In February 2019, then-freshman congresswoman Ilhan Omar committed a rare offense in U.S. politics: she called out a sitting official, to his face, for his complicity in horrific human rights abuses.

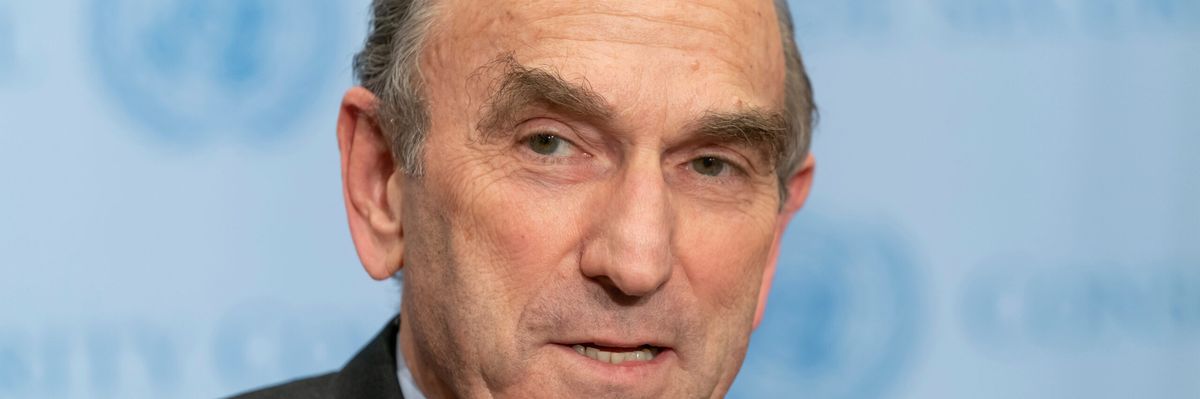

The official in question was Elliott Abrams, who had just been appointed the Trump administration’s “special envoy” for Venezuela. Omar highlighted Abrams’ 1991 guilty plea for lying to Congress about the Iran-Contra affair, saying that this called into question why members of the body should trust what he has to say. She went on to excoriate Abrams for his role in downplaying the horrific massacre of hundreds of civilians by U.S.-armed and trained troops in El Salvador.

The reaction to Omar’s breach of decorum was swift and bipartisan. A number of neoconservative intellectuals leapt to defend Abrams as a champion of democracy and human rights, joined by a handful of nominally liberal foreign policy professionals such as Kelly Magsamen, then vice president for National Security and International Policy at the Center for American Progress, and now chief of staff to Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin.

“I worked for Elliott Abrams as a civil servant,” Magsamen tweeted. “He is a fierce advocate for human rights and democracy. Yes, he made serious professional mistakes and was held accountable. I’m a liberal but I’m also fair. We all have a lot of work to do together in Venezuela. We share goals.”

This strange episode gained renewed relevance on Monday when, in a possible attempt to bury the news on the eve of the Fourth of July, the Biden administration announced its intent to nominate Abrams to the bipartisan “United States Advisory Commission on Public Diplomacy.”

The commission is charged with assessing U.S. efforts to “understand, inform, and influence foreign publics” and issuing reports to Congress and the executive on these topics. It is statutorily bipartisan; no more than four of its seven members can come from any one political party.

Abrams' appointment may be largely symbolic and grant him little power or influence over policy. But his selection, rather than any of the many available Republican former officials with less blood-stained careers, speaks volumes.

Abrams may not be as infamous as Henry Kissinger, but his record of “public service” is similarly ignominious, littered with the policy failures and complicity in crimes against humanity that have unfortunately characterized U.S. foreign policy in the Cold War era and beyond.

In 1981, a day before Abrams assumed the post of Assistant Secretary of State for Human Rights and Humanitarian Affairs, the Atlacatl Battalion, a U.S.-trained unit of the Salvadoran military, massacred nearly 1,000 civilians, committing mass rapes against women and children in the process. Abrams insisted to Congress that rumors of the massacre were essentially propaganda by leftist guerillas, and continued to do so despite investigations by U.S. embassy officials, the New York Times, and the Washington Post confirming the massacre and placing blame squarely at the feet of the Salvadoran military.

Throughout the Reagan administration's brutal counterinsurgency campaigns in Central America, Abrams continually testified that U.S.-backed forces were making serious improvements in their human rights practices so that they could continue receiving arms and training. In fact these forces in Guatemala and El Salvador were waging murderous war against their countries’ peasantry and indigenous populations. A U.N.-backed truth commission eventually found that 85 percent of the violence was carried out by the military and its associated death squads.

Abrams reserved particular praise for Guatemalan dictator Efrain Rios Montt, lauding the dictator for “considerable progress” on human rights and attitudes toward the indigenous population. Rios Montt was later convicted of genocide against Guatemala’s Ixil Maya.

Abrams is best known for his central role in the Iran-Contra Affair, working to secure funding for the brutal counterrevolutionaries and to direct their operations. The Contras, a group consisting mostly of former officials and soldiers from the deposed dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza, failed in their task of overthrowing the Sandinista government in Nicaragua. But the militants, who were almost completely reliant on U.S. support, became notorious for their brutal killings of civilians.

It was for this affair that Abrams would earn his criminal conviction — not for abetting and concealing mass atrocities, but for misrepresenting U.S. support for the Contras to Congress. In 1991, Abrams pleaded guilty for lying to Congress about the extensive U.S. role in supplying and funding the Contras, for which he received two years of probation and 100 hours of community service — a punishment he never actually served after an 11th-hour pardon from George H.W. Bush.

The contention that Abrams merely “made mistakes” and was held accountable — more popular with his liberal defenders — is belied by this pardon and by Abrams’ book Undue Process, his angry and self-pitying account of his prosecution in which he labels Iran-Contra investigators “miserable, filthy bastards” and “bloodsuckers” (and which this author has had the misfortune of reading in full).

Abrams’ record of abuse and failure continued into the 21st century. He served in the George W. Bush administration and was alleged to have approved the failed coup plot against Hugo Chavez in 2002. Later, he was named as a central figure in the administration’s backing of a failed 2007 Fatah coup against Hamas after the latter party won Palestinian elections — ultimately leading to Hamas’s uncontested control of the Gaza strip.

In his aforementioned time as Trump’s “special envoy” for Venezuela, U.S. policy fared no better, with attempts to overthrow the government of Nicolas Maduro ending only in Juan Guaido’s spectacularly unsuccessful 2019 putsch attempt and an even more quixotic effort by a group of U.S. mercenaries and former Venezuelan soldiers to kidnap Maduro. The Trump administration denied any involvement in the latter affair, which historian Greg Grandin has described as a “burlesque Iran-Contra.”

In response to a query from Mother Jones, a White House spokesperson implied that Abrams’ nomination to this latest appointment was put forward by Republican leadership and merely accepted by the administration. But given the White House’s vague explanation of the willingness of members of the administration to publicly embrace Abrams and others like them, it would be granting Team Biden far too much benefit of the doubt to simply believe that Republicans forced their hand.

Biden entered office pledging that “human rights will be the center of our foreign policy.” Since then he has comprehensively broken this promise, as recounted last month by former Bernie Sanders advisor Matt Duss (who also sharply criticized Abrams' nomination). In embracing great power competition — particularly confrontation with China — at all costs, the Biden administration has made some degree of human rights hypocrisy inevitable. The United States embraces repressive and murderous (but useful) governments while in the same breath condemning the human rights abuses of its adversaries and calling on the world to rally behind liberal principles.

This contradiction is readily apparent in the administration’s campaign against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In March, Antony Blinken gave a speech highlighting Russia’s massacres of civilians in Bucha, appealing to the world to rally for justice and against Russia’s war. Just two months later, Blinken joined other foreign policy luminaries for the 100th birthday party of Henry Kissinger, who is directly responsible for the massacre of countless civilians in Cambodia and beyond.

That Biden officials do not see how hypocritical — and counterproductive — it is to embrace figures like Abrams and Kissinger while trying to rally the globe against their adversaries human rights abuses is almost unfathomable. But the exceptionalist convictions held by most U.S. foreign policy elites — that American power is synonymous with liberal order, and that U.S. global primacy is, in the words of analyst Van Jackson, a “global public good” — are powerful and enduring.

The problem for America’s foreign policy establishment is that it is increasingly impossible for anyone outside of Western elites to believe this too. Over the coming years the United States will be faced with a choice to either adopt a more humble foreign policy that accepts the same restraints it demands of others, or to drop the pretenses altogether.