The presidency of Israel is a largely ceremonial job, although most of the occupants of that position have been experienced politicians who have weighed in on policy problems of the day. That is true of the current Israeli president, Isaac Herzog, who has held several ministerial positions and has attempted to mediate differences over the current Israeli government’s plans to emasculate the Israeli judiciary. Herzog’s visit to Washington this week, which includes an address to Congress, thus will not carry as much baggage as would a visit by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

Netanyahu is the head of the current extreme right-wing Israeli government and is responsible for its most controversial policies in ways that Herzog is not. Netanyahu, moreover, has allied with the Republican Party and has interfered in domestic American politics more blatantly than other Israeli leaders. President Biden thus has had multiple good reasons to have resisted inviting Netanyahu for an official visit, although this week, just as Herzog was about to arrive in town, Biden gave in to the usual political pressure to display closeness to Israel and issued such an invitation.

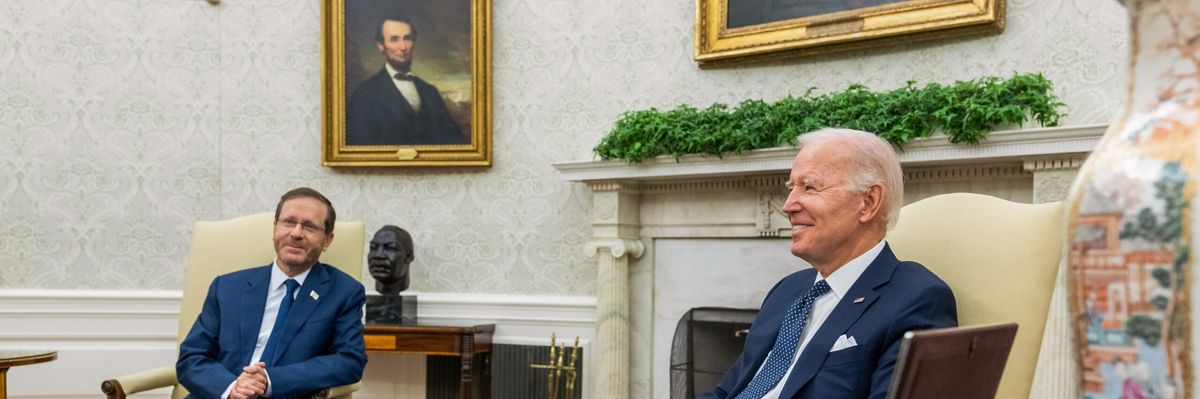

Herzog will present a friendlier and more moderate face to America, and there may be some elements of a good-cop-bad-cop routine in what will now be successive visits by him and Netanyahu. At events this week, Biden will be able to share warm vibrations about U.S.-Israeli friendship, as will most, though not all, congressional Democrats. But the vibrations will not obscure the significant differences between interests of the United States and Israel.

Herzog has said that his speech to Congress will emphasize “the essential need to fight against the hatred and terrorism that Iran is spreading while it pursues nuclear weapons.”

Regarding Iran, the first thing to note is that no government has done more to stoke tension and animosity involving Iran than that of Israel. Spreading of hatred, including explicit threats of military attack, has been more apparent in what comes from Israel and is directed against Iran than what flows in the opposite direction.

Netanyahu takes second place to no one in Iran-bashing, but the pattern just described is hardly unique to him. Take, for example, the speeches by world leaders at the United Nations General Assembly in 2021, when Naftali Bennett was still prime minister of Israel. After a speech by Iranian President Ebrahim Raisi that barely mentioned Israel — just two sentences expressing support for Palestinians living under occupation — Bennett devoted nearly a third of his slightly longer speech to attacking Iran and blaming it for nearly every ill in the Middle East.

The Israeli objectives in making castigation of Iran a centerpiece of its declaratory policy go well beyond nuclear activities and even other issues directly involving Iran. The Israeli promotion of isolation, punishment, and hatred of Iran — and opposition to any diplomatic agreement, on any subject, with Tehran — serves several Israeli objectives. It weakens a competitor for regional influence. It erects a political barrier against any U.S. rapprochement with Iran. It blames Iran for everything wrong in the region and deflects blame away from anything Israel has done. And it is the all-purpose deflector of attention away from subjects, such as the subjugation of Palestinians, that Israel does not want to talk about. These are not interests that the United States shares.

The obsession with opposing any agreements with Iran has worked sometimes against Israel’s own security interests. This was true of Israel’s opposition to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the multilateral agreement that closed all possible paths to an Iranian nuclear weapon. Senior Israeli security specialists — especially retired officials who were free to speak their minds — viewed Israel’s opposition to the JCPOA as a mistake.

The subsequent several years proved them correct, as many of them later reaffirmed. In contrast to the years in which the JCPOA was in force and Iran abided by its terms, the years since Donald Trump reneged on the agreement in 2018 — to applause from the Israeli government — have seen a vast expansion of Iran’s nuclear program, accompanied by Iranian regional policy that is at least as assertive as it was when the JCPOA was in effect and Iranian politics that are more hardline than before.

Today, the best hope for repairing some of the damage from the trashing of the JCPOA rests with a possible unwritten understanding that would at least put a lid on further escalation of tension, and the risk of war, between Iran and the United States. Such an understanding would be in the interests of the United States and regional peace and stability. It also would be in the interest of Israel’s security — but would not advance Israel’s blame-and-attention-deflecting interest in opposing all agreements with Iran. Herzog might, and Netanyahu probably will, express open opposition to even this sort of modest understanding with Tehran.

Herzog also will praise the expansion of Israel’s relations with certain Arab states to include exchange of embassies and ambassadors, an expansion that commonly goes by the grandiose name of “Abraham Accords.” Notwithstanding Biden’s politically motivated and misguided adoption of this Israeli cause as his own and desire to extend the expansion to Saudi Arabia, this is another subject on which U.S. and Israeli interests diverge. The expansion of relations does not constitute a “peace” agreement, given that none of the Arab states concerned had been fighting a war against Israel. And whatever benefit is to be gained from relations between Israel and those Arab states is to be had by the extensive cooperation, including on security matters, that already existed without an exchange of embassies.

The upgrading of relations with the Arab states serves two main Israeli objectives, neither one of which conforms with U.S. interests. One is to sharpen lines of conflict in the Persian Gulf region and to solidify confrontation with Iran. The other is to demonstrate that Israel can enjoy normal relations with regional neighbors without having to end the occupation of the West Bank and resolve the conflict with the Palestinians. Far from being a peace agreement, the expansion of relations with the Arabs is about not making peace with the Palestinians.

While Herzog can be expected to devote much of his speech at the Capitol and other remarks to how awful Iran is and how wonderful the “Abraham Accords” are, he probably will say little about the judiciary-emasculating measures of Netanyahu’s government that have rocked Israel with massive street protests. He is likely to say even less about the unending occupation and conflict with the Palestinians and associated upsurge in violence, other than with the usual Israeli attribution of blame to “terrorists,” especially Iranian-supported ones, for the violence.

The subjects that the Israeli president wants to talk about and the ones he does not want to talk about are intimately related. Israel’s continual pushing of the former onto the international agenda is intended to keep the latter off that agenda.

The United States has an interest in lowering, not raising or sustaining, tensions in the Middle East. It has no interest in perpetuating one conflict and then stoking another to deflect attention from the first one. Nor does it have an interest in being dragged into someone else’s regional rivalries. It has good reason to applaud measures, such as the restoration of relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, that have far more than symbolic significance and really do involve a reduction of regional tensions.

Herzog may be a friendlier face than the prime minister who will be coming to town later, but these realities about interests and objectives should be kept in mind as one listens to what he says.