It is a tradition, a ritual even, that on Memorial Day, we say, “never forget.” It is brandished in the stark pledge of “you are not forgotten” on the black and white POW/MIA flag, first flown among veterans after the Vietnam War to call attention to American prisoners of war and missing in action. That flag, like the words, are now universal for honoring the memory and sacrifice of all men and women in our wars, the living and the dead.

We “remember” in many different ways, especially on this holiday, but the greatest manifestation of that recognition, the persistence in “never forgetting,” came last week when the Senate came to a bipartisan agreement over sweeping measures that will finally give veterans suffering from toxic exposures broad, unrestricted access to health care and disability assistance.

The Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act (or PACT Act) passed the House in March. Republicans, staring at the $200 billion (over 10 years) price tag, had initially resisted. Then on Thursday, Senators Jon Tester (D-Mont.) and Jerry Moran (R-Kansas) announced that they believed a new, and actually bigger bill than the House version, could pass Congress.

This is a game-changer. Iraq and Afghanistan veterans have been struggling for nearly 15 years against the military and VA systems for recognition. In that time, many died or became too ill to continue the advocacy. Never forgetting, others picked up the mantle and drove on, making toxic exposure from “burn pits” on overseas bases during the wars — which many blame for a range of severe lung, heart, skin conditions, as well as cancer – a national cause.

“This is huge,” said Jen Burch, an Air Force veteran who worked as a medic in Afghanistan from 2010 to 2011, and now works with the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America. She added that this is “the most comprehensive legislation” to date and “will save countless lives by providing health care and benefits to take care of veterans who become ill and ensure their families will be supported as well.”

So what would the legislation do? Among a host of other things, it more than doubles the number of “presumptions” to 23. These are conditions and illnesses that the VA recognizes as service connected, more specifically, the result of exposure to the massive open air garbage pits that were running on the massive forward operating bases in Iraq and Afghanistan. Veterans suffering from these specified conditions will automatically qualify for full healthcare and compensation.

Up until now, somewhere in the range of 80 percent of veterans who have attempted to get full benefits for these illnesses have been turned away, said Burch, who tells Responsible Statecraft that she is living with a rash of ground glass nodules on her lungs that need to be routinely checked, as well as Restrictive Lung Disease, which causes her shortness of breath. She doesn’t think sick veterans should have to struggle against the VA just to get what the government promised them — “the pact” — when they signed up for duty.

It is difficult to encapsulate the breadth and scope of this problem in today’s veteran cohort. There are some three million Iraq and Afghanistan era vets. Tens of thousands of them cycled through the FOBs over the course of a decade and slept and worked around the pits, which were two to three football fields wide. In them, some 410 tons of garbage were tossed each day. There were no filters or regulations on how or where the pits, run by private contractors like KBR, burned. (Sick veterans tried to sue KBR, a subcontractor of Halliburton, but lost after several appeals). As a result, massive black plumes often rose above the installations as everything from batteries, rubber tires, styrofoam, plastics, human waste and even body parts burned together down below.

Vets later recalled that new denizens of the FOBs would get what they called “Iraqi crud” in the first weeks, coughing up black goo. Others lamented they were never issued simple masks when working to dump waste into the pits. For her part, Bucha said she exercised by running around the pit area in Kandahar where she was stationed. By the time she got home she couldn’t run at all.

The military knew as early as 2006 that the carcinogens released in the air from this toxic brew was a danger to everyone there and tried to hide it. But as veterans began coming home with strange ailments, hobbled by severe respiratory problems, skin lesions, and the like, they started talking with each other in online forums. Reporters like Kelly Kennedy, herself a Persian Gulf War veteran, began investigating and writing about it and questioning the VA and military directly. The burn pits were eventually shut down by Congress but the damage was already done.

Young veterans started dying from rare cancers, like the president’s son Beau Biden. And they are still dying. Kate Hendricks Thomas, 42, a staunch advocate for toxic exposure recognition, succumbed to Stage 4 breast cancer in April. A Marine, she served in Fallujah in 2005 and like Burch, had run her daily laps around the burn pit.

“They said it looked like I had been dipped in something,” Thomas told ABC News in 2021 about when she was first diagnosed at the age of 38. “I had metastases throughout my skeletal system from my skull to my toes.”

In 2014 the VA launched the Burn Pit Registry to gather data from veterans who may have been exposed and suffering from illnesses. As of September 2021, the latest figures available, 260,992 veterans had volunteered their information on the registry.

Of course, our Iraq and Afghanistan veterans are not the first to have come home with unexplained maladies, some which don’t present themselves until 5, 10, even 50 years after service. Vietnam veterans have had to fight each step of the way to have a host of illnesses and cancers tied to their exposure to Agent Orange recognized. Persian Gulf veterans suffer from illnesses tied to a cocktail of exposures from their time in Iraq in 1991. The PACT Act offers relief to them, too.

Kennedy is now the managing editor of the War Horse, a non-profit news organization dedicated to training veterans as journalists and reporting news related to the “human impact of military service,” according to founder and Afghanistan veteran Thomas Brennan. She said years of private medical research confirming the toxic exposure, combined with the awareness spread by veterans advocates and importantly, national figures like comedian Jon Stewart, broke the logjam politically and forced Washington to respond.

“All of these pieces (in the PACT Act) are hugely important to the veterans and families because they can not only get help and benefits, but also because they know their suspicions are legitimate,” she told Responsible Statecraft. “The acknowledgment is so important for mental health, as well as physical health.”

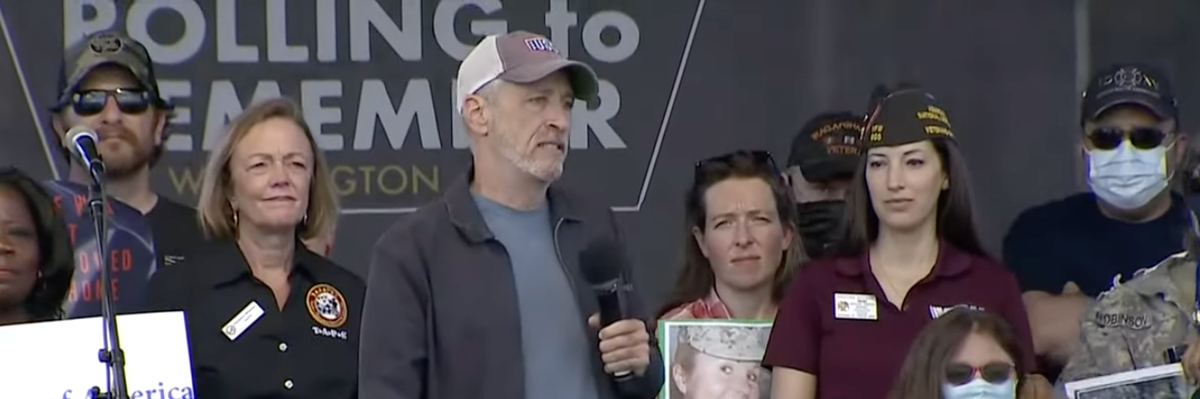

“Never forget.” For 40 years this was the overriding theme of the Rolling Thunder rallies in Washington over the Memorial Day holiday. This year is no different, as thousands of motorcycles rolled into the national capital this weekend from all across the country for three days of events. On Saturday they gathered at RFK Stadium in a call to action to prevent veteran suicides, followed by a rally to urge the Congress to pass the PACT Act. Stewart was on hand to lend his star power to the proceedings. He likened the effort to get burn pit legislation to passed Sisyphus rolling a boulder up a mountain, with all of the groups and players “putting their hand on it” to reach the top.

“Today we need everyone to put their hands on that boulder and put it over that mountain,” he told the crowd Saturday.

Mental health among active duty and veterans remains a persistent and complex challenge, as War Horse has reported on its own pages. In many cases, the lack of affordable, accessible healthcare can easily cause intractable feelings of isolation and despair.

“We have to be our advocate, doctor, and lawyer and then take all of our evidence and build a case to present to the VA,” noted Burch. “Imagine getting the courage to do all the work and pay out of pocket for many costly exams just to get denied. And then you wonder why suicides are still a problem. When veterans are denied for invisible injuries, it can go to their heads.”

It shouldn’t be so. We all have an obligation to hold elected officials and our institutions — which have taken a big hit on the trust charts in recent years — to the compact they made with servicemembers. If they are to fight their wars, the government needs to take care of them when they come home. What better day than today to remember that.