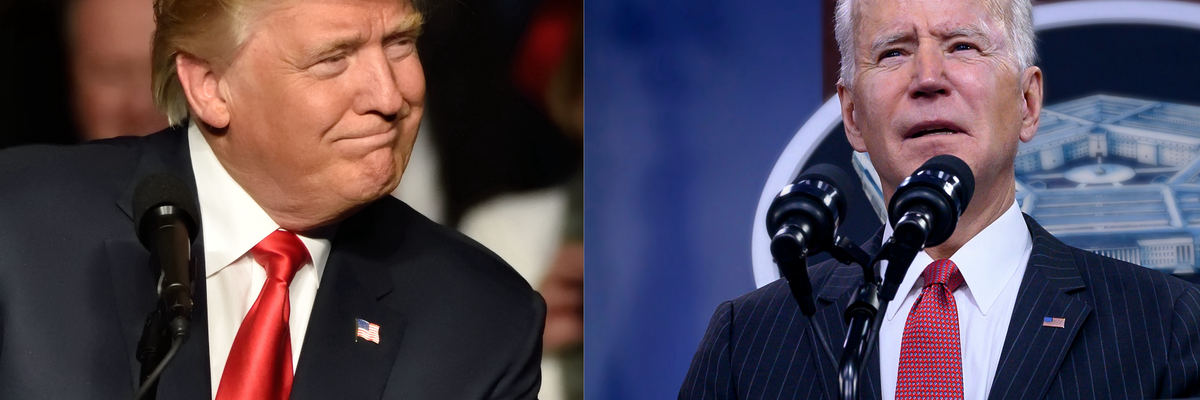

A year ago, Tehran and Washington began diplomatic efforts to revive the 2015 nuclear deal, which the Trump administration had sabotaged. The last 12 months of intense shuttle diplomacy by European governments have helped Tehran and the Biden White House agree on the technical steps needed to bring both sides back into compliance with the deal. Yet, Iran and the United States still find themselves in a standoff over political issues: the latest hot potato is what to do about the foreign terrorist organisation (FTO) designation of Iran’s Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) imposed under Donald Trump.

I will spare readers the long list of reasons as to why the 2015 nuclear deal is the best one on offer –the bottom line is that it provides a verifiable path to stop, and quickly react to, a potential Iranian march towards a nuclear bomb. This deal is not perfect, and there is no doubt that political decision-makers in both Iran and the US will face political heat for returning to it. But they are heading this way because its terms remain the best compromise on offer. And, in any case, behind the scenes those in charge in Tehran, Washington, and European capitals know their respective plan Bs look hideous.

Given this, it would be foolish for Washington to jeopardise the opportunity to contain Tehran’s nuclear programme over the lifting of what is a largely symbolic designation of the IRGC. US officials have repeatedly outlined that the IRGC will remain on a long list of sanctions that make it highly unlikely that its economic operations would attract new business. And, with its latest sanctions against Iran’s ballistic missile programme, the Biden administration has demonstrated it can walk and chew gum at the same time. Moreover, the FTO decision has done little to secure US interests: in fact, US officials have admitted that, since the designation, attacks by Iranian-backed groups in the region have spiked by 400 per cent. If the diplomatic track fails now, the IRGC is likely to be even more assertive in the region with an expanding nuclear programme at its disposal.

Iran has long maintained that, as a matter of principle and national pride, it wants this designation against a crucial part of it armed forces removed before returning to the nuclear deal. This should not be a surprise to the US administration. The struggle has been over what Washington can get in return from Tehran – and whether Joe Biden is prepared to take the ensuing criticism.

The US should not expect a big public gesture from Iran in return for lifting the FTO designation. For example, Iran is likely to reject proposals to state, publicly, that it will not take revenge for the assassination of General Qassem Soleimani during the Trump administration. The US remains concerned that Iran may carry out a counter-assassination against high-level former officials involved in the decision to kill Soleimani. Yet there is considerable worry in Iran that such a public pledge would set a dangerous precedent for the US and Israel to carry out future assassinations with no cost.

Tehran believes it has already conceded on some of its critical opening negotiating terms, such as seeking reparations from Washington for the billions of dollars’ worth of trade it lost as a result of the US walking out on a deal endorsed by the United Nations Security Council. Iran has also seemingly stepped back from pressing for written guarantees that a future American president would not withdraw from the agreement again.

The reality is that Biden will face opposition in Congress, and political backlash from Israel, no matter what kind of deal he reaches – purely because he is doing a deal with the Islamic Republic of Iran. For the US president, the longer he delays a final call, the closer he gets to the midterm elections in November, when his appetite for upsetting hawkish Democrats in Congress will shrink even further. In the meantime, Iran’s nuclear programme and knowledge continues to expand. With the Ukraine conflict already a geopolitical hotspot for the West, this is no time to add more crises to the mix by opening a new nuclear front in the Middle East that is likely to be met with an Israeli military response.

For Iran, delaying the return to the nuclear deal comes with a high price tag in terms of opportunities lost for its economy. In Tehran, power is now largely concentrated in the hands of the conservative political faction, which is eager to show it can manage the economy better than what its members view as their naive pro-Western predecessors. But, after almost a year in office, President Ebrahim Raisi’s government has been unable to substantively improve the economic conditions of ordinary Iranians.

The Ukraine conflict has also ignited internal debate in Iran over how to best to protect its national interests. In sharp contrast to its competitors in the Arab world, the stalemate over the nuclear deal means that Iran cannot take full advantage of high energy prices following Western sanctions against Russia. China has continued to buy Iranian oil despite US sanctions – but it has done so on the cheap. So long as Iran remains in the US sanctions box, it cannot find more buyers for its oil – such as South Korea, India, and European countries looking to reduce their dependence on Russia energy. Nor can Iran get free access to payment for its oil so long as US secondary sanctions choke up global financial transactions with the country.

European parties to the nuclear deal need to double down on pushing both Tehran and Washington to clear the last political hurdle. A number of reasonable compromises are in circulation. One suggestion reportedly under review is to remove the IRGC’s FTO designation but keep on the list its elite Quds force, which carries out operations in the Middle East. Another pathway could come at the UN Security Council, which endorses the JCPOA under resolution 2231. As part of a US return to the nuclear deal and the removal of the IRGC’s FTO designation, a side-commitment can be publicly issued by all parties to the nuclear deal at the Security Council level stating that UNSC permanent members and Iran will de-escalate military tensions in the Middle East.

Such a commitment would help the US reduce its military footprint in the Middle East, while cooling tensions can open up greater space for regional talks. There is no way to guarantee this de-escalation will last – the same way that there is no way to guarantee that this or a future American administration would not U-turn on the JCPOA as Trump did. In coming to a final deal, Iran and the US will need to accept these realities and exercise political will.

The core substantive differences on how to implement the nuclear deal have now been resolved. The parties even managed to keep the negotiations on track after Russia – a key member of the deal – almost brought the talks to a halt following the fallout with the West over sanctions linked to the Ukraine war. The longer Washington and Tehran wait, the more susceptible the process becomes to spoilers, and the more each side feels it cannot give an inch to save face domestically.

It is time to replace the JCPOA with JDIA: Just Do It Already.

This article was republished with permission from the European Council on Foreign Relations.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org