On October 6, for the first time in over a decade, the Supreme Court heard arguments in a case involving a prisoner held at the U.S. detention center at Guantánamo Bay. United States v. Zubaydah presents the question: do courts have the ability to separate classified from non-classified evidence in order to allow a case to proceed? The information in question — testimony regarding suspected terrorist detainee Abu Zubaydah’s torture in black sites abroad.

Since 9/11, the U.S. government has invoked the “state secrets” privilege time and again to shield the public from knowledge about its human rights abuses and violations of law. As a result, many Americans do not know the full extent of the U.S. government’s post-9/11 history of torture and abuse — and, until recently, neither did we.

On September 11, 2001, we were three and five years old. Our father, Brian Joseph Murphy, worked in the North Tower and was killed when the first plane hit. At the time of his death, we were small children, too young to comprehend the enormity of our loss and its implications for both our family and the world. It was only much later that we learned of the events described in this case — the birth of the torture and interrogation program; the opening of the detention center at Guantánamo; the atrocities committed both at home and abroad — and how often the names of the 9/11 victims were used to justify the government’s abuse.

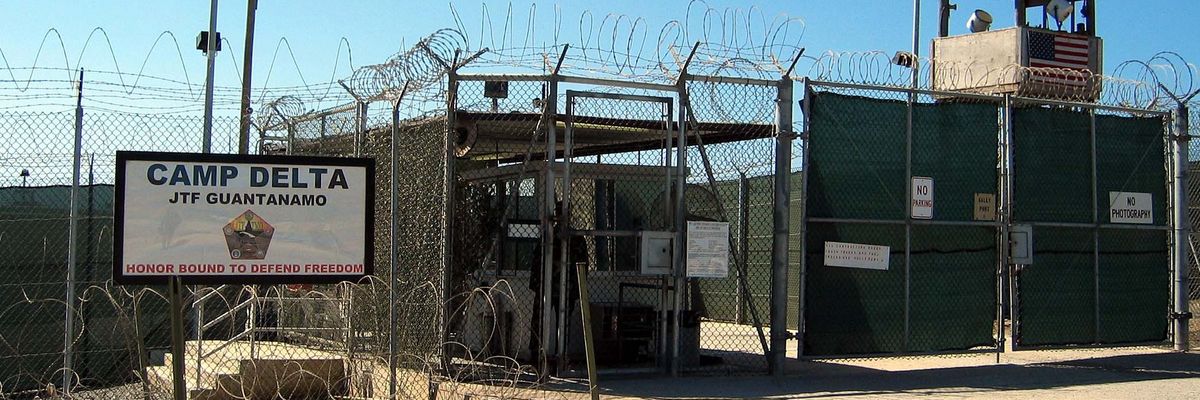

Our ignorance was not solely due to age. The government has made a concerted effort to hide its transgressions and prevent declassification of these events. The prime example is the detention center at Guantánamo. Many people, including family members of those who died on 9/11, do not know that five men accused of plotting the 9/11 attacks remain stuck in pre-trials hearings. Soon after we learned of the hearings, we decided to travel to Guantánamo to witness the proceedings ourselves, hoping to reclaim our voices as victims and see firsthand what has been done in our father’s name.

Our visit to Guantánamo in 2018 was an education in how arguments about the need to protect national security delay justice and prevent accountability for both 9/11 and its aftermath. Although we spent a full week on site, we were only permitted to watch two days of hearings — the other days were closed to all but attorneys due to discussions of “classified” information, mostly relating to the government’s Rendition, Detention, and Interrogation program.

Moreover, the hearings we were permitted to watch were hardly transparent: we sat in an observer’s room, separated from the lawyers and detainees by a soundproof Plexiglass barrier and a 40-second time delay. This protocol is deemed necessary to prevent the accidental release of information that threatens national security but in practice serves to conceal information related to torture and protect those responsible for perpetrating abuse.

After our trip to Guantánamo, we joined September 11 Families for Peaceful Tomorrows, an organization created by family members of 9/11 victims who advocate for nonviolent solutions and seek justice according to the rule of law. Last month, we joined Peaceful Tomorrows in filing its first amicus brief, on behalf of Mr. Zubaydah. We come from different perspectives, but we all agree that the secrecy, impunity, and abuse in the aftermath of 9/11 is a stain on our family members’ names — and that true justice requires true accountability for these acts.

One of the founding principles of PT is to bring those responsible for the 9/11 attacks to justice in accordance with the principles of international law. As family members, we feel particularly concerned with the impact of unchecked abuse of government secrecy in the 9/11 commissions — the issue at the heart of U.S. vs. Zubaydah. But this case is important to all Americans, as we have all been denied transparency for the injustices that have occurred over the past 20 years. Ensuring accountability is essential to prevent future atrocities and to uphold the rights that protect us all.