As Secretary of State Marco Rubio visits the Caribbean this Wednesday, the region's leaders are threading the needle between standing up against threats to their national interests and safeguarding their need for trade, aid, and remittances from their powerful neighbor to the north.

Rubio's upcoming trip to Jamaica and the small, oil-rich countries of Guyana and Suriname will include high-level engagements focused on the rapidly deteriorating security situation in Haiti, the escalating border crisis between Guyana and Venezuela in the disputed Essequibo region, and the rising influence of China in Caribbean trade and political relations, among other issues.

The visit comes weeks after Suriname's foreign minister Albert Ramdin became the first Caribbean leader ever elected to lead the Washington-based Organization of American States (OAS), beating out Rubio's preferred candidate, Paraguay’s foreign minister Ruben Ramirez, and marking a shift away from the U.S.-aligned posture of the OAS's current secretary general, Luis Almagro.

It also comes as Caribbean heads of state have pushed back against an announcement by Rubio to deny entry to foreign officials determined to be contracting Cuban doctors, with nearly all regional leaders vehemently rejecting the administration’s allegations of forced labor and insisting they would rather give up their U.S. visas than jeopardize their public health systems' cooperation with Cuba, the largest Caribbean island.

On Friday, the 15-member Caribbean Community (CARICOM) convened an emergency meeting in anticipation of Rubio’s arrival, which stems from an invitation by the bloc’s president — Barbados’ Prime Minister Mia Amor Mottley, with whom Rubio will meet in Kingston — for President Trump to visit the region. In late February, the State Department’s Special Envoy for Latin America Mauricio Claver-Carone confirmed that he and Rubio would visit sometime in March, holding preliminary talks with Caribbean leaders in Washington amid Ramdin’s OAS election.

Speaking to reporters on Tuesday, Claver-Carone, the architect of “maximum pressure” sanctions against Cuba and Venezuela during Trump’s first term, said the region’s big opportunity is energy security, hoping U.S. oil investment can counter what he referred to as the “extortive” and “corrupt” Petrocaribe initiative developed by Venezuela in the prior decade.

While most policymakers regard the Caribbean as little more than a sunny destination for tourism, it is frequently referred to by security analysts as the United States’ “third border,” a front line in the hemispheric fight against drug and arms trafficking, according to Eric Jacobstein, a Biden administration official responsible for U.S. policy toward the region, writing in the Miami Herald on Monday.

The U.S. is by far the Caribbean's largest trade partner and provider of foreign assistance, and many islands have considerable percentages of their populations living in the U.S., which makes Trump's proposed travel ban — potentially affecting numerous Eastern Caribbean nations — another major threat to island economies dependent on remittances sent from the diaspora.

Ironically, St. Lucia and St. Kitts and Nevis, two of the countries on the leaked draft list, are, together with St. Vincent and the Grenadines, among the last few nations worldwide that have maintained full diplomatic recognition of Taiwan — a U.S. priority in the region — despite also being members of ALBA, the leftist regional alliance led by Cuba and Venezuela.

Yet the U.S. has no diplomatic presence in those countries, Jacobstein argues, urging Rubio to establish at least two new U.S. embassies in the Lesser Antilles to curb Chinese influence — as the Biden administration did in the Pacific Islands — despite announcements by the Trump team that it intends to reduce Washington’s diplomatic footprint worldwide.

Jacobstein also suggests Rubio sustain security assistance through the Caribbean Basin Security Initiative and maintain support for Haiti’s Multinational Security Support mission, which has suffered cuts, despite promised exemptions, as a result of Trump’s foreign aid freeze.

For Caribbean leaders, the prospect of mass deportations to Haiti of hundreds of thousands of migrants who have either had their temporary protected status rescinded or humanitarian parole terminated is also a major concern, potentially compounding the dire and deteriorating economic and security situation on the ground.

Moreover, recent announcements to revoke oil licenses to U.S. and European firms operating in Venezuela and impose 25% tariffs on countries importing Venezuelan oil could derail Trinidad and Tobago’s major natural gas project in Venezuelan territorial waters. It is being developed with oil giant Shell and was given the green light by Biden’s Treasury Department in 2023.

In Jamaica, Rubio is expected to meet with Trinidadian Prime Minister Stuart Young, who was previously in charge of the project and is certain to raise the Dragon gas field and request a license extension to continue exploration and commence production by 2028.

In Guyana — a country with less than one million inhabitants that has garnered significant attention in U.S. energy, defense and policy circles since it began extracting its offshore oil reserves in 2019 with the help of ExxonMobil — Rubio will meet with officials who have spent considerable resources lobbying Washington for greater attention in recent years.

Last month, Trump’s first-term ambassador to the OAS and nominee for the State Department’s top Latin America post, Carlos Trujillo, registered with the Department of Justice as a foreign agent for Guyana’s foreign ministry through his firm, Continental Strategy LLC, to help the country “increase U.S. trade and investment” and “enhance Guyana’s profile in the United States.”

Trujillo, a Cuban-American former Florida state representative with close ties to Rubio and Trump’s re-election campaign, will be compensated $300,000 for the six-month contract.

But even as Guyanese president Irfaan Ali has cultivated strong ties in Washington, aided by his intimate relationship with a U.S. oil major, other Trump policies have become a significant cause for concern, according to Bloomberg. At the emergency CARICOM meeting Friday, Ali pushed back on reported plans to fine Chinese-linked vessels entering American ports, arguing it could disrupt global shipping and increase the cost of inputs for Caribbean energy production.

He also rejected the proposed visa restrictions over collaboration with Cuba’s medical program, saying, “I don’t see abandoning Cuba as part of this equation.”

Barbados’ Mottley, for her part, argued that her country couldn’t have gotten through the COVID-19 pandemic without Cuba’s doctors, saying they are paid as much as local professionals, while Vincentian Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves, whose government has played a key role in diffusing tensions between Venezuela and Guyana over the contested Essequibo border zone, said, “I would prefer to lose my visa than have 60 poor and working people die,” in reference to hemodialysis patients under Cuban care.

These predicaments have led leaders to walk a fine line between defiance and acquiescence to U.S. ultimatums, particularly in Suriname, “a Trump success story,” according to Claver-Carone, who claims U.S. support for an IMF adjustment program helped get the country out of its “China debt trap” and secure a $10 billion French-U.S. offshore oil and gas deal.

As the small Caribbean nations brace for the impacts of the Trump administration's energy, trade, immigration, and deportation policies, they are also, as a bloc, standing up for their shared interests — with their level of success bound to have important implications for regional stability and prosperity over the next four years.

- With Rubio, Waltz, a harder line on Latin America looms ›

- It's time to normalize relations with Venezuela ›

- Haiti's crisis deepens as foreign troops struggle to curb violence ›

- The elusive Chinese boogeyman in Latin America ›

- Is Rubio finally powerful enough to topple Venezuela's regime? | Responsible Statecraft ›

- After ousting Maduro, Trump and Rubio put Cuba on notice | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Rubio: We can’t rule out more military force in Venezuela | Responsible Statecraft ›

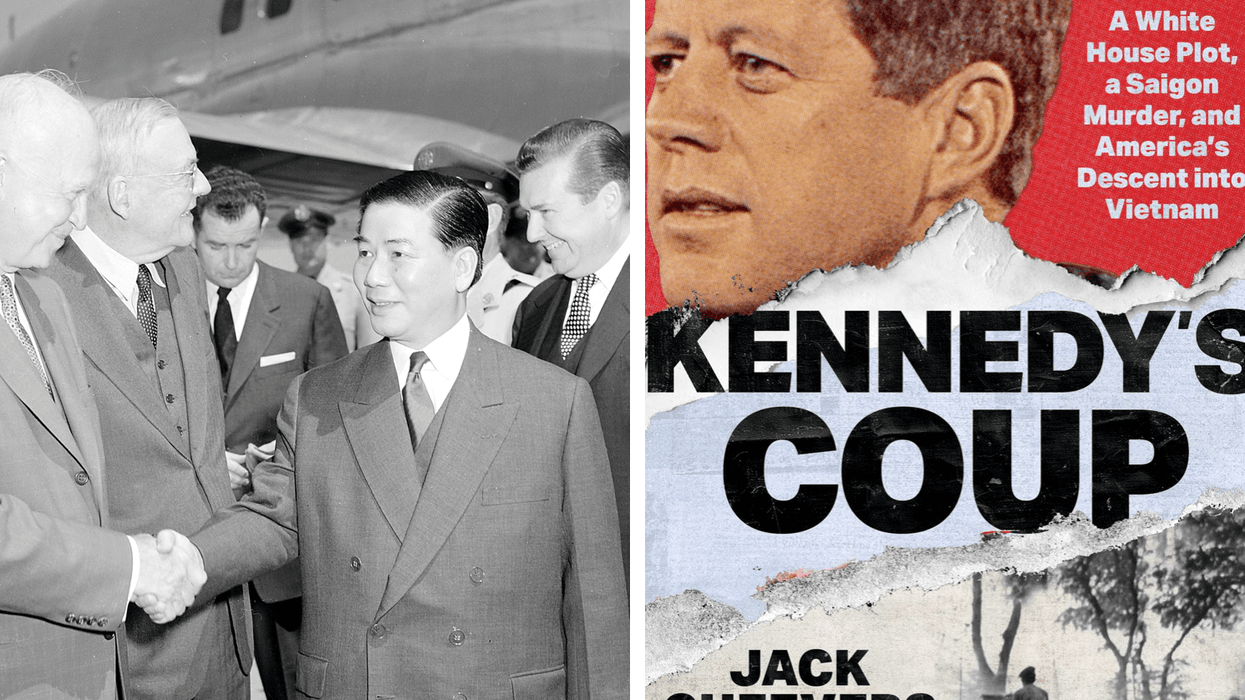

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)

President John F. Kennedy and Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. in 1961. (Robert Knudsen/White House Photo)