The Russian assault on Ukraine has stirred so much emotion, consumed so much bandwidth, and elicited so much anger at Vladimir Putin’s regime that those who have other agendas to pursue are strongly tempted to somehow link those agendas to the current crisis.

An especially strained example of this comes from those who oppose any diplomatic agreements with Iran and have tried to destroy the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, the multilateral accord that severely restricted the Iranian nuclear program. Their efforts no doubt are spurred in part by reports that negotiations in Vienna on restoring compliance with the JCPOA may be close to reaching agreement.

The attempts at linkage by the JCPOA opponents center on the fact that the Russian government has been involved in both the original negotiations that produced the JCPOA and the current talks on restoring compliance. Sometimes the assertion is that the Biden administration is determined to restore the JCPOA, is dependent on Russia for doing so, and therefore will not stand up to Russia for its offenses in Ukraine — never mind how much this assertion is at odds with what the administration already has done in responding to the Russian aggression. Sometimes the argument is that because Russia is involved, restoration of the JCPOA would somehow be a “win” for Putin.

But mostly this whole rhetorical line is just crude guilt by association — the notion that anyone doing business with the present Russian government must be on the wrong track. Here’s what Mark Dubowitz — who has made sabotage of the JCPOA or any other agreement with Iran a raison d’etre for himself and his organization, the Federation for Defense of Democracies — says: “The Biden administration is days away from signing a deal with Iran negotiated by Putin. Let that sink in."

One of the remarkable things about this whole rhetorical line is that, while it is a puerile way of arguing no matter who is the target, the idea of supposed deference to Putin could be applied much more readily and convincingly to the U.S. president who preceded Biden. That’s the president who repeatedly said that the JCPOA was awful, who reneged on all U.S. obligations under the JCPOA, who tried to use sanctions to make it as difficult as possible for a successor administration to return to compliance, and in short did everything he could to trash the agreement.

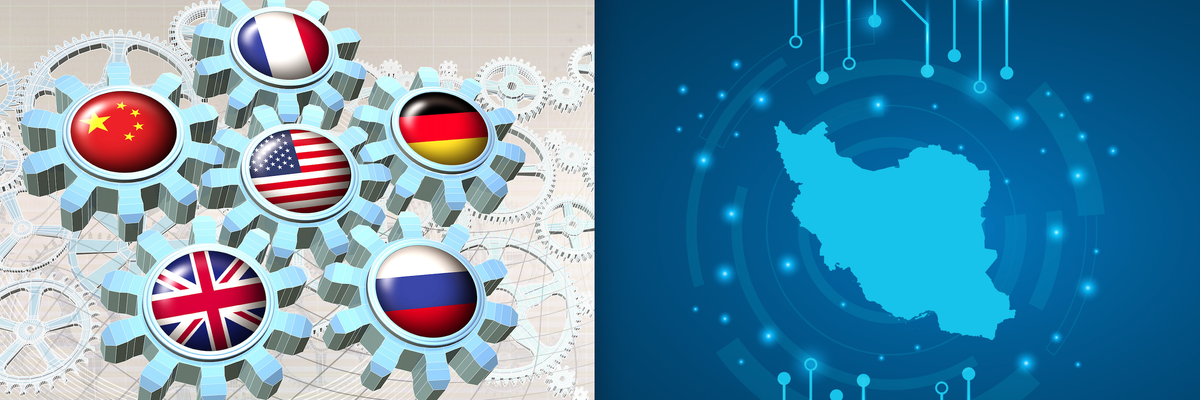

The JCPOA is a multilateral accord in which the United States, Russia, China, Britain, France, Germany, the European Union, and Iran all have been involved. Russian diplomats participated alongside their counterparts from the other parties, but the original agreement was not “negotiated by Putin,” nor will an agreement on restoring compliance. If any product of multilateral diplomacy is to be considered tainted merely because Russian diplomats are involved, that would apply to countless resolutions of the United Nations Security Council, international conventions, and other multilateral diplomatic instruments, many and probably most of which are indisputably in U.S. interests.

The Europeans, Russians, and Chinese have worked largely in concert throughout all the diplomacy involving the JCPOA. So did the United States, except when it became the odd man out by reneging on the agreement in 2018.

All the parties participated, and are participating in the restoration talks, because they recognize that the JCPOA has been in the interests of nuclear nonproliferation and reduction of conflict in the Middle East. The members of the Security Council who unanimously approved Resolution 2231, which is the international endorsement of the JCPOA, recognized that as well.

Russia shares these interests. Its participation has not been a favor to the United States or to any U.S. administration. Russia doesn’t want to see a new nuclear weapons state a short distance from its southern border.

Diehard opponents of the JCPOA are resorting to the silliness of trying to smear the JCPOA with the mud of Putin not only because a new agreement might emerge any day from the talks in Vienna but also because they don’t have any real evidence to support their opposition. The direction in which the experience of the past seven years points is indisputable. Seldom do international relations provide as stunning a contrast as the one between the three years the JCPOA was in effect and successfully limited Iran to a small fraction of the fissile material it previously had, and the complete failure of the subsequent period of “maximum pressure,” which has seen the Iranian stockpile grow to several times what it was under the JCPOA and reduce the “breakout time” to produce a bomb’s worth of fissile material from about one year to only about a month.

The war in Ukraine may indeed have ill consequences that involve Iran, not in the way that the fatuous rhetoric of the JCPOA opponents suggest but rather in being a diversion of attention that may tempt other would-be aggressors to act. This is often mentioned in connection with China and the Far East, but it also could apply to the Middle East and especially Israel, which repeatedly threatens to attack Iran. Israel’s history may give its leaders some ideas in this regard. When Israel invaded Egypt in 1956 to begin what would become known as the Suez crisis, the invasion followed by a few days the outbreak of a revolution in Hungary that the Soviet Union’s Red Army would later crush. The coincidence in time of the two crises made it difficult for the world community to respond to either one with its full attention. Israeli decisionmakers contemplating a new attack in the Middle East may see the new Russian military operation in Europe as having similar diversionary value.

The long subsequent history of Israel’s attacks on its neighbors includes its current sustained campaign of aerial attacks on Syria. It is here — not the negotiations on a restored JCPOA — where one can find a going soft on Russia because of a need for Moscow’s cooperation. What little criticism the Israeli government has made of the Russian invasion of Ukraine has been remarkably restrained. The main apparent reason is that Israel wants to continue its bombardment in Syria without any interference from the Russian presence there.