Colombia’s presidential election is headed to a runoff on June 19. It’s impossible to predict who will govern from 2022 to 2026, but striking change is certain. For the first time in the modern history of Latin America’s third-largest country, the chosen candidate of Colombia’s entrenched, established political elite is not one of the finalists.

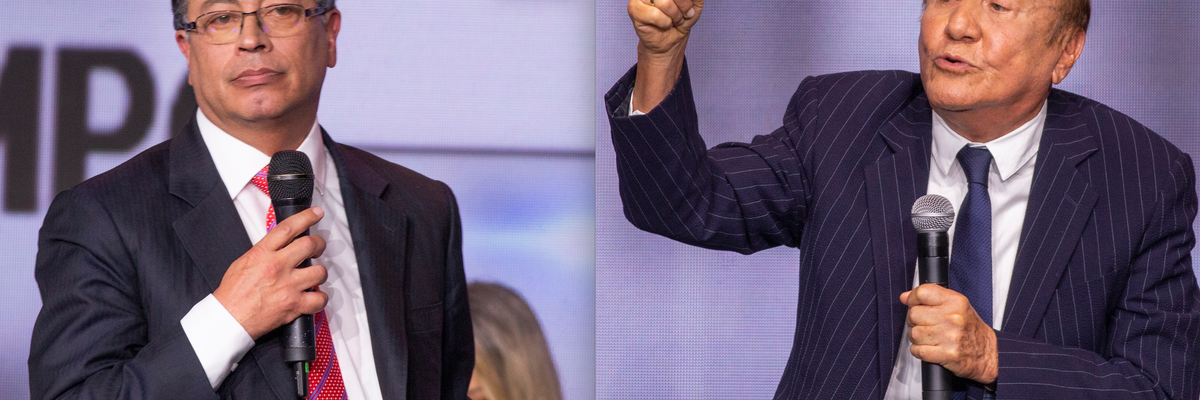

Colombians are exhausted by the pandemic, rising poverty and inequality, rising crime and proliferating armed groups, and a sitting government that has failed to convey empathy. In May 29 first-round voting, 40.3 percent backed Gustavo Petro, the first viable left-of-center candidate in at least 80 years in a country where reformist candidates have often been assassinated.

Though he was filling plazas and getting much media coverage, polls had correctly shown Petro, a former guerrilla and former mayor of Bogotá, unlikely to hit the 50 percent threshold needed for a first-round victory. Surveys had pointed to Petro facing in the second round, and probably beating, Federico Gutiérrez, the candidate backed by the party of Colombia’s current president, Iván Duque, an unpopular conservative.

That’s not what happened: Gutiérrez finished third, and Petro will instead face another pro-change, “outsider” candidate. Rodolfo Hernández, an irascible 77-year-old former mayor of Colombia’s sixth-largest city, took 28.2 percent. A wealthy businessman running without a political party and appearing more often on Tik-Tok and other platforms than in person, Hernández appealed to Colombians opposed to Petro’s politics but unhappy with the status quo. He surged late in the polls, buoyed by a folksy, gaffe-prone populist style and a single-minded anti-corruption message (although contracting irregularities during his mayoral administration are under investigation).

Petro’s lead and Hernández’s surge dealt a heavy blow to Colombia’s traditional political machines, including that of once-dominant ex-president Álvaro Uribe (2002-2010), a conservative whose chosen candidate (including himself) had made it to the final round of every election since 2002, losing only once. Whoever wins on June 19 will not be beholden to Colombia’s mainstream parties, though they still have many congressional seats. And very notably, regardless of outcome, Colombia’s next vice president will be a Black woman: either social movement leader Francia Marquez (Petro) or academic Marelén Castillo (Hernández).

The math right now favors Rodolfo Hernández. His share of valid votes on May 29, plus those for Gutiérrez, yields an “anybody but Petro” vote of as much as 54 percent. A first poll, released June 1, showed Petro and Hernández within the margin of error, with Hernández slightly ahead, and a large number of undecideds (14 percent). A second, without undecideds, gave Hernández a 52-45 margin.

Though a vote between two “change” candidates with strong populist tendencies, June 19 will not be a contest between left and right: to view Colombia’s election that way is to misunderstand it. Hernández, in a clear effort to shed the “right-wing” tag, laid out a May 30 tweet thread of political proposals so centrist, even leftist on some issues, that Petro accused him of “incorporating my proposals":

Both promise to implement the 2016 peace accord with the FARC, which Uribe and his supporters opposed. Petro’s program discusses in greater detail how he would implement it, including gender and ethnic priorities.

Both promise to pursue negotiations with Colombia’s remaining 50-plus-year-old guerrilla group, the regionally strong National Liberation Army (ELN).

Both would re-establish relations with the Nicolás Maduro regime in Venezuela, a likely blow to the alternative opposition government of Juan Guaidó, whom both Bogotá and Washington currently recognize as Venezuela’s president.

Both are very critical of drug policy as practiced for the past half-century. Hernández told the U.S. ambassador that he favored legalizing drugs when they met in January. Both would seek to legalize recreational cannabis, and a harsh U.S.-supported policy of eradicating coca by spraying herbicides from aircraft, suspended for health reasons since 2015, would not restart.

Both candidates oppose fracking, support abortion rights (recently legalized by a Constitutional Court decision), and support LGBTQ rights, gay marriage, and adoption by gay couples.

Both say they support the right to social protest, including the national strike that paralyzed Colombia for weeks in April and May 2021. And both are sharply critical of Uribe, the hardline former president whom Colombians associate with important security gains, but also with human rights violations and ethical lapses.

The left-right lens, then, is of little use to understand what is happening. Gustavo Petro’s positions are traditionally leftist, but it remains unclear whether Petro would govern as a social democrat or a populist strongman. Hernández is friendlier to big business, but the positions listed above show more ideological flexibility than we’ve seen from right-populists like Jair Bolsonaro or Donald Trump. Rather than calling him the “Colombian Trump,” it makes more sense to compare Hernández to semi-autocratic Latin American populists who don’t easily fit left-right pigeonholes, like Mexico’s Andrés Manuel López Obrador or El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele.

Whoever wins, then, Colombia’s next president will be a leader who seeks to appeal directly to the people, who fights often with the media, and who is unlikely to uphold long-held norms and fragile institutions. The next leader will bristle at democratic checks and balances; both have floated the idea of using emergency powers. He will inveigh against enemies: for Petro, those are Colombia’s traditional elites; for Hernández, they are those he views as corrupt—or, alarmingly, the Venezuelan migrant population, who have been the subject of some xenophobic comments.

These are all elements of what we might call the “populist playbook,” a fixture of declining 21st century democracies worldwide. Colombia’s next president could be popular and transformative, but the country may become even less democratic.

This poses challenges for the United States. Democratic and Republican administrations alike have spent 25 years, and over $13 billion, building a “special relationship” with Colombia — especially Colombia’s security forces. President Joe Biden is fond of calling Colombia "the keystone of U.S. policy in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Washington is concerned about losing influence in the Western Hemisphere to China and other great-power rivals.

Washington is about to find that it built a special relationship only with a small segment of Colombia — urban elites, the armed forces, business associations — leaving it unprepared to work with a government whose base is elsewhere, in organized civil society and among disgruntled middle classes, poorer Colombians, and Afro-descendant and Indigenous Colombians. Regardless of who wins, the U.S.-Colombia relationship will probably remain cordial overall, but the road ahead will be very bumpy.

Both candidates’ views of Venezuela relations and of drug policy — especially forced crop eradication and extradition — could set them on collision courses with the Biden administration and with congressional Republicans. Petro’s critical view of free trade and foreign investment, and a likely desire to loosen the U.S.-Colombian military partnership, would provoke hostility in some quarters in Washington. The result could be nasty words, reduced diplomatic presence, reduced assistance, and perhaps an even tighter embrace of Colombia’s out-of-power business and political elites.

Washington’s relationship with Colombia might come to look like it does right now with other populist or authoritarian-trending governments in the region (other than the hard-left ones — Cuba, Nicaragua, Venezuela —w ith which relations are fully hostile). If so, U.S. officials will avoid airing most disagreements in public. They will prefer to emphasize areas of cooperation, as they do today on migration with Mexico and Central America, or on military ties with Brazil.

U.S. officials will seek to relate to some institutions even as they stand apart from political leaders. In Brazil, El Salvador, and Guatemala, for instance, the U.S. Southern Command continues a robust schedule of military engagements even as relations with Presidents Bolsonaro, Bukele, and Giammattei are distant. It is easy to imagine a scenario in which the military-to-military relationship becomes the U.S. government’s closest interaction with Colombia.

The next, immediate challenge for U.S. policy — and for international diplomacy overall — is coming on June 19. If, as appears likely, the candidates are within a few percentage points of each other, the chance of one crying “fraud” and rejecting the result are high. If Hernández rejects the result, he could have powerful business interests and political bosses behind him, and perhaps even factions of the security forces. If Petro rejects it, street protests could grind the country to a halt, and perhaps again meet with a violent police response.

If this happens, the U.S. government, along with the OAS and all friends of Colombia, must work to defuse violence and channel tensions into dialogue. That means basing all public statements on established facts, not desired outcomes. It means condemning behavior that violates human rights, which the Biden administration was slow to do during the 2021 national protests.

As their choice of two outsider candidates shows, Colombians are on edge right now. The diplomatic goal must be to amplify what is true and de-escalate quickly. Only then can we shift to concerns about policy and populism.