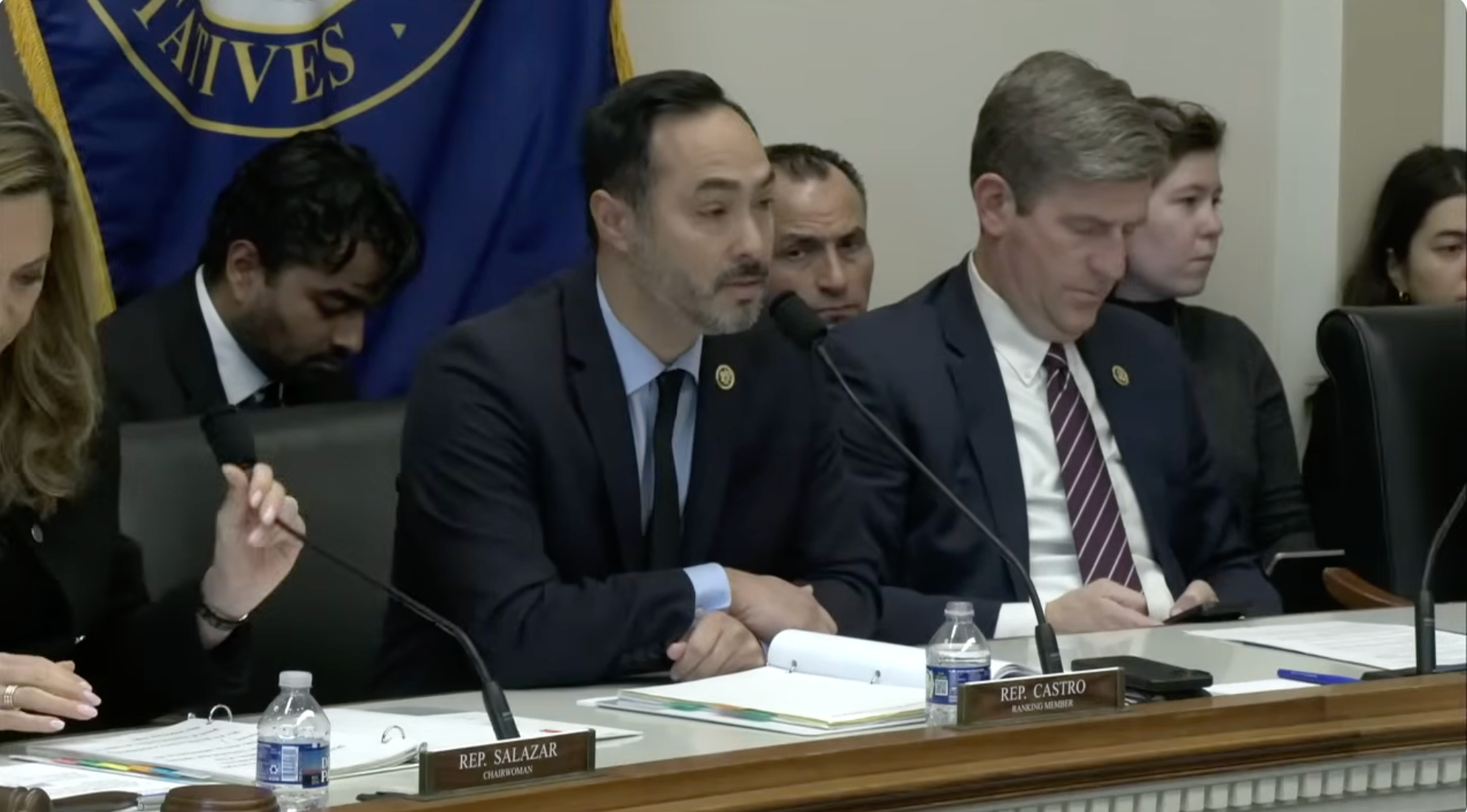

At a congressional hearing Thursday, Rep. Joaquin Castro (D-Texas) did something that members of Congress rarely do; he called out a conflict of interest from an “expert” witness.

“I think it’s fair to consider whether there are conflicts of interest being presented here today,” said Castro.

Castro’s comments were directed towards Carlos Trujillo, who testified during a hearing on election integrity in Honduras and allegations that the center-left incumbent LIBRE party is trying to steal the November 30 presidential election.

“If they do steal the election and go down that road…it has to end without any credible democratic actor recognizing the legitimacy of the regime,” Trujillo warned the lawmakers on the House Foreign Affairs Western Hemisphere Subcommittee.

Trujillo, a former U.S. ambassador to the Organization of American States, told Congress that Hondurans' “hope for saving their democracy” is “vested in a hearing like this,” pointing to the U.S.’s ability to impose sanctions on the government.

However, what Trujillo failed to mention is that his lobbying firm, Continental Strategy LLC, worked for at least four clients tied to Honduras this year, including financial institutions owned by some of the country’s richest men, a port company, and Honduras Próspera, a controversial private charter city in Honduras backed by Silicon Valley billionaires. Altogether, these Honduran clients paid Trujillo’s firm at least $670,000 this year alone, and many of the entities that it represents have a clear stake in ousting the LIBRE party in favor of a more business-friendly administration.

This would have gone undisclosed, if Castro — the committee's ranking member — had not raised the question about Trujillo’s status as a paid lobbyist for Honduran business interests opposed to the LIBRE party. That revelation led to a tense exchange during Thursday’s hearing.

CASTRO: You and your firm have significant corporate clients in Honduras who are actively working against the sitting government, is that correct?

TRUJILLO: That is not correct.

CASTRO: You have clients in Honduras.

TRUJILLO: I do have clients in Honduras.

When Castro asked whether Trujillo had spoken with his clients about the hearing, the subcommittee’s chairwoman, Florida Republican Maria Elvira Salazar (R-Fla.), interrupted:

SALAZAR: Ambassador Trujillo may have many clients in Honduras but that does not mean that he does not want the best outcome on November 30th, so I think we should just concentrate on finding out what’s really happening right now and how we can preserve the integrity of those elections.

CASTRO: Chairwoman, I never interrupted your time and you’ve never interrupted my time and these are fair questions about a witness especially when the witness talked about conflicts of interest of others in Honduras. I think it’s fair to consider whether there are conflicts of interest being presented to us today and so that's why I asked him about the clients that he represented, including Prospera which was very controversial in Honduras, which was fighting with the government there, involved in litigation and later arbitration.

Watch the full exchange:

Trujillo’s clients, of course, do have interests of their own. In particular, they have close ties to former right-wing President Juan Orlando Hernández, who, after being reelected in 2017 in a process declared fraudulent by the OAS, among other observers, pursued a set of pro-business policies benefiting Trujillo’s clients. As the U.S. ambassador to the OAS, Trujillo met with and praised Hernández — who is now serving a 45-year federal prison sentence for facilitating and profiting from drug trafficking to the U.S. — for his cooperation with Washington in the fight against organized crime.

One of Trujillo’s clients, Grupo Ficohsa, a company led by one of the country’s richest men, Camilo Atala Faraj, has paid Trujillo’s firm $120,000 so far this year. Atala Faraj maintained close ties — and his bank lent millions of dollars — to the former president, whose economic policies favored large conglomerates like Ficohsa. Another of Trujillo’s clients, Banco Atlántida, is a bank whose founding president, Gilberto Goldstein Rubenstein, was a long-time leader of Hernández’s National Party. The firm has paid Trujillo $415,000 thus far in 2025.

Trujillo’s clients have long opposed the ruling LIBRE party of President Xiomara Castro.

Honduras Próspera, which gave Trujillo’s firm $105,000 since October 2024 before the contract was terminated last July, is currently embroiled in a multi-billion dollar dispute with the Castro administration over its policies to rein in unregulated special economic development zones (ZEDEs) that had been greenlit by Hernández.

Over the past three years, Honduras Prospera has lobbied D.C. lawmakers in an effort to portray the project as a bulwark against socialism in Latin America. Many of these lawmakers have since called for sanctions if President Castro continues to oppose the ZEDEs legislation, while others have inserted language ratcheting up the pressure into the annual State Department funding bills.

Banco Atlántida, which had been granted concessions for 14 major hydroelectric projects under Hernández’s administration — only to be taken away soon after by Castro’s in response to popular protests by nearby communities — has since been implicated in the creation of a new, explicitly anti-LIBRE media outlet, ICN Digital, which regularly gives the bank free publicity.

After the 2009 military coup in Honduras that ousted Castro’s husband and LIBRE party leader Manuel Zelaya as president, Grupo Ficohsa paid lobbyist Lanny Davis to help legitimize the provisional government of Roberto Micheletti in Washington. More recently, it hired lobbyists to oppose legislation supported by the LIBRE party that would have conditioned U.S. military aid and international loans to the country on investigations into grave human rights violations carried out by Hernández’s security forces.

Thursday’s hearing underscored concerns about the U.S. intentionally tipping the scale of Honduras’ upcoming elections one way or the other through the purportedly independent expertise provided by witnesses called to testify before the subcommittee.

“I think it’s fair to consider whether there are conflicts of interests being presented to us here today, so that’s why I asked him about the clients he represented,” Castro said, defending his comments. ”I think folks need to know that, I think that’s important.”

When non-governmental witnesses testify before Congress, they are required to fill out a disclosure document designed to reveal conflicts of interest, known as a “Truth in Testimony” form. However, there is no question on the form that requires witnesses to disclose organizational funding from private companies that may have a vested interest in the committee’s deliberations, leaving Congress in the dark on conflicts of interest simply because they didn’t ask.

Many witnesses also choose to exploit a loophole that allows them to testify in a “personal capacity.” In other words, even if they happen to work as a lobbyist and represent foreign government or corporate clients, they are not required to disclose that information.

When Trujillo testified on Thursday, he did so in a “personal capacity” and did not disclose any of his foreign clients.