There is increasing talk about the United States getting more deeply committed to anti-Iran security arrangements on the side of Arab states of the Persian Gulf, especially Saudi Arabia, and Israel.

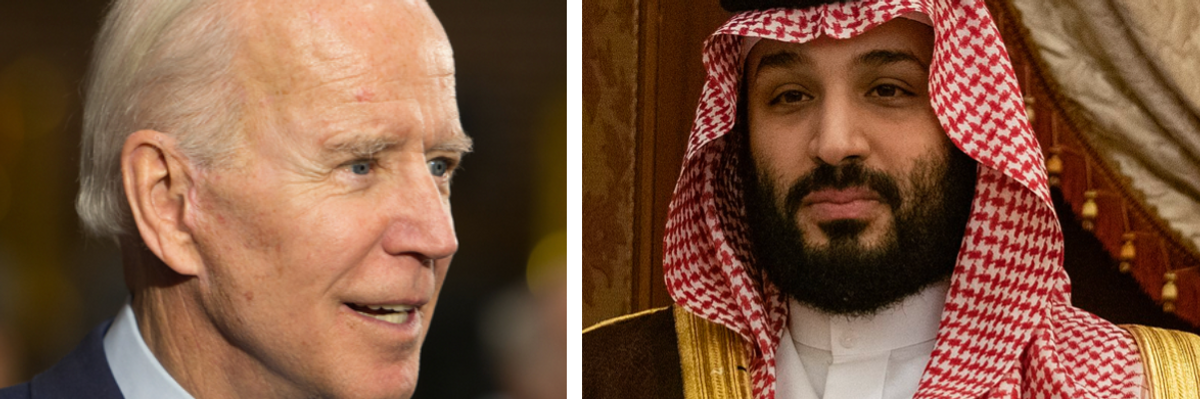

Legislation along this line has been proposed in Congress, and the Biden administration appears to want to take steps in this direction in connection with the president’s coming trip to Saudi Arabia and Israel. Doing so would be a mistake. Such a move lacks justification in terms of the security realities in the region and the nature and records of the regional states concerned.

To be clear, the present subject is not inclusive collective security arrangements such as the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Something like that actually would be useful in reducing tension and restraining conflict in the Middle East. Rather, what is being talked about is a security alliance, operating at least in certain functional areas such as air defense, which involves the United States taking sides in regional rivalries. In other words, something more like NATO than like the OSCE.

To justify U.S. participation in such an alliance — with all the commitments and risks that go along with it — requires at a minimum two basic conditions. One is a genuine military threat from whatever hostile power the alliance is aimed against, which cannot be countered without significant U.S. help. The other is that the regional side being helped has interests and values that are so much more congruent with those of the United States than are the interests of the opposing side that it is clearly a U.S. interest for the first side to prevail.

When NATO was established in 1949, these conditions were met (notwithstanding all the later legitimate post-Cold War debate about the roles and membership of NATO). The military forces of the Soviet Union, which had demonstrated their power in pushing back Nazi Germany in World War II, had overrun Eastern Europe and had the strength to push farther West. And survival of liberal democracy in Western Europe unquestionably was far more consistent with the interests and values of the United States than if the entire continent had come under the domination of a Stalinist dictatorship.

Neither of these conditions prevails in the Middle East. Regarding the first condition about a genuine military threat, the supposed threatener, Iran, is no USSR or even remotely close to being so. It is a mid-level power whose military has been weakened by decades of sanctions. Its air force consists mainly of equipment that belongs more in a museum than on the flight line and that would not be a match for, say, the air force of the United Arab Emirates. The most militarily powerful state in the Middle East is not Iran but instead Israel, even when considering only conventional forces and not nuclear weapons.

The other condition, regarding the interests and values of each side and what they mean for the United States, also does not prevail in the Middle East. Several specific criteria can be considered in this sort of evaluation. The following are the most pertinent ones, as applied to Iran and to the states President Biden is visiting and are touted as security partners: Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Non-aggression. Surely an important consideration in establishing any security arrangement is which states do or do not have a habit of using their military forces aggressively against foreign states. This consideration has become all the more important amid Russia’s war against Ukraine, in which aiding the Ukrainians is justified most persuasively as an upholding of the principle of non-aggression. In the last few years, the biggest instance of interstate aggression in the Middle East is the Saudi air war against Yemen, which has been the largest factor in turning that country into a humanitarian disaster.

The next biggest interstate aggression in the region during the same time frame is the Israeli air war against Syria, and against Iranian targets in Syria. Over a longer time period, Israel has done more than any other Middle Eastern state, except perhaps for Saddam Hussein’s former regime in Iraq, to throw its military weight around offensively. Israel repeatedly initiated major wars against Egypt, repeatedly invaded Lebanon and for years occupied a portion of that country, and staged more limited attacks against Iraq and against earlier targets in Syria. The offensive Israeli military operations have had numerous destabilizing effects, including stimulating the growth of Lebanese Hezbollah and accelerating an Iraqi nuclear weapons program.

Iran has not been doing anything of the sort. By far its biggest involvement in a foreign war was the eight-year conflict against Iraq, which began with unprovoked aggression against Iran by Saddam Hussein’s regime. The aid it gives to the Houthis, the de facto government over most Yemenis, pales in comparison to the Saudi military intervention in Yemen. Iran’s aid to Syria has been invited help to an ally in fighting opposition forces that have featured Islamic State and groups dominated by an al-Qaida affiliate.

Democracy. None of the three countries comes close to being a model democracy. Saudi Arabia is the least democratic, being a family-ruled monarchy in which free elections are unheard of. Current de facto ruler Mohammed bin Salman has been working to eliminate whatever checks and balances have existed within the family and is bringing Saudi Arabia closer to one-man rule.

Iran’s departures from democracy mainly involve the arbitrary disqualification by the unelected Guardian Council of candidates for public office. Despite this and other major defects, Iran at least has had, unlike Saudi Arabia, elections to the presidency and the legislature that have actually mattered.

Israel uses democratic procedures within the dominant portion of its population but does not apply them to the 5.3 million Palestinian residents of territories that Israel rules and treats for whatever purposes it wants as an integral part of Israel. Those residents have no political rights, including any right to vote for or against the government that rules their homeland.

Religious freedom. There is no religious freedom in Saudi Arabia, where the open practice of any religion other than Islam is prohibited. Both Iran and Israel permit the practices of religious minorities, but both preserve a privileged position for the dominant state religion: Shia Islam in Iran, and Orthodox Judaism in Israel. Israel has enshrined in legislation the doctrine that “the right to exercise national self-determination” in Israel is “unique to the Jewish people.” The power of the Orthodox rabbinate is reflected in matters such as marriage, with there being no such thing in Israel as inter-faith or civil marriages.

Other human rights. All three states are human rights abusers. Iran’s most salient offenses involve unlawful detention of dissidents or of innocent people used as trade bait in international disputes. The long list of offenses by Saudi Arabia in the State Department’s human rights report on that country begins with “executions for nonviolent offenses; forced disappearances; torture and cases of cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment of prisoners and detainees by government agents; harsh and life-threatening prison conditions; arbitrary arrest and detention…” As for Israel, human rights organizations including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and the Israeli organization B'Tselem have thoroughly documented the human rights abuses associated with the apartheid system Israel maintains in the occupied territories, including indefinite detentions, demolition of homes, and frequent use of lethal force.

Terrorism. All three states have been at least as much a part of the problem of terrorism as of solutions to combat it. Iran has backed away from its more prolific use of terrorist tactics, especially overseas assassinations of dissidents, during the early years after its revolution. Now most of its attempted use of such tactics is in direct response to use of similar tactics by Israel. That response has been largely ineffective to the point of incompetence, so much so that the intelligence chief of the Revolutionary Guard was fired as a result.

In contrast, Israel has a well-honed and much-used apparatus for conducting overseas assassinations. Far from backing off, recently it has stepped up its overseas clandestine assassinations and sabotage, chiefly against Iranian targets. This is in addition to the stimulus that Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory has given to violent anti-Western extremism.

Direct state terrorism by Saudi Arabia took its most salient form with the assassination of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in Turkey in 2018. But probably an even bigger influence on the kind of terrorism that has most affected U.S. interests has been the Saudi state’s promotion of the extremist Wahhabist ideology that has inspired many recruits to the likes of al-Qaida and Islamic State.

Great power relationships. None of the three states has been especially helpful to the United States regarding their relations with Russia and China. Iran has been reaching out to both Russia and China — unsurprisingly, given how U.S.-imposed sanctions have given Tehran few alternatives. Saudi Arabia was already playing an uncooperative great power game back in the 1980s when it secretly purchased intermediate-range ballistic missiles from China. Today, Riyadh takes a soft line toward Russia despite the invasion of Ukraine. Israel also has been rather uncooperative regarding the war in Ukraine, evidently valuing its relations with Russia — and its freedom to keep launching attacks in Syria without Russian interference — over whatever sense of gratitude one might think that $3.8 billion in annual U.S. aid would buy.

Oil. Oil output ought not to be a general consideration in making security commitments, but it evidently is high on Biden’s agenda for his talks with the Saudis and may be part of any deal he makes with them. He is unlikely to get much on this front no matter what he offers, for reasons involving production capacity of Saudi Arabia as well as the UAE. But as the United States tries to square the circle of limiting Russia’s oil revenues while holding down the price of gasoline for American drivers, it seems to be forgotten that there is another producing country on the other side of the Persian Gulf with lots of oil to sell.

Iran, whose exports of oil have been limited by sanctions, has the fourth largest petroleum reserves in the world. Iranian oil officials say Iran could double its exports to help meet global demand and could reach its maximum production capacity within two months after easing of the relevant sanctions. Biden probably could get more non-Russian oil on the world market and thereby help get those gasoline prices down by swiftly returning the United States to compliance with the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the agreement that limited Iran’s nuclear program, than by giving the Saudis concessions in some anti-Iran security arrangement.

***

In sum, there is no legitimate case for the United States making new commitments and assuming additional costs on behalf of one side of the Middle Eastern rivalry that involves the countries on Biden’s itinerary. Such a taking of sides does not involve sticking up for interests that are conspicuously more in line, or more in line at all, with American’s interests than are the interests on the other side of the rivalry. The side-taking instead results from the firmly engrained national habit, dating back to the earliest days after the Iranian revolution, of thinking of Iran only as a permanent and implacable enemy, and from the usual impact that the preferences of the Israeli government have on American politics.

Any new U.S. security commitments along the lines being talked about would risk dragging the United States into conflicts that stem from the ambitions and objectives of regional players and not from U.S. national interests. Such commitments also would encourage those players to sustain regional conflicts and would reduce the incentive for them to find ways to live in peace with their neighbors.