On Sunday, Secretary of State Antony Blinken signaled that the U.S. would not stop Ukraine from using American-made, long-range missiles to attack targets inside of Russia.

“In terms of their targeting decisions, it’s their decision, not ours,” Blinken told ABC before adding that “we haven’t encouraged and we haven’t enabled any use of weapons outside of Ukraine’s territory.”

Blinken’s comments, which come on the heels of reports that the U.S. will soon send long-range missiles to Ukraine, are the latest example of Washington’s slow-moving approach to breaking through Russian red lines in the conflict. President Joe Biden had long argued that providing Kyiv with Army Tactical Missile Systems, better known as ATACMS, would be a bridge too far for the Kremlin, but that view has apparently lost purchase as Moscow has failed to back up its threats of escalation.

Meanwhile, Russian hawks have grown increasingly frustrated with President Vladimir Putin, with many prominent figures arguing that the Russian leader must do more to deter American involvement in the war. This increase in pressure could push Putin to make a drastic move, according to George Beebe of the Quincy Institute.

“The danger is that as Washington grows more confident that it need not fear Russian retaliation, Putin is coming under growing pressure to enforce redlines against the West,” Beebe argued. “His critics are arguing that unless he draws a firm line soon, there will be no limits to what the United States might provide to Kyiv.”

With the risk of escalation continuing to grow, it’s useful to look back at how pressure on Putin has grown in response to Western decisions to cross his red lines.

HIMARS (June 2022)

The Biden administration spent the first months of the war arguing that any transfer of High Mobility Artillery Rocket Systems, better known as HIMARS, would represent an unacceptable provocation for Russia. But, as Ukraine turned the tide in April and May of last year, the U.S. decided it was time to give Kyiv the advanced weapon system.

Notably, the decision came with significant strings attached. Colin Kahl, who then served as undersecretary of defense for policy, said the U.S. had secured promises from Ukraine that the HIMARS would not be used to attack targets within Russia — a promise backed up by the fact that Washington was only sending shorter range rockets for use with the high-tech system.

“We don’t have an interest in the conflict in Ukraine widening to a broader conflict or evolving into World War III, so we’ve been mindful of that,” Kahl told reporters at the time. “But at the same time, Russia doesn’t get a veto over what we send to the Ukrainians.”

The move drew immediate blowback in Russia. One prominent Russian television host said providing the weapons would “clearly cross a red line,” adding that she sees the move as “an attempt to provoke a very harsh response from Russia.” Later in the summer, Duma member Mikhail Sheremet said U.S. policy “has long crossed all permitted red lines, thereby continuing to push the country into the abyss and chaos at full speed.”

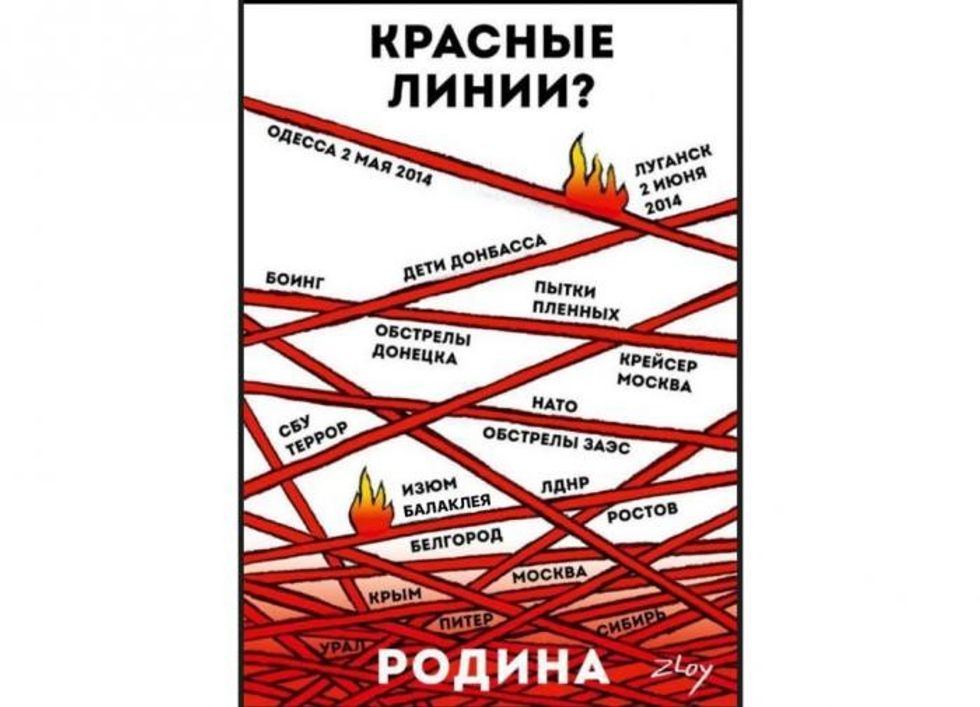

Russian hawks continued to put pressure on the country’s leadership as Western support grew. By September of last year, these critiques had grown so loud that Pravda, a loyal government outlet, published a meme skewering the Kremlin for allowing the West to cross so many red lines in recent years.

A political cartoon published in Pravda shows a tangle of Russian "red lines" that the West has crossed since 2014. The bottom of the image contains the names of several cities within Russia, suggesting that Western states are getting closer to directly attacking the Russian "motherland".

Despite this pressure, the Kremlin did little to back up its claimed red lines. In October, Alexei Polishchuk, a high-ranking Russian diplomat, seemed to move the goalposts when he said that “the supply of long-range or more powerful weapons to Kyiv” would be a red line for the Kremlin.

M1 Abrams tanks (January 2023)

Just a few months after Polishchuk’s comments, the U.S. agreed to send Ukraine its most powerful weapons system yet: the M1 Abrams tank. Officials had previously argued that the vehicles would create too many logistical and maintenance problems for Ukraine, and escalation concerns almost certainly factored into the administration’s hesitation. But once Germany decided to send some of its own Leopard II tanks, the decision became easier for the United States.

In his announcement of the move, Biden played down the risk of escalation. “It is not an offensive threat to Russia,” he said. “There is no offensive threat to Russia. If Russian troops return to Russia, where they belong, this war would be over today.”

Russian officials called Western decisions to give tanks to Ukraine “extremely dangerous” but also appeared to play down the importance of the move as a “rather disastrous plan” that would provide little help to Kyiv.

But Russian experts became more brazen in their criticism in the ensuing months. By March, former Russian leader Dmitry Medvedev had suggested that Moscow should consider using nuclear weapons in the conflict if Ukraine began to target what Russia considers to be its territory, including Crimea. In April, political scientist Sergei Markov said “angry patriots” wanted the Kremlin to respond more emphatically to what they view as direct American attacks on Russia.F-16s (May 2023)

Since the earliest days of the war, the Biden administration expressed concerns about the ramifications of sending fighter jets to Ukraine. At one point last year, the White House even blocked a Polish proposal to send Russian-made planes to Kyiv due to worries about escalating tensions with Moscow.

The Pentagon was reportedly at the heart of opposition to transferring F-16s, while Blinken played down concerns about escalation by noting that Russia has failed to back up any of its red lines so far. As recently as February of this year, Biden deflected on the question, arguing that Ukraine “doesn’t need F-16s now.”

In the end, Blinken and his allies won out. Biden announced in May that the U.S. would allow Denmark and the Netherlands to send some of their F-16s to Ukraine. Ukrainian pilots have started to undergo intensive training on how to operate the planes, which are expected to arrive in the next year.

Russia said F-16s would be a “colossal risk” due to the fact that the planes are capable of carrying nuclear weapons. (Ukraine, it should be noted, does not have access to nukes.) One prominent Russian blogger took a shot at Moscow’s unwillingness to enforce the red line against F-16s, writing that “if our officials do not take timely and decisive action, the situation will systematically continue to deteriorate.”

A retired Russian general took it a step further and suggested that Moscow should move tactical nuclear weapons to bases near Ukraine or even consider attacking airfields in NATO countries that might deliver F-16s.ATACMS (September 2023)

In July 2022, Jake Sullivan argued that sending long-range missiles to Ukraine would risk putting the U.S. and Russia on “the road towards a third world war.” That stance drew significant attention from Ukraine’s most zealous backers in the U.S., including Rep. Adam Smith (D-Wash.), who accused Biden last year of “buying into Putin’s rhetoric” on the issue.

Biden has so far held the line on Army Tactical Missile Systems, arguing in December that the potential for escalation to a NATO-Russia war was too great to countenance. But recent reports indicate that the administration is set to shift its policy yet again after months of pressure. By some accounts, an aid package including ATACMS could be announced as soon as this week.

If those reports are true, Russia will almost certainly see the move as a major provocation, as Biden himself argued last year.Attacks inside Russia and the path toward escalation

Much of this debate centers on one key question: Should the U.S. encourage Ukrainian attacks within Russia? Blinken’s recent comments suggest that the Biden administration has shifted its position on this question from a hard “no” to a tacit “yes”.

As Russian hawks continue to call for escalation, Putin is left with a dwindling set of options for signaling his displeasure with American policy on the war. Among other things, he could shoot down a Western plane flying near Russian airspace, or perhaps set up a covert attack against a NATO base, as he did with a Czech arms depot in 2014. As Beebe of the Quincy Institute has noted, Putin could also attack American satellites in order to hurt Western logistical support for Ukrainian operations.

But a more ominous threat looms on the horizon. If Ukraine starts to rack up more military successes with advanced Western weapons, some analysts worry that Putin could reach for the ultimate weapon.

“If the Russian military is not able to escalate or to prevent Ukraine from [retaking its territory], Putin will have no other way of escalating the war militarily than through a nuclear weapon,” retired Gen. Kevin Ryan told RS earlier this year.