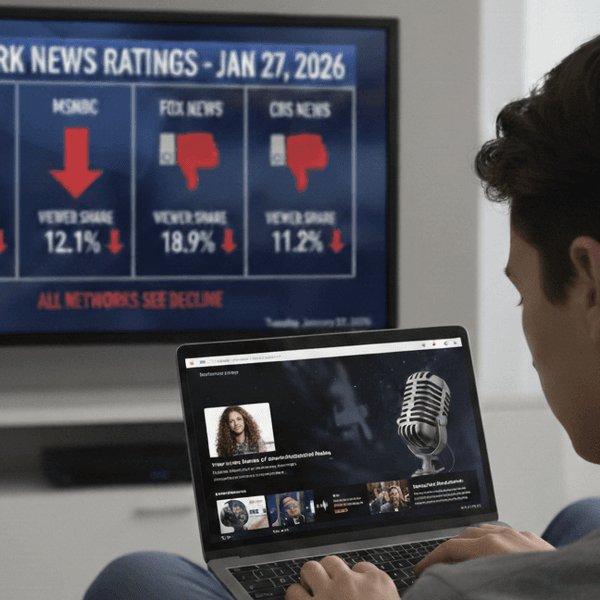

It’s not been much better outside of social media. Putin’s comments about negotiations were left entirely out of Western media reports on his interview at Reuters, the Associated Press, PBS and Voice of America. Only CNBC included the comments with the full quote; CNN also reported that “Putin said Russia would be willing to negotiate,” though citing only his remark about “realities on the ground.”

Others double down on using the shortened quote for a misleading framing, such as this Washington Examiner headline, or this Telegraph report. The latter went beyond merely the headline and opened by telling readers that Putin “has ruled out opening peace talks with Ukraine,” before putting together a composite quote from the interview that deliberately skipped over his remark that Moscow was open to talks and eager to resolve the conflicts diplomatically.

Why is this important? Hawks would charge that simply daring to correct the record here is a sign of suspicious pro-Putin sympathies. But willingness to negotiate has nothing to do with moral virtue: the violently repressive Saudi government, which recently went on an execution spree, also eventually negotiated an end to its horrific war on Yemen despite the horror it had unleashed on the country.

More recently, Hamas has shown a willingness to negotiate throughout the Israeli assault on Gaza, talks that bore fruit back in November with a ceasefire and hostage swap, none of which absolves it for the atrocities of October 7 or renders its members model citizens.

Just as in those cases, one does not need to trust in Putin here, an authoritarian and practiced politician, to proceed with talks. Peace negotiations are, by their very nature, carried out between parties without ample reserves of faith in and goodwill towards each other, and part of any talks involves devising a mechanism with acceptable security guarantees for each party that removes the need to rely on mere trust. The surest way to verify if someone is serious about such negotiations is to actually try them.

The fact that Putin insists he’s open to negotiations, albeit with major territorial concessions from the Ukrainian side, should be encouraging news for anyone who genuinely cares about Ukraine. The RAND Institute argued in January last year that the economic and social damage caused by a longer war outweighed the possible benefits of military reconquest of lost territory. Indeed, the effects of prolonging the war in search of a morally satisfying military victory have been devastating for the country: tens of thousands killed and wounded, widespread destruction of infrastructure, a demographic crisis, and massive debt that will leave the country vulnerable to rapacious creditors. Many thousands of Ukrainians are desperately dodging conscription to avoid dying in the war, with a plurality of 48 percent of Ukrainian men admitting they are not prepared to fight.

These remarks by Putin are only the latest signal that Moscow is ready to enter talks. Putin similarly told Tucker Carlson in February several times that Russia was “ready” to negotiate. More importantly, three separate reports in the New York Times, Bloomberg and Reuters have revealed behind-the-scenes overtures by Moscow, reportedly as early as last September, to Washington for peace talks, which the Biden administration has so far not acted on.

We can’t know for sure if Putin’s remarks are serious until they’re tested in negotiations. But that doesn’t give journalists and commentators free rein to mislead the public that they don’t exist, all for the purpose of undermining the possibility of peacefully ending a war that more and more Ukrainians don’t want to fight in.