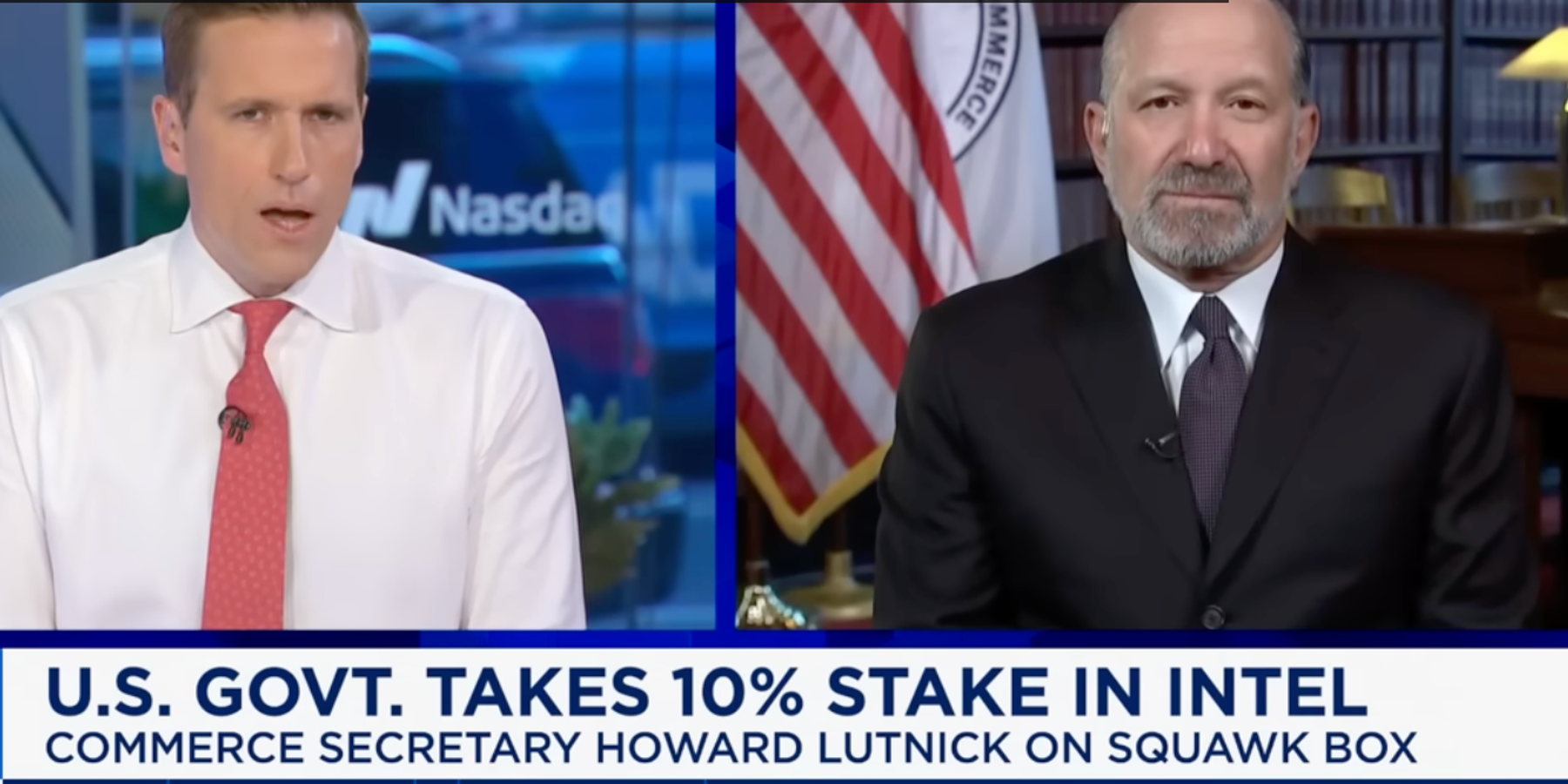

The U.S. arms industry is highly consolidated, specialized, and dependent on government contracts. Indeed, the largest U.S. military contractors are already effectively extensions of the state — and Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick is right to point that out.

His suggestion in a recent media appearance to partially nationalize the likes of Lockheed Martin is hardly novel. The economist John Kenneth Galbraith argued for the nationalization of the largest military contractors in 1969. More recently, various academics and policy analysts have advocated for partial or full nationalization of military firms in publications including The Nation, The American Conservative, The Middle East Research and Information Project (MERIP), and The Seattle Journal for Social Justice.

While perhaps unexpected from the current administration, full or partial nationalization of the largest military contractors is a reasonable policy proposal worthy of serious debate. One benefit of some degree of public ownership is that it could significantly reduce the arms industry’s influence-peddling activities, particularly congressional lobbying. With a direct stake in a military firm, the government would have greater leverage to guide how a firm does business — like, for example, how much it spends on internal investment versus congressional lobbying.

Year after year, industry lobbyists secure legislative victories to raise national security spending and reduce Pentagon contract oversight. As a result, the arms industry has cultivated numerous tools to legally price gouge the Pentagon on military contracts. Contractors enjoy intellectual property rights to weapon systems developed with public funds, guaranteeing maintenance contracts for the duration of a weapon system’s life cycle — a rich revenue source given that maintenance accounts for about 70% of a weapon system’s life cycle cost, on average. It is for this reason that the military’s right to repair its own equipment is contentious.

Members of Congress working to rein in Pentagon waste face serious political headwinds. The arms industry spent nearly $151 million on lobbying and over $43 million on political contributions in 2024. As a result, the leaders of the armed services committees — which draft the annual defense policy bill – are among the highest recipients of arms industry funds in Congress. Their respective policy priorities largely align with industry’s push to reduce Pentagon contract oversight and more broadly, forever change the way the Pentagon buys weapons – to the financial benefit of industry executives and their shareholders.

To put it simply, the arms industry has the U.S. government wrapped around its finger. So while contractors do not need more taxpayer dollars to carry out their Pentagon work, a government stake in Lockheed Martin today could be cheaper than several more decades of industry bilking the government. After all, military contractors increased cash paid to their shareholders by 73% from 2010-2019 versus 2000-2009, all while decreasing spending on research and development and capital investment.

Meanwhile, evidence of industry price gouging the military abounds. Still, contractors cry wolf to Congress and lawmakers come running to pad their bottom lines, aided by trusty industry lobbyists — who some years, outnumber members of Congress on Capitol Hill.

Nationalization is by no means a silver bullet to eradicate Pentagon waste, to say nothing of unnecessary weapons production driven by strategic overreach. I will be making the case for nationalization in greater detail in an upcoming paper at the Stimson Center. Depending on how it’s carried out, partial public ownership could incentivize government officials to cash in on public service even more nakedly than they already do by moving through the revolving door or trading stocks in military firms.

So how the government goes about nationalizing military contractors has direct bearing on the government’s ability to realize its benefits. Analysts can capture this nuance even if they disagree with this particular administration’s interest in or approach to nationalization.

To put a finer point on the question of nationalization, however, it is vile that profit motive for arms production has any impact on the defense policymaking process. National defense is itself a public good, and one of the core functions of government. Full nationalization should be on the table, but even partial nationalization could help curb the financial incentives for arms production. Policymakers would have greater reason to more firmly ground their spending and acquisition decisions in realistic threat analysis — as well as public interest in avoiding both war and Pentagon waste.

- Navy Admiral’s bribery charges expose greater rot in the system ›

- RTX (ex-Raytheon) busted for ‘extraordinary’ corruption ›