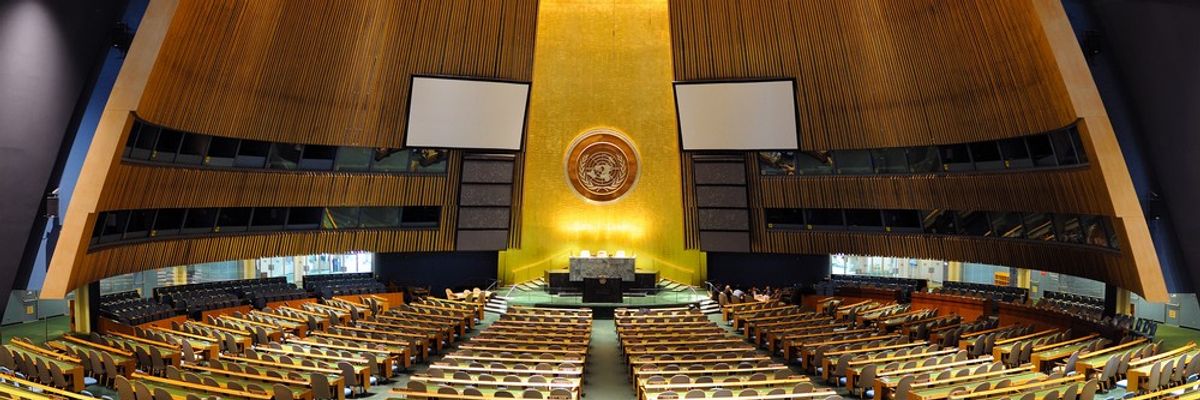

In his Wednesday address to the UN General Assembly, President Biden again called for a united global stance to isolate Russia because of its war of aggression against Ukraine.

“This war is about extinguishing Ukraine’s right to exist as a state, plain and simple, and Ukraine’s right to exist as a people. Whoever you are, wherever you live, whatever you believe, that should not — that should make your blood run cold.

That’s why 141 nations in the General Assembly came together to unequivocally condemn Russia’s war against Ukraine. The United States has marshaled massive levels of security assistance and humanitarian aid and direct economic support for Ukraine — more than $25 billion to date.

Our allies and partners around the world have stepped up as well. And today, more than 40 countries represented in here have contributed billions of their own money and equipment to help Ukraine defend itself. “

Such global unity has never existed, except in the fevered hopes of U.S. officials. Biden neglected to mention that virtually all of the 40 countries contributing to Ukraine’s defense are NATO members or other U.S. allies and security dependents. Support elsewhere in the world for sanctions and other components of its policy against Moscow has been notable by its absence.

Barely one month into the Ukraine war, Hudson Institute scholar Walter Russell Mead noted Washington’s lack of success in broadening the anti-Russia coalition beyond the network of traditional U.S. allies.

“The West has never been more closely aligned. It has also rarely been more alone. Allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization plus Australia and Japan are united in revulsion against Vladimir Putin’s war and are cooperating with the most sweeping sanctions since World War II. The rest of the world, not so much.”

Biden’s boast about 141 nations coming together “to unequivocally condemn Russia’s war” was a bit of an exaggeration. His comment referred to a resolution the UN General Assembly passed on March 2. It did demand “an immediate cessation of the hostilities by the Russian Federation against Ukraine,” but it was purely symbolic measure that did not require member states to do anything.

Despite the toothless nature of the resolution, five nations cast negative votes, and 35 nations, mostly in the Middle East and Africa abstained — an unsubtle diplomatic snub to the United States. The easy action would have been to vote for the meaningless gesture and placate Washington. That more than 20 percent of UN members opposed the measure or abstained was an early sign of trouble for Washington’s policy, not an affirmation of global unity supporting that policy.

Matters have not improved since then. Despite extensive diplomatic pressure from the Biden administration, key diplomatic and economic players — including Brazil, South Africa, and Saudi Arabia — have refused to impose sanctions against Russia. Most damaging, Asia’s two demographic and economic giants, India and China, have stubbornly remained on the sidelines.

Indeed, some early dissension was evident even within NATO. Hungary’s Prime Minister, Viktor Orban, made it clear from the outset that his country would not send weapons to Ukraine. Scorning the European Union’s solidarity with the United States regarding anti-Russian sanctions, Orban later stated that the EU had “shot itself in the lungs” by joining the U.S. crusade to coerce Russia — especially with the sanctions on natural gas and other energy supplies. That action, he warned, threatened to create a cold, dark winter and a nasty economic recession for European citizens.

Turkey’s deviation from the policy Washington is pushing is even greater than Hungary’s. Almost from the beginning, Ankara has given higher priority to ending the war in Ukraine as soon as possible rather than trying to coerce, weaken and humiliate Russia. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has repeatedly offered to play the role of mediator.

Turkey’s restlessness with the U.S.-NATO strategy has deepened over the months. In early September, Erdogan sharply criticized Turkey’s NATO partners for engaging in repeated provocations toward Moscow. Turkey has been attempting to bring both Russia and Ukraine to the bargaining table, and has been successful, at least in spurring grain shipments.

“As Turkey, we have always maintained a policy of balance between Ukraine and Russia. From now on, we will continue to follow that balanced policy,” he told reporters earlier this month.

The fissures between Washington’s policy preferences and those of its European allies show signs of widening. Under intense pressure from the United States, the G-7 adopted price caps on imports of Russian gas and oil in early September. Violators supposedly would be subject to sanctions. The measure was the ultimate exercise in counterproductive posturing. Putin responded by threatening to cut off all energy exports to the West, if the price caps violated existing contractual commitments.

At least 10 EU countries voiced objections to the new G-7 restrictions, and the EU ultimately backed away from adopting that course.

Biden’s UN speech did not enhance Washington’s bid for greater international support. He asserted that “if nations can pursue their imperial ambitions without consequences, then we put at risk everything this very institution stands for. Everything.” Biden was emphatic about the especially odious character of Russia’s assault on Ukraine:

“Russia has shamelessly violated the core tenets of the United Nations Charter — no more important than the clear prohibition against countries taking the territory of their neighbor by force.”

The delegates listening must have been astonished at the brazen hypocrisy. Whatever the possible validity of the humanitarian justification, NATO bombed Serbia without UN Security Council approval in 1999 and forcibly severed its province of Kosovo. NATO member Turkey has recently conducted airstrikes against Kurds over the border in Syria and has threatened a full incursion. It literally took portions of Cyprus in 1974. U.S. ally Israel seized and continues to occupy the West Bank and Syria’s Golan Heights. In condemning Russian aggression, Biden also apparently assumed that none of his listeners recalled the attacks by the United States and its allies on Iraq, Libya, and Syria to oust governments they opposed.

But leaders of countries around the world — and their populations — remember those events all too well. Washington’s arguments ring hollow, even if there was no cost to getting on the Western bandwagon. But as European countries are discovering, the loss of Russian energy supplies likely will lead to considerable suffering. Nations in Asia and Africa, facing the possible loss of both energy supplies and food shipments, are even less willing to antagonize Moscow.

For all of those reasons, Biden’s latest call for global unity against Russia will fail. The international community is not about to sign on to Washington’s hypocritical crusade.

Instead of continuing to exert intense pressure on reluctant countries to follow Washington’s policy lead, U.S. officials should listen more carefully and with greater respect to the criticisms and objections that they have made. Perhaps foreign leaders are detecting serious problems with the Biden administration’s approach that the president and his advisers fail to see. For example, it is unlikely that Washington fully anticipated the extent of Russia’s leverage on energy and food supplies or the extensive disruption to the global economy that the U.S.-led sanctions have caused. U.S. leaders need to relearn the art of diplomacy in dealing with allies and neutrals.

Administration officials also need to abandon the effort to force Russia to capitulate. Such an outcome is improbable, and the pursuit of that objective increases the risk that the Ukraine war will become a prolonged, very bloody stalemate. Washington’s strategy should be to facilitate negotiations between Kyiv and Moscow as soon as possible, even if the likely settlement will not fulfill the original U.S. and Ukrainian goals. Being a facilitator for peace would reflect genuine, constructive U.S. global leadership.