Since the start of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, U.S. policy toward the conflict has inter-mingled uneasily with the U.S. government’s growing convergence with the social media platforms that make up today’s digital public square.

Tech companies have selectively relaxed their bans on violent and hate speech to align with Ukraine’s war effort, shuttered the accounts of media outlets critical of the war and U.S. policy to it, and seen a vast army of bots push content supporting Ukraine and its NATO partners. And now, Facebook is actively censoring and discouraging the sharing of Seymour Hersh’s reporting on the alleged U.S. role in the attack on the Nord Stream pipelines.

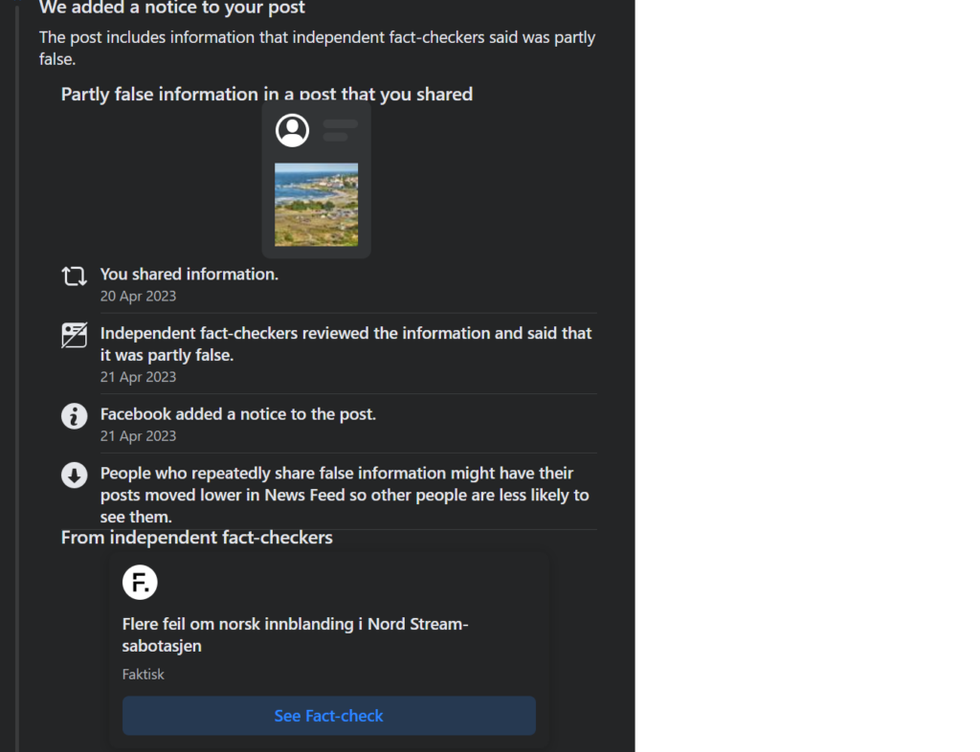

As of Thursday, if you try to share on Facebook the February 8 Substack post in which Hersh first laid out the anonymously sourced charge, you’ll first be met with a prompt informing you about “additional reporting” on the subject in the form of Norwegian fact-checking website Faktisk, and warning you that “pages and websites that repeatedly publish or share false news will see their overall distribution reduced and be restricted in other ways.”

If you decide to “share anyway,” Hersh’s piece is posted but blurred out, and labeled “false information” by the social media platform. (It’s since been unblurred and labeled “partly false information”). The phenomenon was first pointed out by Michael Shellenberger, and has since been replicated by others, including myself.

Besides labeling the post as false, Facebook also sent me a notification roughly 10 hours later informing me about the notice they’d added and that I had shared something that “includes information that independent fact-checkers said was partly false.” Facebook cautions that “people who repeatedly share false information might have their posts moved lower in News Feed,” suggesting that if I go on to share any other reporting that’s been challenged by fact-checkers, I’ll be punished by having my account’s reach throttled.

Yet the fact-check in question from Faktisk — Norwegian for “Actually” — leans heavily on open source intelligence whose reliability has itself been recently challenged. Hersh has previously fended off criticism that his reporting doesn’t match up with public data about ship movements by arguing this information can be manipulated. Indeed, in a piece putting forward its own, alternate theory to Hersh’s, the New York Times itself noted that the pipelines weren’t closely monitored by commercial or government sensors, and that there were roughly 45 “ghost ships” whose location transponders weren’t on.

Faktisk, incidentally, is a partnership between Norway's two largest online news outlets, VG and Dagbladet, and its public broadcaster NRK, which is much like the New York Times, Washington Post and PBS starting a joint fact-checking project.* Given that Norway is implicated in a major way in the alleged attack in Hersh's report, this raises the uncomfortable specter of a possible conflict of interest — especially as Faktisk's editor-in-chief is a former NATO officer himself.

Quite apart from this, however, like their US counterparts, mainstream Norwegian press outlets —including VG and Dagbladet specifically — have long been criticized for their war-friendliness and for reflecting elite opinion more generally, including that of the US government.

Of course, Hersh’s story is yet to be corroborated, and it’s entirely possible that, even if it’s ever proven true in the broad strokes, it ends up wrong on specific details. But while the story’s veracity is far from certain, it’s hard to see how it can be unequivocally declared “false” — to the point of threatening to throttle the accounts of those sharing it — given the admitted flaws in open source intelligence, and given the circumstantial evidence backing the central claim of Hersh’s high-level anonymous source: that the attack was a U.S. operation. Western officials have now told the press there’s little enthusiasm for finding out the truth, fearing it could be a friendly government.

It’s also vastly different to the treatment Facebook metes out to theories that are at least equally dubious, but have been disseminated through legacy news outlets instead of Substack. The New York Times’ alternate theory of a “pro-Ukrainian group” unconnected to any government being behind the attack can be posted on Facebook without issue, as can the Die Zeit report alleging that this pro-Ukrainian group was made up of six people who used a rented yacht.

Yet both stories have been challenged since publication. Swedish investigators have reaffirmed that they believe a state actor is the most likely culprit, and law enforcement officials told the Washington Post they’re skeptical about the veracity of the German report, doubting both the claims that a yacht was used or that a six-person crew could have pulled off the operation, including laying the explosives by hand. There were doubts about the Times’ theory to begin with, given that the U.S. officials promulgating it loaded it up with qualifiers, and stressed there were “no firm conclusions” while refusing to discuss the evidence they based it on.

Mainstream stories alleging that Russia destroyed its own pipeline also don’t meet any pushback from the platform. That includes this Bloomberg piece about a German official blaming Moscow, this Insider piece that cites “Russia experts” who argue the attack was a “‘warning shot’ from Russian president Vladimir Putin to the West,” and this Telegraph piece that purports to explain “why Putin would want to blow up Nord Stream 2, and the advantages it gives him,” asserting that it’s “ripped straight from [his] playbook of panic, escalation and misdirection.”

This is despite the fact that such accusations clash with the now-official narrative of a pro-Ukrainian, non-state group, and that even Western officials now openly doubt Russia’s culpability for attacking its own pipeline, which could cost half a billion dollars to repair by one estimate.

This attempt to hobble the spread of Hersh’s story on Facebook is a small taste of the alarming implications of when tech censorship combines with government pressure, and suggests how easily independent reporting can be throttled while allowing official misinformation to proliferate. By stifling open, public debate about an issue of such grave and urgent importance, the result is not just threatening to a free press, but to U.S. democracy more broadly.

Editor's Note: This story has been updated with information about Faktisk's (Norway) public funding.