A push by Arab allies of the United States to bring Syria in from the cold highlights the limits of a Chinese-mediated rapprochement between the Middle East’s archrivals, Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Designed to drive a wedge between Syria and Iran, the push for detente is spearheaded by the United Arab Emirates, and supported by Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan.

It demonstrates that the Saudi-Iranian rapprochement has done nothing to reduce geopolitical jockeying and rebuild trust.

At best, the Chinese-mediated agreement establishes guardrails to prevent regional rivalries from spinning out of control, a principle of Chinese policy towards the Middle East.

The Saudi-Iran agreement also is an exercise in regime survival.

It potentially allows the two countries to pursue their respective economic goals unfettered by regional tensions.

For Saudi Arabia, that means diversification and restructuring of the kingdom’s economy, while Iran seeks to offset the impact of harsh U.S. sanctions.

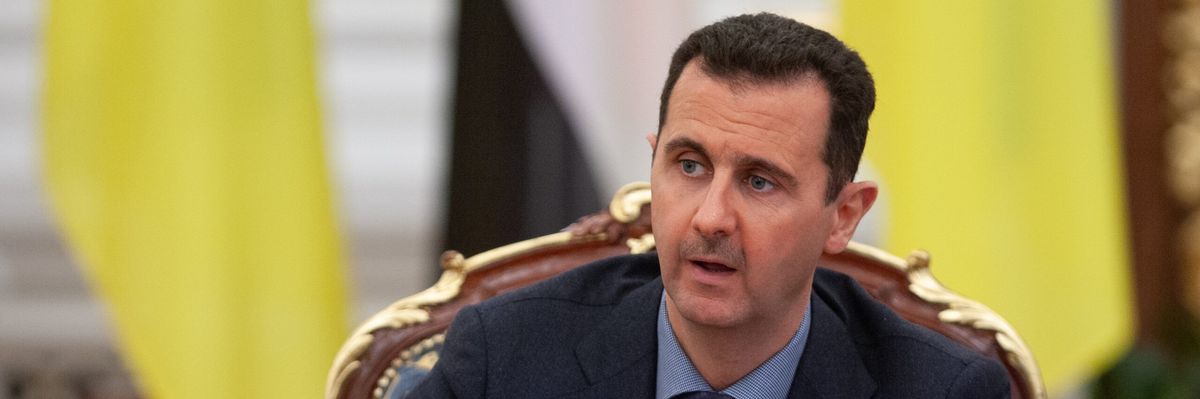

The goal of countering Iran in Syria is upfront in the Arab proposal for returning Syrian President Bashar al-Assad to the Arab and international fold.

If accepted by Syria, the United States, and Europe, it would initiate a political process that could produce a less sympathetic Syrian government to Iran.

It would also establish an Arab military presence in Syria designed to prevent Iran from extending its influence under the guise of securing the return of refugees.

For Assad, the carrot is tens of billions of dollars needed to rebuild his war-ravaged country and alleviate the humanitarian fallout of last month’s devastating earthquakes in northern Syria.

Hampered by sanctions, Assad’s Russian and Iranian backers don’t have the economic or political wherewithal to foot the bill.

China has made clear that its interests are commercial and further limited to aspects of Syrian reconstruction that serve its geopolitical and geoeconomic goals.

Assad was in Moscow this week to discuss trade and humanitarian aid.

The Syrian president’s rejection of a Russian request that he meet with his Turkish counterpart, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, suggests that he will be equally opposed to key elements of the Arab proposal.

The Syrian president said he would only meet Mr. Erdogan once Turkey withdraws its troops from rebel-held areas of northern Syria.

Even so, the Arab push potentially offers the United States and Europe the ability to strike a reasonable balance between their lofty moral, ethical, and human rights principles and the less savory contingencies of realpolitik.

The terms of the Arab proposal to allow Syria back into the international fold after a decade of brutal civil war that killed some 600,000 people, displaced millions more, and significantly enhanced Iran's regional footprint appears to take that into account.

According to The Wall Street Journal, the proposal offers something for everyone but also contains elements that are likely to be difficult to swallow for various parties.

While Mr. Al-Assad rejects the principle of political reform and the presence of more foreign troops on Syrian territory, legitimizing the regime of a man accused of war crimes, including using chemical weapons against civilians, is a hard pill for the United States and Europe to swallow.

However, it is easy to claim the moral high ground on the backs of thousands trying to pick up the pieces in the wake of the earthquakes.

The same is true for the plight of the millions of refugees from the war whose presence in Turkey and elsewhere is increasingly precarious because of mounting anti-migrant sentiment.

That is not to say that Assad should go scot-free.

Nonetheless, the failure to defeat the Syrian regime, after 12 years in which it brutally prosecuted a war with the backing of Russia and Iran, suggests the time has come to think outside of the box.

The alternative is maintaining a status quo that can claim the moral high ground but holds out no prospect of change or alleviation of the plight of millions of innocent people.

To be sure, morality is not a concern of Arab regimes seeking to bring Assad in from the cold. However, countering Iran and managing regional conflicts to prevent them from spinning out of control is.

Even so, the Arab proposition potentially opens a way out of a quagmire.

It would enhance the leverage of the United States and Europe to ensure that political reform is the cornerstone of Assad’s engagement with elements of the Syrian opposition.

In other words, rather than rejecting any solution that does not involve Assad's removal from power, the United States and Europe could lift sanctions contingent on agreement and implementation of reforms.

Similarly, the U.S. and Europe could make sanctions relief contingent on a safe, uninhibited, and orderly return of refugees.

However, there would be questions about the ability and willingness of Arab forces loyal to autocratic regimes to safeguard that process impartially.

U.S. and European engagement with Arab proponents of dealing with Assad would potentially also give them a seat on a train that has already left the station despite their objections.

Ali Shamkani, the Iranian national security official who negotiated the deal with Saudi Arabia in Beijing, was in the UAE this week to meet President Mohammed bin Zayed. There is little doubt that Syria was on the two men’s agenda.

Assad met this weekend in Abu Dhabi with Mr. Bin Zayed for the second time in a year and after traveling to Oman for talks with Sultan Haitham bin Tariq last month.

The Jordanian and Egyptian foreign ministers recently trekked separately to Damascus for the first time since the civil war in Syria erupted in 2011.

Perhaps, the most fundamental obstacle to the Arab proposition is not the fact that Syria, the United States, and Europe would have to swallow bitter pills.

The prime obstacle is likely to be the Arab proponents of the plan. The UAE, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, and Jordan are unlikely to stick to their guns in presenting the plan as a package.

Having taken the lead in cozying up to Assad, the UAE has since last year demonstrated that it is willing to coax the Syrian leader to back away from Iran at whatever cost to prospects for reform or the alleviation of the plight of his victims.

Saudi Arabia, like Qatar and several other Arab countries, initially opposed reconciliation but has since embraced the notion of rehabilitation of Mr. Al-Assad.

This puts the ball in the U.S. and European courts.

Much of the Arab proposition is about enticing the United States and Europe to be more accommodating and more inclined to a conditioned lifting of sanctions.

The problem is that Mr. Al-Assad is likely to call the Arab states’ bluff in the knowledge that Iran is his trump card.

A speedy U.S. and European embrace of the Arab proposition would hold Emirati and Saudi feet to the fire and put Mr. Al-Assad on the back foot.