During a visit to Moscow this week, Chinese President Xi Jinping renewed his call for a diplomatic end to the war in Ukraine.

“The majority of countries support easing tensions, advocate peace negotiations and oppose pouring oil on the fire,” Xi told Russian President Vladimir Putin, according to a Chinese readout of their meeting. “Historically, conflicts must finally be settled through dialogue and negotiations.”

The comments drew a sharp rebuke from Washington, which framed Xi’s avowed support for peace as a “stalling tactic” meant to help the Kremlin consolidate its gains in Ukraine. “The world should not be fooled by any tactical move by Russia, supported by China or any other country, to freeze the war on its own terms,” said Secretary of State Antony Blinken.

Blinken also condemned the timing of the visit, which came just days after the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for Putin’s arrest on charges of war crimes in Ukraine. “Instead of even condemning [Putin’s alleged crimes] it would rather provide diplomatic cover for Russia to continue to commit those grave crimes,” Blinken said.

At some level, this response is understandable. China’s close ties with Russia — and Xi’s insistence on referring to Putin as a “dear friend” — leave a clear impression that Beijing’s calls for peace are simply a roundabout way to support an ally in danger.

But there are also good reasons to believe that, as Beijing becomes more involved in the conflict, Washington’s confrontational approach could prove unwise.

As Ryan Hass of the Brookings Institution noted on Twitter, the Biden administration “could draw more support and have greater effect by making [the] affirmative case for what [a] constructive PRC role would look like” rather than “warning others not to be duped” by China. In other words, the U.S. should keep in mind that much of the world wants this war to end as soon as possible, and Washington is unlikely to change their minds about peace by attacking a potential mediator.

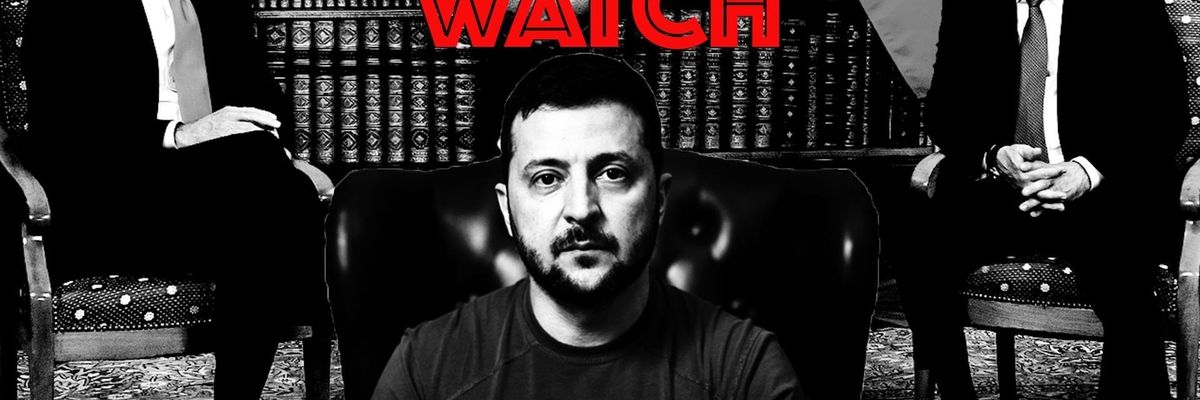

Even Ukraine, which rarely pulls punches when attacking Russia’s allies, has been careful not to dismiss China’s emerging role. “I think some of the Chinese proposals respect international law, and I think we can work on it with China,” said Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in a recent press conference. Zelensky has also said that he would like to speak directly with Xi. (To the Biden administration’s credit, top advisor Jake Sullivan praised the idea of a call between the two leaders.)

Zelensky’s cautious approach is likely rooted in Ukraine’s long-term interests. As Veronika Melkozerova noted in Politico, Beijing is a key trading partner for Kyiv and one of the few countries that could actually exert influence over Moscow in negotiations. “China’s deep pockets are also likely to play a role in helping Ukraine rebuild from the devastation of war,” Melkozerova wrote.

And there’s reason to believe that Washington’s core criticism of Beijing is based on a misreading of its stated position. As Gilbert Achcar of the University of London wrote in the Nation, “China’s plan does not call for an immediate and unconditional cease-fire, which would risk perpetuating Russia’s present occupation of a significant portion of Ukraine’s territory.”

Instead, Achcar notes, Beijing asks all parties to “support Russia and Ukraine in…resuming direct dialogue as quickly as possible, so as to gradually deescalate the situation and ultimately reach a comprehensive ceasefire.”

This apparent misinterpretation highlights the warped thinking that has seeped into U.S. discourse about China as a new cold war emerges between the two superpowers. As Trita Parsi of the Quincy Institute noted in the New York Times, Washington would be wise to not let competition with Beijing get in the way of efforts to bring about a more peaceful world.

“The greatest threat to our own security and reputation is if we stand in the way of a world where others have a stake in peace, if we become a nation that doesn’t just put diplomacy last but also dismisses those who seek to put diplomacy first,” Parsi wrote.

In other diplomatic news related to the war in Ukraine:

— Russia and Ukraine agreed Saturday to extend a UN-sponsored deal that allows ships to carry Ukrainian grain via the Black Sea, according to Reuters. Putin signaled that he would block future extensions of the agreement unless the West dropped certain sanctions related to Russian food and fertilizer exports. For their part, Western countries contend that their sanctions have sufficient exemptions to allow for Russian food exports.

— On Thursday, Putin advisor Dmitry Medvedev lashed out at the ICC’s decision to issue an arrest warrant for his boss and threatened to attack any country that attempts to arrest him, according to the Reuters. A top Zelensky aide said Wednesday that the warrant forecloses any possibility of negotiations “with the current Russian elite.”

— Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida visited Ukraine and met with Zelensky during a surprise trip on Tuesday, according to the New York Times. Kishida also made a stop in Poland, where he pledged financial aid to help Warsaw maintain its support for Kyiv.

— In an interview with Mark Hannah of the Eurasia Group Foundation, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Mark Milley reiterated his argument that the war in Ukraine is unlikely to be resolved on the battlefield. “At some point people will figure out that the cost of continuing to execute this war through military means is extraordinarily challenging,” Milley said. “Somehow someone's going to figure out how to get to a negotiating table, and that's where this thing will get settled out eventually.”

U.S. State Department news:

In a Tuesday press conference, State Department spokesperson Vedant Patel argued that “if China wants to play a constructive role in this conflict, then it should press Russia to remove its forces from Ukraine’s sovereign territory.”