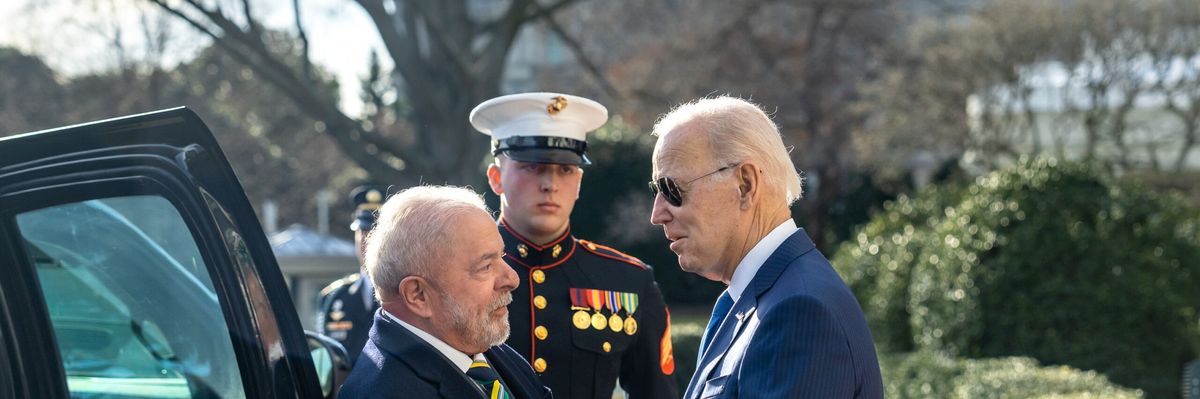

U.S.-Brazilian relations have not improved much since President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva took office in January. Despite hopes for a “new era” in relations connected with Lula’s visit to the U.S. in February, the first few months have not been very productive.

One major reason why relations have not improved more is that Washington has had unrealistic expectations that the Brazilian government would support a U.S.-led agenda. To the extent that Lula has disappointed the U.S. since returning to power, it is largely because many people in our government mistakenly assumed that Lula ought to fall in line behind Biden and became frustrated when he did not. Brazil under Lula charted an independent course when he was president in the 2000s, and it is certain to do so again now.

This is a problem for the U.S. only if Washington insists that every country must toe its line and do its bidding.

Much as Biden did when he took office, Lula took the opportunity during a state in China this week to boast that “Brazil is back!” He stressed that his foreign policy will resume the international engagement that his predecessor neglected, and his openness to working with both the U.S. and China is part of that. Many in Washington will be tempted to see a productive Brazilian-Chinese relationship as a threat to be countered, but that would be a mistake.

Washington isn’t going to have much success in cultivating good relations with its neighbors like Brazil if it buys into the emerging anti-Lula narrative that is taking hold in Washington today. A recent Washington Post report presented the problem in the U.S.-Brazilian relationship as one entirely of Lula’s making.

“The West hoped Lula would be a partner: he’s got his own plans,” the headline read. In this case, the “partnership” in question seems to be one where Brazil ought to agree with everything the U.S. wants and should never pursue its own interests. Most of the article is a litany of all the ways that Lula’s foreign policy does not conform to American preferences, and the report overstates the significance of these differences to make them seem more alarming.

The report presents Lula’s emphasis on “pragmatism and dialogue” in foreign policy as being at odds with “promoting democratic norms in the Western Hemisphere and beyond,” but there is no contradiction between the two. The real problem, as the article soon makes clear, is that Lula “shows little concern over whether it antagonizes Washington or the West.”

Since the U.S. tends to be antagonized over remarkably minor things when other states pursue their own independent course, maybe the trouble here is not Lula’s lack of concern but rather Washington’s hypersensitivity.

Take the matter of the two Iranian ships. The article mentions that the Brazilian government “allowed Iranian warships to dock in Rio de Janeiro” in February, but it does not acknowledge that Lula delayed the docking so that it did not embarrass the Biden administration during Lula’s visit. It is never explained why allowing the ships to dock was supposed to be such a terrible thing or why Lula shouldn’t have allowed it.

The Iranian ships are never mentioned again in the rest of the article, and that’s probably because their port call didn’t matter and threatened no one. There is no reason why this minor event should cause even a ripple in U.S.-Brazilian relations, but because of overreaching U.S. sanctions and a bankrupt Iran policy it was the cause of controversy.

The Biden administration complained that the ships had “no business” docking anywhere. Some members of Congress and the media went into a panic over the brief presence of the ships. Sen. Ted Cruz threatened Brazilian companies with sanctions because of this unimportant event, and The Wall Street Journal charged that “President Biden’s domestic political agenda trumped security in the Americas.”

The article presents the decision to allow the ships to dock as an example of how Brazil risks alienating the U.S., but on closer inspection it is a good example of how the U.S. ends up picking fights with its neighbors over things that don’t matter in a way that is bound to irritate our would-be partners.

Another item mentioned in the report is Lula’s willingness to resume contacts with the Maduro government in neighboring Venezuela, but this outreach should be seen as a positive development. The renewal of contacts between Brazil and Venezuela is part of a broader trend in the region. More and more people in the Americas have woken up to the costly failure of the U.S.-led push to remove Maduro from power, and some, including Lula, were opposed to the attempted regime change from the start.

The U.S. needs to face the reality that its Venezuela policy has been a disaster for the people of Venezuela and for Venezuela’s neighbors and it should change course as quickly as it can. The Brazilian government could prove to be a valuable partner in devising a new, less destructive approach to Venezuela’s crisis.

The U.S. has often struggled in managing its relations with non-aligned states, especially when they have democratic governments. The last time Lula was president, the Obama administration swatted down its efforts to find a compromise on the nuclear issue with Iran. The real problem that Washington had with the deal that Brazil and Turkey brokered back then was not so much with the terms of the agreement but with the temerity of other states to negotiate a diplomatic solution that wasn’t already approved by the U.S.

It should be taken for granted that other governments’ leaders have their own agendas that won’t always line up with what the U.S. and its allies want. This is not a failing on the part of the other governments, and the U.S. should not reproach them for securing their own interests. No two countries are going to have interests that converge all the time, and large democratic countries are bound to have different foreign policy priorities because of their respective histories and the preferences of their voters.

The U.S. and Brazil can be partners, but that requires mutual respect and an understanding that partners work together as equals. This can’t just be something that our officials say in their press statements, but it must also be something that our government practices in its dealings with the other state. The U.S. should focus its attention on the interests that it has in common with Brazil on trade and climate change rather than dwelling on the issues where we know there are disagreements.

The U.S. can have an improved and constructive relationship with Brazil in the coming years, but it needs to be willing and able to deliver on the issues that matter to their government. Whether Washington is up to the challenge remains an open question.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org