A draft proposal to authorize the use of U.S. military force against drug cartels is currently floating around Congress and the White House, according to a recent New York Times report. Although an official version of the proposal has yet to be released, publicly available information suggests that it could be used to justify U.S. military intervention in at least 60 countries.

The U.S.-led “War on Drugs” has escalated rapidly over the last month: after the White House signed a secret directive authorizing attacks on Latin American drug cartels, the U.S. built up its military presence in the region and began conducting a series of deadly airstrikes on alleged drug-smuggling civilian boats in the international waters of the Caribbean. Human Rights Watch called the strikes “unlawful extrajudicial killings.”

How far Washington should go in its new counternarcotics campaign has been a source of controversy within the Trump administration. When the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) proposed the use of the U.S. military to attack cartels within Mexican territory during a White House meeting earlier this year, officials from the Defense Department and other agencies reportedly objected, in part because the executive branch lacked sufficient legal authorization to do so.

An “Authorization for Use of Military Force” (AUMF) is the instrument most often used to provide legal justification for military hostilities today. AUMF legislation passed in response to the 9/11 attacks laid the groundwork for a “Global War on Terror” that included targeting many suspects who had nothing to do with 9/11. Because of its extremely broad language, the 2001 AUMF has since been used to justify military interventions in at least 22 countries.

A proposal reportedly brought forth by Rep. Cory Mills (R-Fla.) for a new AUMF aimed at “narco-terrorists” began circulating around Washington last week. Apparently modeled on the 2001 AUMF, Mills’ new AUMF is similarly broad: although it only lasts for five years, the authorization does not identify specific targets and contains no geographic restrictions.

In comments given to the Times, Harvard Professor Jack Goldsmith described the proposal as “insanely broad,” essentially “an open-ended war authorization against an untold number of countries, organizations and persons that the president could deem within its scope.” The version of the AUMF that has been attributed to Rep. Mills would give the president the ability to use “all necessary and appropriate force against those nations, organizations or persons the President determines are designated narco-terrorists,” including those who provide financing or support to narco-terrorists.

Earlier this year, the White House added a long list of Latin American drug cartels to the national “Foreign Terrorist Organizations” (FTO) list. Although the full text of Mills’ AUMF hasn’t been confirmed, under his reported proposal, the president could have the authority to wage war against any of these organizations, regardless of where they are operating. Given the highly globalized nature of the drug trade and the contested definition of who is included within “drug cartels,” this could include U.S. military action in dozens of different countries. Based on what is known about it so far, Mills’ proposal would leave “a large amount of discretion in the hands of the executive to make determinations about who ‘counts’ within the scope of targeting,” said Elizabeth Beavers, assistant professor of law at Widener University’s Delaware Law School.

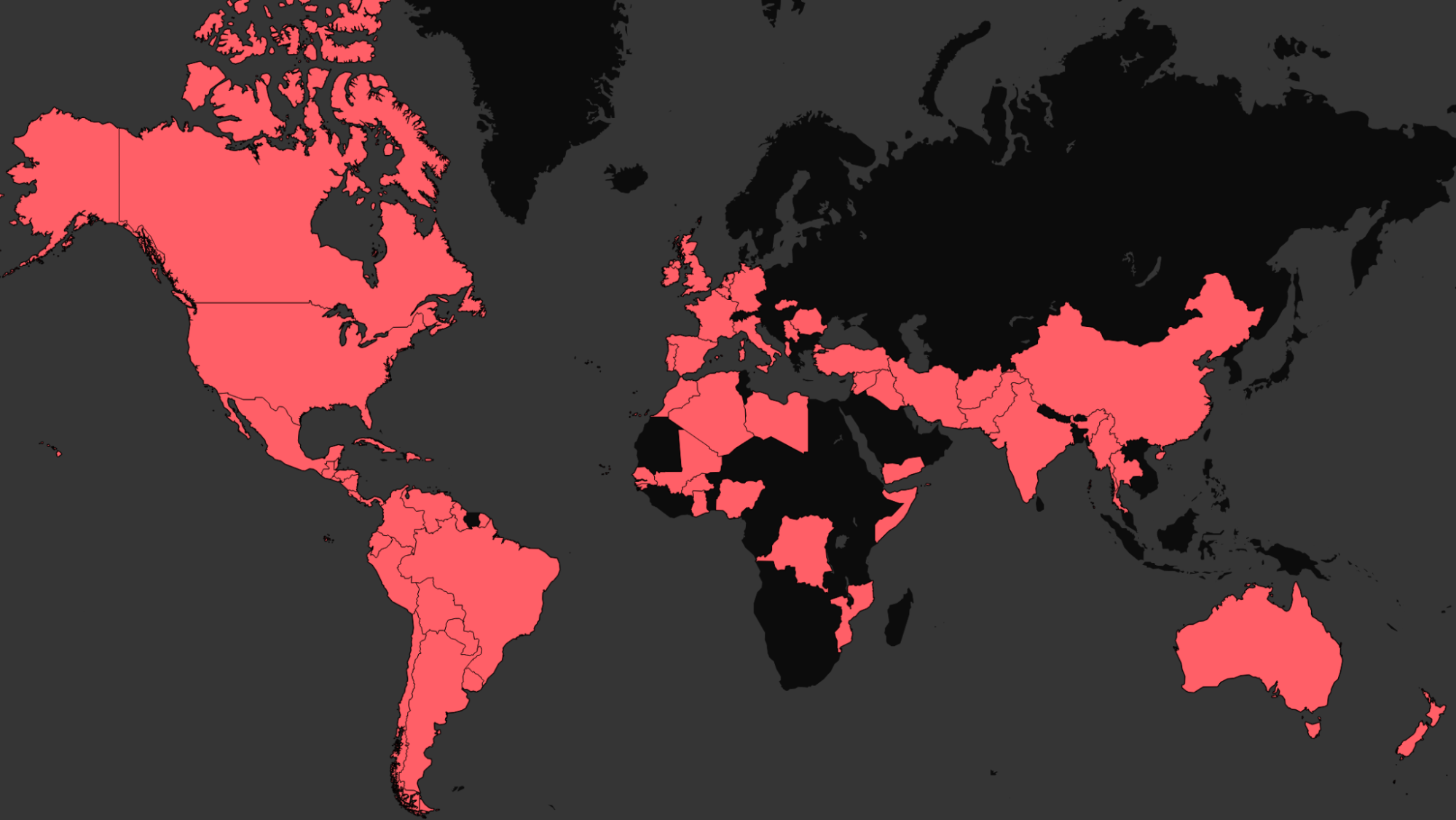

The Sinaloa Cartel, for example, designated as a FTO by the Trump administration in February, operates in “at least 47 countries,” according to the DEA. In a five-part series of articles on the “foreign policies of the Sinaloa Cartel and CJNG [another Mexican cartel]”, scholar Vanda Felbab-Brown lists some of the countries that are allegedly involved in the Sinaloa’s activities: Albania, Australia, Belgium, Cape Verde, Chile, China, Colombia, the DRC, Ecuador, France, Germany, Ghana, Guinea-Bissau, Ireland, India, Italy, Mali, Morocco, Mozambique, the Netherlands, New Zealand, the “Northern Triangle” nations of Central America, Nicaragua, Nigeria, Peru, Portugal, Romania, Senegal, Serbia, Slovakia, Spain, and the UK. Other countries with Sinaloa Cartel activity include Belize, Canada, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Guyana, Panama, and Thailand.

If the proposed AUMF had targeted the Sinaloa Cartel alone, it could theoretically authorize U.S. military interventions in at least 42 nations. But this is only one of many cartels that has been designated as a terrorist organization by the Trump administration. War against the CJNG would add Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay, Turkey, Uruguay, and Venezuela to the list. Cartels like Tren de Aragua have an established presence in Costa Rica. Meanwhile, the Trump administration designated several more countries as high-priority drug transit routes, specifically arguing that our “assistance” was “vital to the national interests of the United States” in Afghanistan, Bolivia, Colombia, Myanmar, and Venezuela.

Taken together, the combined forces of the proposed AUMF and the terrorist designations for cartels could allow the U.S. president to intervene in almost every nation in the continental Americas. Taken literally, the AUMF might even be abused to justify hostilities within the United States, as the terrorist-designated MS-13 gang was created in Los Angeles and maintains extensive operations throughout the U.S. In practice, however, this is highly unlikely.

“There are still a whole host of constitutional protections against extrajudicial targeting of persons within the U.S. that an AUMF doesn't just sweep away,” said Beavers. Still, this assumes that the president would be willing to abide by these protections. “This entire conversation about lawfulness rests entirely on what the other branches of government, including the courts, are willing to do about such violations,” she added.

U.S. authorities have long tried to expand their power by blending together the War on Drugs and the War on Terror, often using the controversial idea of “narco-terrorism” to make the connection. In 2011, the DEA claimed that 39% of Foreign Terrorist Organizations had “confirmed links to the drug trade.” This newly-proposed AUMF could therefore be applied to many traditional terrorist organizations, including al-Qaeda, Hezbollah, and the Taliban. This means the AUMF could provide additional authorities (on top of those from prior AUMFs) for the U.S. to involve itself in the countries where these groups operate. Such a list would likely include the Taliban’s involvement in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Hezbollah’s involvement in Lebanon, and a long list of countries alleged by the U.S. government to have al-Qaeda affiliates: Algeria, Burkina Faso, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Mali, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen.

The U.S. has also long accused the Colombian National Liberation Army (ELN) of narco-trafficking. Because of Cuba’s involvement in negotiations between the ELN and the Colombian government, Washington has insisted upon the classification of the island nation as a “State Sponsor of Terrorism.” Thus, the White House could theoretically use this proposed AUMF to engage in military hostilities in Cuba. Similarly, U.S. attempts at linking Venezuela’s government leadership with an alleged “Cartel of the Suns” could be used to engage in a war against the Venezuelan military, not just the cartels alleged to operate within the nation.

Adding together all of these potential applications of the proposed AUMF, the bill would create justifications for the White House to engage in offensive military activity in more than 60 nations. While there’s currently no indication that Congress is eager to take up, let alone pass, an extremely broad new military force authorization, if it were to become law, it would fully merge two of the largest policy failures in U.S. history — the War on Drugs and the War on Terror — into one singular concept that could expand armed conflict throughout the entire Western hemisphere and beyond.

- 20 years after Iraq War vote, Barbara Lee is fighting to end the War on Terror ›

- A cartel war is an insane way to address fentanyl crisis ›

- How presidents used the 2001 AUMF to justify wars unrelated to 9/11 ›

- Why we need to take Trump's Drug War very seriously | Responsible Statecraft ›

- Aargh! Letters of marque would unleash Blackbeard on the cartels | Responsible Statecraft ›