With not just one — but two — carrier battle groups now steaming in circles somewhere off the coast of Oman out of the range of Iranian missiles, we are all left with the head-scratching question: what is it, exactly, that the United States hopes to accomplish with another round of air strikes on Iran? Trump hasn’t told us.

The latest crisis du jour with Iran illustrates the strategic swamp willingly stepped into not just by Donald Trump but his predecessors as well. The swamp is built on a singular and hopelessly misguided assumption: that the use of force either by stand-off, limited strikes from 12,000 feet or even invasions will somehow solve complex political problems on the ground below. The United States today sits shivering, gripped with this runaway swamp fever — with no relief in sight.

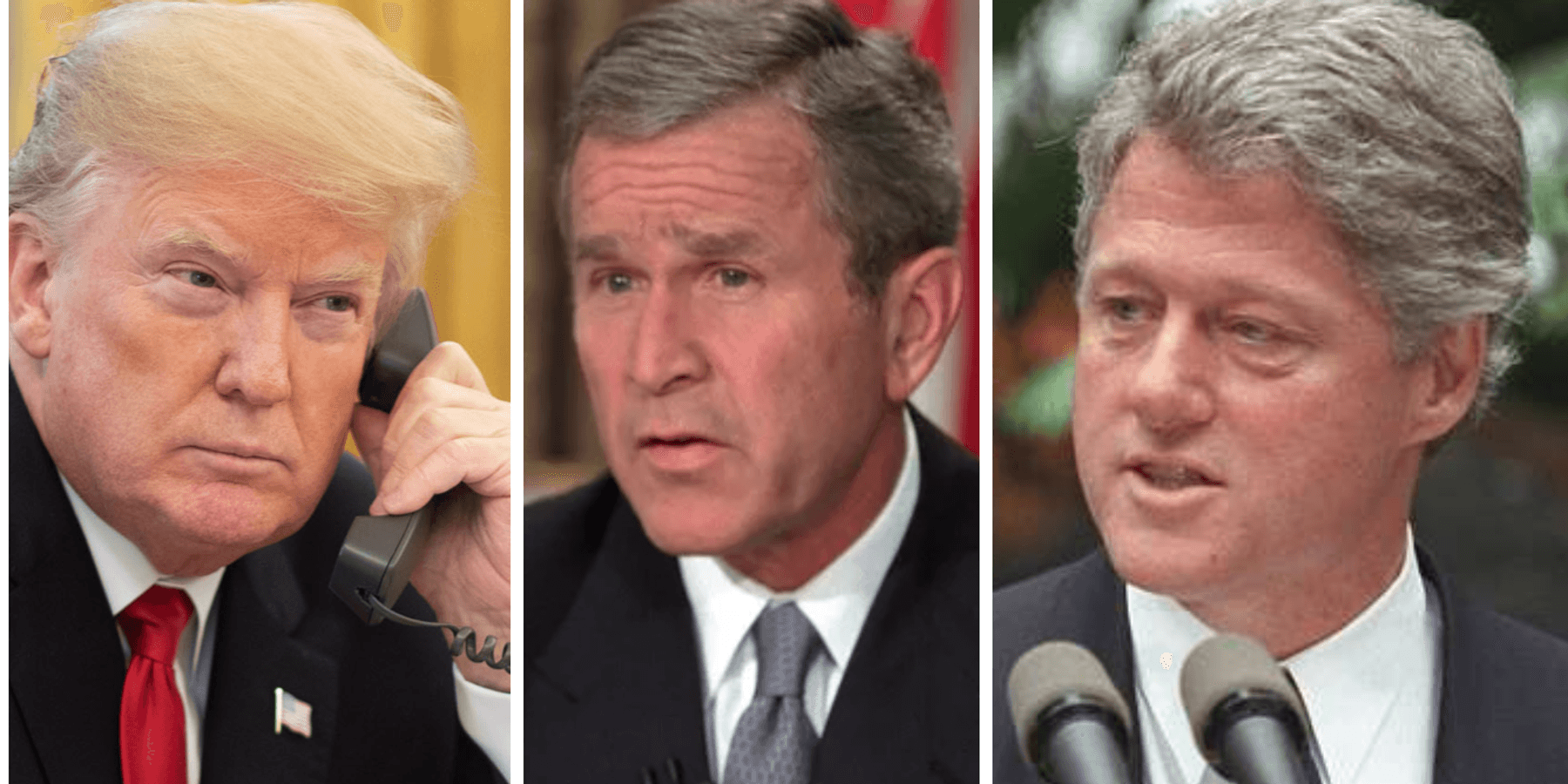

It would be easy to write this off as uniquely Trump.Truthfully, Trump merely provides only the latest example of a political leader showing little capacity to think through how the use of force can achieve political objectives that, in theory, should make the country stronger relative to its adversaries, more prosperous, and safer.

In fact, recent history demonstrates the absence of chief executives capable of such straightforward calculations.

If anything, the late 20th and 21st centuries demonstrate the complete breakdown in strategy and strategic thought that could have guided the country’s leaders into making sensible decisions on whether and in what circumstances to loosen the holster and start blasting away. Instead, all that we’ve seen is a reflexive reach for that holster that seems to become easier over time — despite the clear lack of any achievable positive results for the country. The era remains littered with America’s destructive failures.

What happened and why?

Clearly, the 1990s represented the time when the United States began its descent down the slippery slope of believing that limited standoff strikes and war could achieve political objectives at little cost to itself. During the decade, the Clinton administration repeatedly struck Iraq’s non-existent WMD sites with warplanes and cruise missiles in the vain attempt to force Saddam into coughing up all his supposed weapons.

Who can forget the August 1998 cruise missile strike on the Al Shifa pharmaceutical plant in Khartoum that was supposedly providing chemical precursors to Osama Bin Laden? Never mind that, like Saddam’s non-existent WMD, the plant had provided no such precursors to al Qaeda; instead, the strikes destroyed one of Sudan’s main suppliers of veterinary and human medicines. Washington never apologized but acknowledged later their proof was non-existent.

These miscalculations, however, paled in comparison to the decisions to invade Iraq and Afghanistan in 2001 and 2003, respectively. In both cases, political leaders, seized with the post-9/11 fervor to avenge the attacks and build democracies where none had existed, believed that quick, low-cost operations would re-engineer the politics of both countries. Trillions of dollars and thousands of dead soldiers and civilians later, the United States fled both countries having failed in its myriad missions.

Demonstrating an apparent inability to think through the implications of colossal failures in Iraq and Afghanistan, America’s leaders and their European partners decided in 2011 to rain bombs down on Libya, which eventually led to the death of Libyan leader Moammar Gadhafi and a civil war that persists to this day.

To its credit, the Obama administration sought better political relations with Tehran through dialogue and diplomacy instead of saber rattling and eventually reached an agreement to limit Iran’s nuclear program, an agreement subsequently ripped up by Trump in 2018. President Barack Obama also normalized relations with Cuba, an effort also quickly squelched by Trump when he arrived in the Oval office. But the aforementioned Libya strikes and uptick of the killer drone war was all under his watch, too.

Another instance in this by no means exhaustive list must be the hapless Biden administration’s decision to start bombarding the Houthis in January 2024 in response to their attacks on shipping in the Red Sea. The Houthis initiated their attacks to press Israel to end its slaughter of the Palestinians in Gaza. Somehow, it was believed that the U.S. bombardment would lead to positive results and change the Houthis’ behavior. It continued until March 2025, when President Trump sensibly stopped the attacks, but not until after billions of dollars and U.S. ordinance was expended.

Several strands of continuity that bind these examples together led the country into the swamp. The first of these must be the hubris of political leaders, who clung to the innate belief in American power and exceptionalism. Clearly, a source of that hubris also was rooted in the confidence in its military superiority a — understandable for a country that spends more on its military than almost all of the rest of the world combined. Political leaders believed that a new family of digitized weapons delivered with great accuracy at long distances could pound our enemies into submission without bringing American coffins home.

Last but not least, we mistakenly believed our enemies were weak and we were strong, and that armed confrontations would be shaped by this basic and undeniable fact.

All of these assumptions represented (and continue to represent) a profound misunderstanding of circumstances that framed the pursuit of military dominance as the key instrument of policy.

These strands of continuity and misunderstandings about war and the application of force also collided headlong into the decline in the quality of presidential leadership in the post-Cold War era and, in parallel, a decline in the community of civilians and military alike engaged in strategic studies.

Stated differently, the “bench” of strategic thinkers in government to help inform decision-making on these issues has steadily deteriorated over the last quarter century. The academy shares the blame; it has deemphasized strategic studies in its graduate programs across curriculums. Political science programs at the nation’s hallowed universities push their students into theoretical and quantitative studies; history departments show little interest in military history. Those civilians interested in these areas inevitably get pushed into the D.C.-based think-tank community, which is driven by ideologically-based analysis and fund raising.

Moreover, the ascendance of the neoconservatives in this community demonstrates a disturbing “school solution” focused on using force to solve the various strategic problems facing the country that has helped warp the intellectual landscape in the marketplace of ideas.

On to Tehran

Any sober analysis of America’s confrontation with Iran should tell us that the carrier battle groups can achieve no meaningful or positive political objectives should they be ordered to attack. The United States could order its land forces to somehow invade the country, but is there anyone who believes that such an extreme and unfathomable action would create a favorable outcome with what would be horrific costs?

Yet these considerations apparently remain lost to our political leaders — who cling to misguided beliefs that bombing and war will somehow create favorable outcomes — as undefined as those outcomes might be.

It’s the definition of insanity that stretches back more than a quarter century: expecting different results from the same actions, over and over again.

- Why Arab states are terrified of US war with Iran ›

- If Iranian regime collapses or is toppled, 'what's next?' ›

- Gen Z doesn't have the same hang-ups about Iran as older Americans | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Fury and fanboys: US, world leaders react to US-Israeli war on Iran | Responsible Statecraft ›

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org