“Barbarism is on the ballot,” columnist George Will declared this week, noting that if the next president doesn’t transform the current policy on Ukraine, which is “so timid, tentative and subject to minute presidential calibrations,” then Russia’s Vladimir Putin’s war could end up being a “great rehearsal” for World War Three.

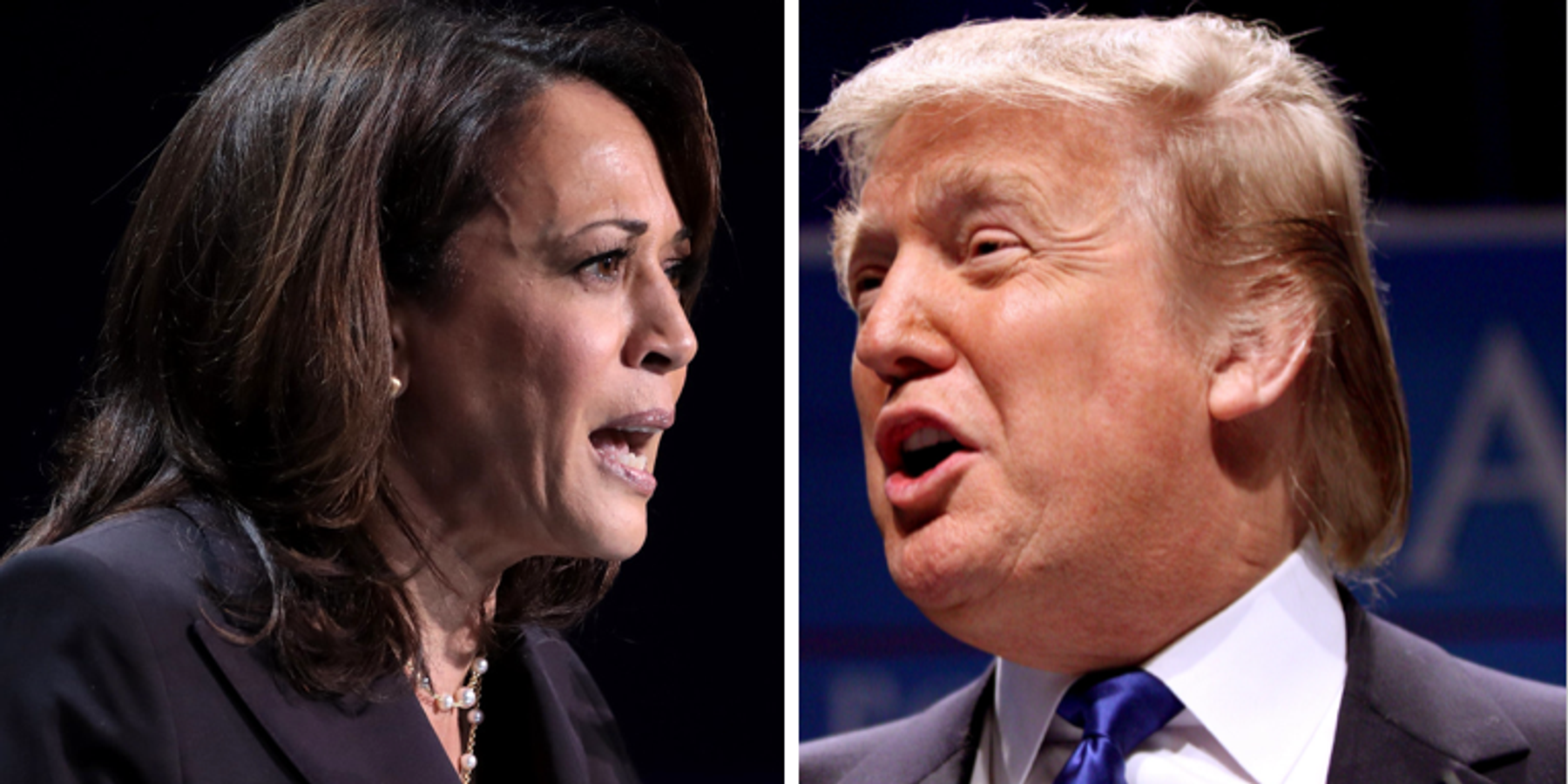

Meanwhile, the New York Times has said that “two different futures loom” for Ukraine depending on the outcome of Tuesday’s election, Kamala Harris or Donald Trump.

Much of this is based on the candidates’ rhetoric, and, in the case of Harris, the Biden Administration’s current policy of supporting Ukraine with weapons and aid for “as long as it takes” to defeat Russia. Harris has suggested she would continue this policy, to “stand strong with Ukraine and our NATO allies,” if elected. She has also accused Donald Trump of being too cozy with Putin and said she would not talk to the Russian president.

For his part, Trump has said he would bring all sides to the table and end the war in a day, and he has been critical of continued U.S aid to Ukraine, which has totaled some $175 billion ($106 billion of which has gone directly to the Ukraine government) since 2022. He has offered no details for how he would end the war or bring the parties together.

But does it matter? In some ways, yes, foreign policy experts tell RS. One side wants to assure that U.S. strategy won’t change, the other advocates for a bold if not abrupt shift that involves a step back from the narrative George Will evinces, that Putin is a barbarian that can only be stopped with more war.

Those same experts say Ukraine is losing, and more weapons and more fighting cannot help. They also point out that official Washington is beginning to realize this too, as is Europe, and a shift toward diplomacy will likely happen no matter who is in the White House come January 2025.

“Ultimately the war in Ukraine will be determined by the balance of power on the ground. This very basic fact often gets lost in conversations about the war. Regardless of whether Kamala Harris or Donald Trump wins tomorrow, the Ukrainians are facing an extremely dire situation at the front, with the Russian offensive continuing to chip away at Ukraine’s defensive lines in Donetsk and its manpower shortages becoming more of a problem every day the war goes by,” says Daniel DePetris, foreign policy analyst and regular Chicago Tribune columnist.

“I don't think the outcome of the election will have a decisive impact on the Ukraine war. Ukraine is losing territory at the fastest rate since the war began, and its main problem is manpower, not lack of weapons,” offers Jennifer Kavanagh, director of military analysis for Defense Priorities.

"After the election, Kyiv will have to shift its strategy regardless of who wins because its current approach is not sustainable,” she adds.

In addition to recruitment problems, Ukraine is suffering from high casualties, low morale, and now desertion. Russia has also sustained massive losses, but it is a much larger country and has yet to fully mobilize due to public pressures against a draft. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy has tried to compensate by asking for more sophisticated, long-range weapons and the ability to fire them further into Russia, but the U.S. has been resistant and is the deciding factor in that request.

“Regardless of who wins, the next American president will face harsh realities in Ukraine that will demand a change from Biden’s present policies. Russians vastly outnumber Ukrainians and produce far more military materiel than both Ukraine and its Western backers,” points out George Beebe, the director of the Quincy Institute’s Grand Strategy program.

“As a result, Ukraine cannot win a war of attrition with Russia, and is headed, sooner or later, toward a general collapse absent either a diplomatic deal to end the war or a U.S. decision to go to war with Russia.”

Meanwhile, as supportive as the European leadership has been, elections across the region, particularly in Germany — Ukraine’s second biggest weapons supplier — have reflected public exhaustion with the war due in major part to its visible economic impacts. Sanctions on Russia have not “crushed” Moscow’s economy or war effort, but have had negative effects on European energy prices.

“Staying the present course would be a formula for Ukraine’s becoming a failed state, with Europe thrown into growing disarray as a consequence,” notes Beebe.

“The war is coming at a high price for all involved,” offers John Gay, director of the John Quincy Adams Society, noting that whoever wins on Tuesday, Europe has to start making major decisions for itself — in part how much it can do for its own security if and when U.S. support begins to recede.

“Europe needs to be able to deter Russia and defeat a Russian invasion with little direct U.S. support,” he says. “Is the current NATO target of 2 percent of GDP for defense adequate for that?”

So what are some of the differences each candidate may bring to the Oval Office in January?

“I am not convinced that Harris will buck the national security establishment, her advisors, and Democratic leaders in Congress by suddenly pushing for an end to the war in Ukraine. I expect more of the same if she wins,” charges former CIA analyst Michael DiMino.

“A Trump Administration will probably have a much bigger impact on the future trajectory of the conflict. But as I always say: personnel is policy,” he adds.

"If Trump wins, there will be an early push for a peace settlement. He will not meet all Russia's demands, but Russia may still provisionally accept, in the hope that Ukraine (and Poland) will reject them, and Trump will then abandon Ukraine,” says Anatol Lieven, head of the Quincy Institute’s Eurasia program.

“We will then have to see whether Trump and his administration have the skill and stamina to conduct a complicated and fraught negotiating process.”

“If Harris wins,” Lieven adds, “she will also aim for peace, but the process will be much slower and more hesitant, the terms offered Russia will be much worse, and Russia will go on wearing down the Ukrainians in the hope of a crushing military victory.

“In this case, everything will depend on the progress of the war on the ground, and whether in order to try to ward off a Ukrainian collapse, Harris would be willing to escalate drastically,” says Lieven.

“Anybody who says he knows what Donald Trump would do about Ukraine is lying or delusional. Trump himself doesn’t know,” says Justin Logan, director of Defense and Foreign Policy Studies at the Cato Institute.

“Kamala Harris would be led by her advisers, who will likely come from the Brookings (Institute) cafeteria school of foreign policy,” he adds. “Trump would be heavily influenced by his own advisers. The question is who those advisers will be.”

At the very least, Trump and Harris should be sufficiently allergic to policies that could escalate the war in ways that would make peace impossible.

“No U.S. president, Republican or Democrat, should be eager to shovel tens of billions of dollars a year, forever, into the Ukrainian furnace,” says Gay. “Both sides are escalating the conflict in new ways — bringing in North Korea, seeking looser targeting rules, and more. No U.S. president should be eager to see how far escalation can go before the conflict spreads beyond Ukraine.”

- Trump tells CNN town hall: 'I want everyone to stop dying' in Ukraine ›

- Harris' aversion to talks with dictators is more Bush than Obama ›

- Debate: On Gaza & Ukraine, Harris and Trump put 'America last' ›

- Diplomacy Watch: Ukraine and Europe brace for Trump | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Europe already 'Trump proofing' Ukraine war aid | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Trump has a mandate to end the Ukraine War | Responsible Statecraft ›

- With Putin, Trump's 'art of the deal' is put the the test | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Diplomacy Watch: Trump and Zelensky announce Minerals deal | Responsible Statecraft ›