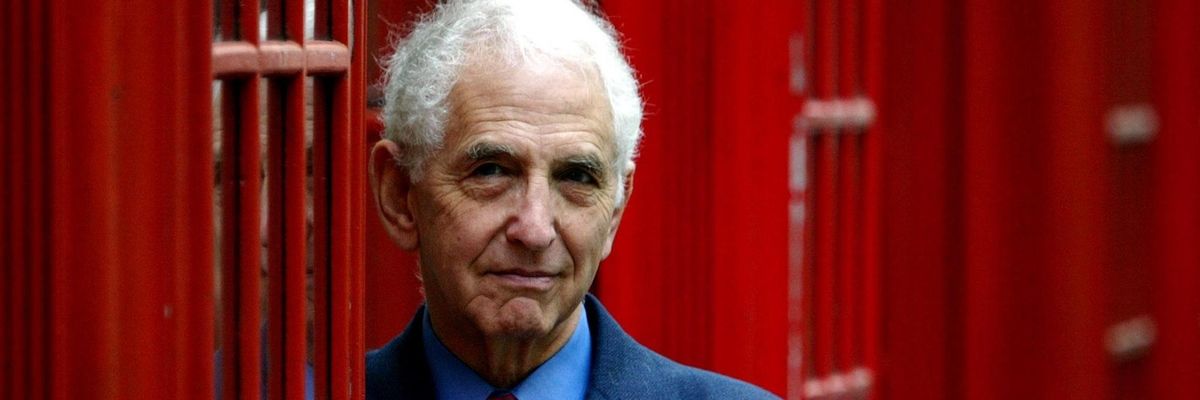

To my sons and my grandchildren, Dan Ellsberg was funny, inquiring, an excellent magician — not a whistleblower. He was always eager to show off his newest trick and learn about the latest technology.

Dan was constantly and deeply engaged in the issues of the day. But he also remained curious about the relation between his release of the Pentagon Papers, as the history of American engagement in Vietnam came to be called years after I directed its production from the Office of the Secretary of Defense, and the end of the war in Vietnam. We discussed this regularly, including in our last conversation just weeks ago.

Dan had no illusions that the accepted story was correct.

He gave the papers to the press, the press published them, citizens read them and took action to end the war. None of this was accurate. As his deservedly prominent obituaries make clear, the story of how the papers got from Dan to the New York Times was complicated. The Times never published the full text which was his original demand. Few people read the full stories, and fewer still had their minds changed. The war went on for many more years and the attacks on North Vietnam escalated.

Dan recognized all of this. He claimed credit deservedly for doing what he could to end the war, including risking a long jail sentence for the crime that Donald Trump is now charged with. He did think his release of the papers played an important role in finally bringing the war to an end but in a much more convoluted way.

It was a surprise to Dan that Nixon was so rattled by the publication of a history which ended a full year before he came into office and which showed Democratic presidents from Truman to Johnson lying to the American people about the nature of the conflict and the prospects for the United States winning the war.

Nixon claimed to have a new plan, and the public tended to believe him. Why then were Kissinger and Nixon concerned? The answer, Dan believed, and I agree, was that they feared that Dan had documents from the Nixon administration and would make those public. Dan in fact had such papers, having worked as a consultant to Kissinger and me on the NSC staff in the early days of the administration. Nixon created the plumbers to stop him, and the plumbers led to Watergate. And the war finally ended when Congress, emboldened by the scandal, cut off the funding for the war. This was the actual way that Dan believed he helped bring about an end to the Vietnam War. He was proud of his role and endlessly curious about the details.

Dan was, no doubt, America’s most prominent whistleblower. He worked tirelessly to encourage others to speak out when the government was keeping the truth from the American people, particularly on matters of war and peace, and to support those who did. He never wavered from his belief that we were entitled to the full truth and that whistleblowers should be honored and certainly not prosecuted.

He had intended to follow up on the release of the Pentagon Papers by publishing a stack of documents on American nuclear policy which was his primary professional interest for many years. He had asked his brother to store the documents and, through a bizarre set of accidents, they disappeared. Dan deeply regretted that he was not able to make public documents which demonstrated how reckless American nuclear policy is and how close we have come on several occasions to nuclear war.

Perhaps his last act of personal whistleblowing was to make public a still Top Secret study of the 1958 Taiwan Straits crisis which I had written for RAND in the early 1960s. The study showed that the Joint Chiefs of Staff were pressing for almost immediate use of nuclear weapons if ordered to defend the tiny island of Quemoy close to the Chinese mainland and that President Eisenhower seemed ready to authorize using nuclear weapons to attack China. It was one of the few nuclear documents he had, and he decided to put it out while he still could. To Dan’s regret the release did not stimulate a debate on nuclear policy. To his relief, he was not indicted. Still, it was the right thing to do.

He was at peace at the end knowing he had done what he could and taken significant personal risks to do what he thought was right.