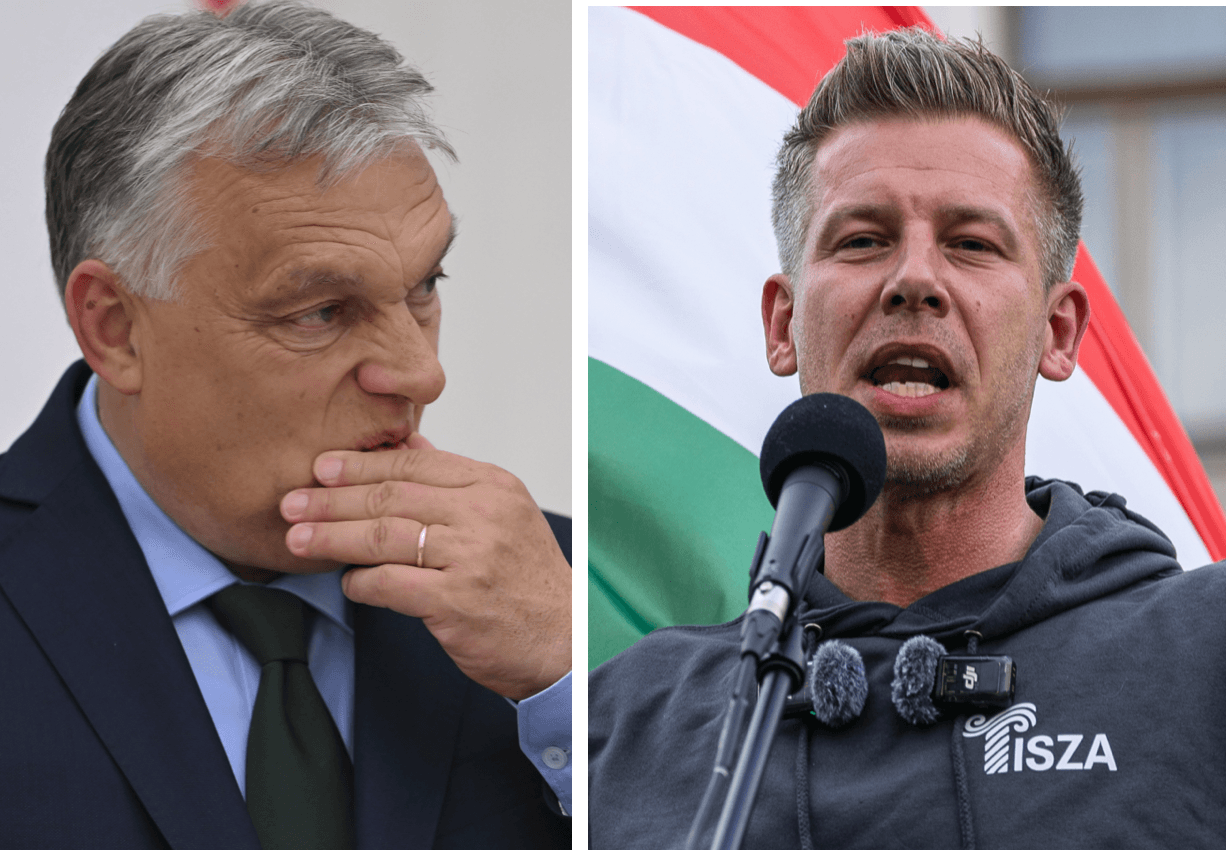

With two months remaining before the April 12 parliamentary elections, Hungary’s Prime Minister Victor Orban and his Fidesz party face by far their toughest challenge since winning power in 2010.

Many polls show challenger Peter Magyar’s Tisza (Respect and Freedom) party with a substantial lead. Orban’s campaign has responded by stressing his international clout, including close relations with U.S. President Donald Trump, and the prominent role he plays among right-populist Eurosceptics in Europe.

Magyar has run an astute campaign, harnessing an anti-incumbent mood. He focuses on social and economic dissatisfaction, as well as Hungary’s estrangement under Orban’s leadership from the European Union’s mainstream.

The Prime Minister is elected by the National Assembly (parliament) following elections. The official campaign period begins in March but it has been intense since mid-January. Hungarian society has become polarized and energized by the first genuinely close race since Orban took office in 2010.

European significance

This election will be a crucial test for Europe’s new right, as Orban has achieved success with sovereigntist, anti-migrant, and traditionalist themes, at odds with much of the EU. An Orban loss could signal flagging momentum for the European populist right, affecting, for example, the French presidential election next year, where the like-minded National Rally party leads in polls.

In a clear demonstration of the significance of this race beyond Hungary, the Orban camp last month released exuberant endorsements from prominent right-wing political figures, including Marine Le Pen, head of France’s National Rally, Alice Weidel, leader of the Alternative for Germany Italian Prime Minister Georgia Meloni Czech PM Andrej Babiš former Polish PM Mateusz Morawiecki Serbian president Aleksander Vučić Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu; and Argentina’s President Javier Milei.

On February 6, President Trump endorsed Orban’s re-election, and Orban has announced plans to come to Washington for a Board of Peace meeting to be chaired by Trump at the end of February. Secretary of State Marco Rubio plans to visit Hungary after taking part in the Munich Security Conference in what will likely be understood as his endorsement.

It’s (mainly) about Ukraine

Orban has staked his re-election on passionate opposition to external pressure on Hungary, personified by Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen. Orban accuses Magyar of being a proxy for Zelensky’s Ukraine and likely to draw Hungary into a devastating war.

To a considerable extent, Orban has made the election a test of public support for an early peace settlement to end the war in Ukraine, and implicitly for U.S. diplomatic efforts to this end.

Orban pledges to stick to his opposition to fund or arm Ukraine and to resist pressure from the EU Commission to bring Hungary into the pro-Ukraine mainstream.

In an escalating war of words with Zelensky, Orban called Ukraine an “enemy” of Hungary, because of Zelensky’s push for a complete ban on all Russian oil and gas imports into the EU. Hungary relies on Russian oil through the Druzhba pipeline, as does Slovakia. Both have been exempted from EU measures to halt these imports, arguing that they have no alternative source. Orban also has accused Magyar of complicity in election interference on the part of Ukraine.

Notably, the recently released election manifesto of Magyar’s Tisza party does not call for Hungarian funding or arming of Ukraine but it does promise better relations with Ukraine and repairing relations with Poland. It opposes any fast-track EU accession for Ukraine.

Magyar focus on corruption, cronyism and mismanagement

Magyar seems to be avoiding a direct challenge to Orban’s stance on Ukraine, emphasizing generational change instead (Magyar is 44 years old; Orban is 62). In essence, the Magyar campaign is an anti-incumbent protest against a very long-serving leader with a lot of baggage.

Magyar was a senior member of Orban’s Fidesz party until 2024 and is the ex-husband of Orban’s former justice minister. He was not the obvious choice of much of Hungary’s fragmented liberal and social democratic opposition. He has built support for having demonstrated the potential to defeat Orban, even if he would share some of Orban’s conservative and nationalist worldviews. To win, Magyar needs to attract some disaffected Fidesz voters.

Magyar seeks to mend fences with the European Commission, largely as a means to boost Hungary’s economic performance. He would negotiate with the Commission to unlock some of €18 billion it has withheld from Budapest due to violations of EU laws and norms under Orban’s leadership. The Commission will likely expect Hungary under Magyar to support its approach to Ukraine and Russia, even if Magyar has not publicly offered any such concessions.

Magyar has promised to eliminate corruption, promote judicial independence, and restore independent media. But he would face formidable opponents from within state institutions where leadership will remain in the hands of Fidesz loyalists.

The Magyar camp faces changes in electoral rules which, his supporters claim, favor the incumbent. A very close and contested election could bring disruptive and destabilizing protests. Mutual accusations about foreign interference could result in political instability.

Why it matters

Although a milder version of Orbanism could survive a Magyar victory, Orban’s defeat would be a body blow to the new right’s momentum across Europe. Such an outcome could embolden efforts by some European leaders to stave off any peace settlement not unambiguously favorable to Ukraine and aggravate already tense relations between the U.S., given Trump’s endorsement of Orban, and its NATO allies. Not least, it would embarrass the U.S. president.

On the other hand, European parties of the establishment center-right and center-left might draw encouragement that the new right can be defeated at the ballot box, making it less necessary to quarantine them.

- EU hypocrisy on parade as Netanyahu goes to Hungary without a peep ›

- EU's far left and right coding obliterated by Iran and Israel votes ›