On January 12, the Washington Post’s John Hudson published an article detailing the Biden administration’s decision to continue supporting French counterterrorism operations in the Sahel region of Africa — despite the unsuccessful nature of those operations over the last decade.

After deploying troops to northern Mali in 2013 to chase jihadists out of major cities, the French transitioned to a region-wide counterterrorism mission, Operation Barkhane, in 2014. Barkhane’s future is unclear amid a partial force reduction and French President Emmanuel Macron’s June announcement that the mission was ending. Despite those moves, Barkhane continues to conduct operations at a fairly rapid tempo, and the French are simultaneously building up a pan-European special forces unit called Task Force Takuba. French officials had also threatened to cut off operations in Mali if Malian authorities brought in Russian assistance in the form of Wagner Group mercenaries. The junta there had approached the Russians after the French announced it would be reducing its own troops there under Barkhane by half.

The Biden administration’s decision to continue providing logistical and intelligence support for French operations in the Sahel, Hudson reports, was undertaken as part of a wider diplomatic overture following a completely unrelated U.S.-French dispute over who would sell submarines to Australia. The U.S.-United Kingdom-Australia trilateral security pact known as AUKUS, announced in September 2021, involves U.S. and UK support to Australia for nuclear-powered submarines— an agreement that undercut a 2016 French-Australian contract for diesel-electric submarines. In response to AUKUS, France recalled its ambassador from Washington for what may have been the first time ever. French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian called the pact — and what the French saw as American and British undercutting of core French economic interests — “unacceptable behavior between allies and partners.” The resulting tensions left Washington scrambling to find other areas where they could mollify the French, and its decision to provide assistance in the Sahel appears to be one of them.

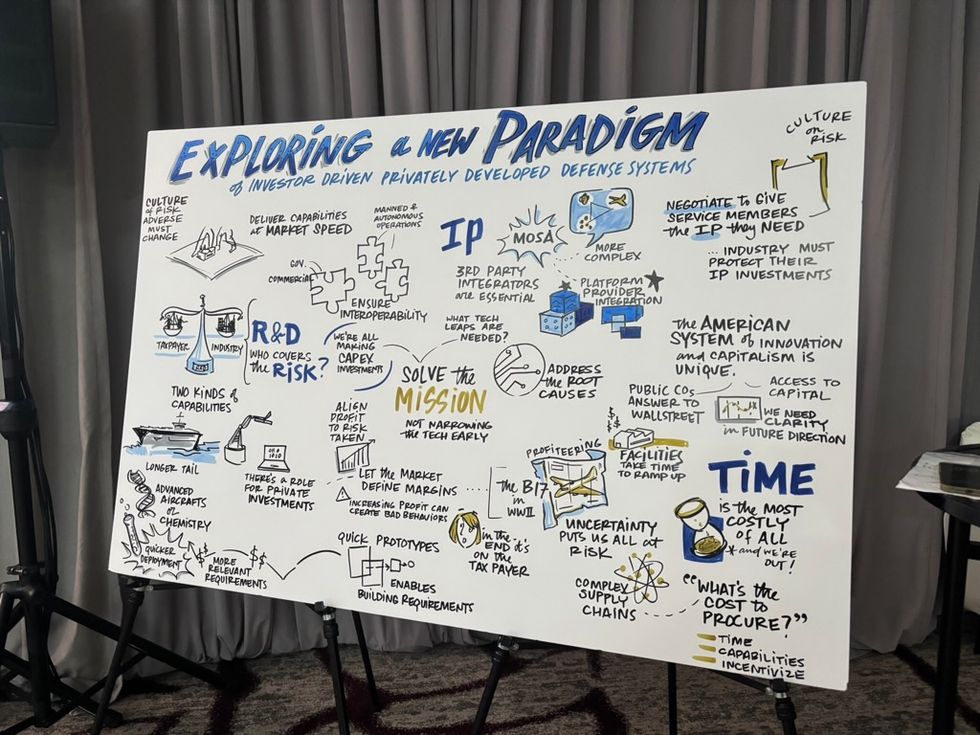

Biden’s move, Hudson reports, flies in the face of an interagency review and outside criticism that has questioned the efficacy of current counterinsurgency policies in the Sahel. According to Hudson, the Biden administration is hoping the French will follow through on reforms to what has been a dead-end strategy focused on killing top jihadists. Paraphrasing an anonymous senior administration official, Hudson writes, “The White House based its decision on the shared goal of violence-reduction and a promise from the French to put a greater focus on governance and development issues.”

Yet the French have repeatedly promised such a refocusing; the French-dominated “Coalition for the Sahel,” launched in 2020, includes governance and development as two of its four pillars, alongside counterterrorism and military training. That “coalition” has made little progress on that in the two years since.

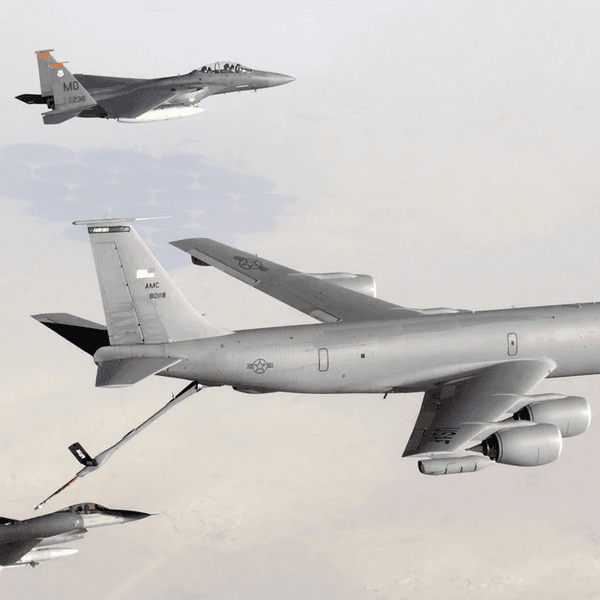

Even amid a partial French military drawdown, French policy continues to emphasize decapitation. Hudson’s article opens with an account of an October 2021 operation in Mali, conducted by French forces with the help of U.S. drone and U.S. intelligence, wherein the French kill a jihadist battalion leader. The operation, Hudson writes, was “hailed by Paris as a model for U.S.-French counterterrorism cooperation.” That the French remain so enthusiastic about killing individual jihadists — French government communications are full of descriptions of who has been “neutralized” — speaks to the myopia in French strategy.

Top-level commanders, including the leader of al-Qaida’s northwest African affiliate, have been killed, and yet the situation worsens year by year in the Sahel. The French effectively lack a strategy beyond doing more of the same, and changes to their approach have been driven more by public relations than by serious engagement with grim realities in the Sahel.

For starters, much of the violence in the region comes from state security forces and from community-based militias: in the third quarter of 2021, the UN calculated that in Mali, 54 percent of “violent incidents against civilians” were perpetrated by jihadists, but another 20 percent came from communal militias and another 15 percent from national and international security forces. Merely killing jihadists, in other words, will not rein in violence, especially in zones where conflict draws on longstanding tensions over land, now compounded by the growing salience of ethnicity.

Furthermore, for all the hope that each assassination will somehow disrupt terrorist networks, the French appear to have an overly top-down understanding of jihadism in the region. Jihadism in Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso has “social roots” that make jihadist formations more complex than just a house of cards or an “org chart” that can be pinned to the wall of a CIA analyst’s office. Removing one card, or ten, does not make the house crash down, nor does X-ing out photo after photo of long-bearded militants on the org chart. For every supposedly super-important commander or explosives expert who is killed, another takes his place.

This is the dead-end policy that Washington is supporting, a policy that mirrors failures in the U.S. approach to Afghanistan, Iraq, Yemen, Somalia, and other theaters. Consider that in Iraq, U.S. military efforts to counter Al Qaeda in Iraq (AQI) eventually reached an operational tempo of an astonishing 300 raids per month, targeting mid-level operatives — and yet top generals implied that even at that tempo, final “defeat” of the militants was impossible.

Generals suggested that U.S. forces would have had to sustain that tempo indefinitely to prevent a resurgence of AQI: “Until the political causes of the conflict are addressed, it could reemerge,” General Stanley McChrystal told one researcher. Such hopes are naïve — or, at worst, can become pretexts for open-ended deployments on other countries’ soil. The occupying power (or in the Sahel’s case, the quasi-occupying power that is France) is almost always structurally unable to address the “political causes of the conflict.”

A foreign power inevitably distorts the politics in the “host country” by propping up favorites, overlooking the abuses and corruption of the host government, and triggering anti-foreign sentiment — all dynamics that increasingly affect France in the Sahel, where its political allies are all struggling and where anti-French sentiment is on the rise. American support for French counterterrorism operations may be diplomatically expedient, but it only prolongs a dysfunctional situation where any “success” is fleeting.

(Shana Marshall)

(Shana Marshall)