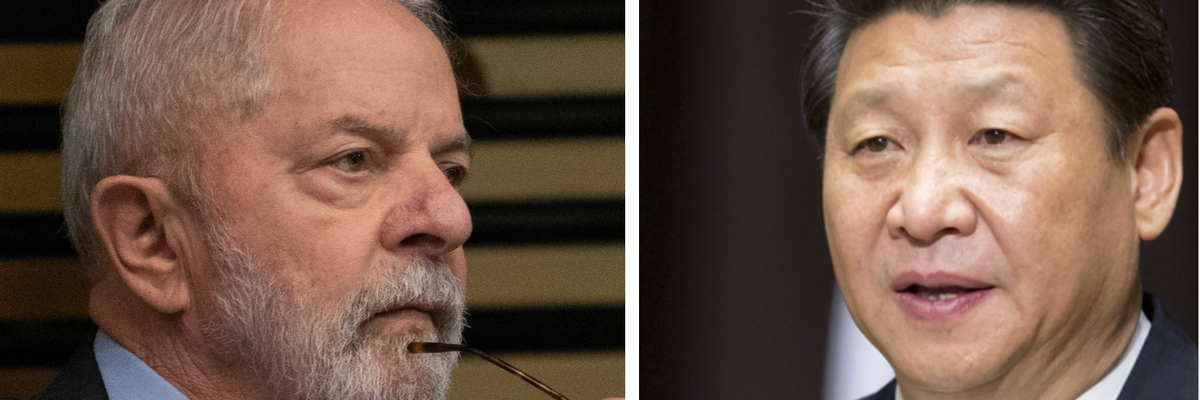

UPDATE: Brazil’s president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, 77, indefinitely postponed his trip to China during a bout of pneumonia, the presidential palace said Saturday. Officials have reportedly reached out to their Chinese counterparts with an intent to reschedule.

On March 23, Minerva, the Brazilian meatpacking behemoth named for the Roman goddess of strategic warfare, announced that the Chinese government would once again be importing beef from Latin America’s largest nation.

China had placed a month-long embargo on Brazilian meat after a case of mad cow disease was reported in the northern state of Pará. Now, Brazilian meat producers can reengage with the vast Chinese market, a voracious consumer of animal protein. But beef is not the only thing leaving Brazil for China in the coming days.

On Sunday, President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva will head to China for a visit set to last an entire week, a sharp contrast to the roughly forty-eight hours Lula spent in Washington during his visit last month and a reflection of the enduring trust deficit between Brasilia and Washington despite nominally warm relations right now.

In a way, the trade dimension is the least interesting aspect of Lula’s trip. Sure, the president will be accompanied by a large delegation of commercial representatives. “With 69 of the nearly 250 executives traveling,” Lisandra Paraguassu and Ana Mano reported on Wednesday, “meatpackers dominate a roster including wood pulp producers, a soy crushers group and executives from the mining, construction and financial services industry, according to a preliminary government list of the business delegations seen by Reuters.”

Trade is almost always desirable, and more trade is even better, particularly as Brazil’s economy remains stuck on neutral. But the geopolitical significance of Lula’s visit at this moment is particularly intriguing.

Earlier this week, Chinese president Xi Jinping met with Vladimir Putin in Russia to discuss a host of issues, including international cooperation, coordination to promote global development, and, of course, the Russian war against Ukraine. If Putin expected a torrent of military aid from China, however, he was disappointed. Instead, the joint statement between Xi and Putin emphasized the need for peace talks right away and the overriding aim of avoiding nuclear war.

Earlier this month, China released a twelve-point peace plan which Putin said could potentially be used to end the conflict that he started. That document, per Alexander Gabuev, senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “repeats Beijing’s support for the UN Charter and the territorial integrity of states, but at the same time condemns unilateral sanctions, and criticizes the expansion of U.S.-led military alliances.”

In its vague admonition of both Putin and the western alliance shoring up Ukraine as well as its overriding desire to see the war brought to a close, the Chinese position is remarkably aligned with Brazil’s. Indeed, in an interview with a leftwing Brazilian news site, Lula praised China’s framework for peace and criticized the U.S. reluctance to push for an immediate negotiated settlement. Lula’s comments were reportedly much discussed in the Chinese press.

Of course, since taking office for an unprecedented third term in January, the Brazilian president has called for the creation of a small group of countries totally uninvolved in the Ukrainian conflict — including, for example, China, India, Brazil, among others — to mediate a peaceful resolution. He brought this up in his February visit with President Joe Biden only to see it unceremoniously shot down.

This was how National Security Council Coordinator for Strategic Communications John Kirby answered a question about Lula’s proposal: “It’s really up to President Zelenskyy to determine if and when negotiations are appropriate and certainly under what circumstances. As President Biden has said countless times, ‘Nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine.’”

Lula’s visit to China will be taking place in a much different context. The Brazilian president will be meeting with a Chinese head of state who just met personally with Putin to impress upon him the need for a negotiated settlement. Lula will almost certainly restate his support for that outcome.

It is important to note that along with China and Russia, Brazil is a member of the BRICS, the loose confederation of promising emerging economies that also includes India and South Africa that rose to global prominence during Lula’s last stint in office. These countries maintain ongoing economic ties (in fact, former Brazilian president Dilma Rousseff will be the next head of the BRICS bank, at Lula’s appointment) and a kind of special relationship as an aspirational counterpoint to U.S. hegemony in international affairs.

The obvious danger for Brazil in this delicate moment is that some in Washington might interpret Lula’s long stay in China as a sign that he is favoring Beijing in the new cold war that so many in Washington seem so eager to wage. Lula’s agenda includes, for example, a visit to the headquarters of Huawei, the Chinese multinational conglomerate that has taken the lead in expanding 5G cellular coverage across much of the developing world, which the U.S. says raises serious digital security concerns.

There has also been some speculation that Brazil could sign onto China’s Belt and Road Initiative, the massive global infrastructure program funded by the Chinese government. Unlike several Latin American nations that have welcomed investments from Beijing, which officials in Washington say comes at the cost of long-term sovereignty, Brazil has long resisted joining the program. That could change next week.

The United States is openly concerned about further Chinese incursions in the Western Hemisphere, meaning that deepening ties between Brasilia and Beijing could possibly produce some friction with Washington. Lula has made clear, however, that his foreign policy is formulated in accordance with Brazilian interests rather than ideological considerations.

Lula’s week-long trip to China should not be seen as a kind of ideological approximation with Xi Jinping. Lula is nothing if not a democrat, as even a cursory glance at his personal history reveals. He may harbor a lingering distrust of the U.S. government for what he sees as undue influence over Brazilian affairs in the recent past — NSA spying on former president Dilma (confirmed) and purported U.S. Justice Department involvement in his 2018 arrest (alleged), to list only two recent episode — but that does not mean he sees China as the good guy in the complicated game of international intrigue.

Brazilian and Chinese interests do, however, align at present in some important areas, the most important being an investment in a multipolar world order. Brazil has long craved greater influence in international affairs. It has wanted a permanent seat on the UN security council and inclusion in the OECD for years. Both goals remain out of reach.

Lula’s visit is likely to signal deepening ties with China after that relationship suffered under former president Jair Bolsonaro, a far-right extremist who treated the threat of Communism as if he had won the 1968 presidential election rather than the 2018.

It might be too much to ask, but the Biden administration should welcome Brazil’s eagerness to engage even more with China. Lula has insisted time and again that he is a reliable democratic actor in a world besieged by authoritarian challenges. Bad actors might respond to his prodding in ways they would not if it came from Washington. Crucially, international observers must bear in mind that Lula is not a follower. He will seek to push China on policy, as he reportedly already has on environmental matters ahead of his trip this weekend.

Indeed, in looking ahead to Lula’s trip, one of the slogans of his 2006 presidential campaigns comes to mind: “let the man work.”