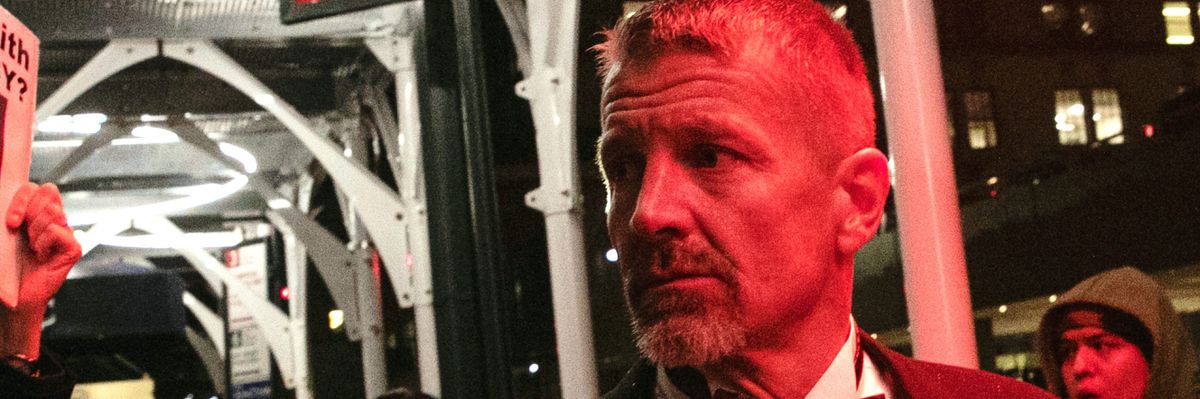

One shouldn't be surprised to find Erik Prince popping up amid the chaos of the Afghanistan withdrawal. Or, that he is trying to profit from it.

Reports today indicate that he is offering to fly stranded people from the Kabul airport on his private plane for $6,500 — for extra, he will extricate people who are cannot get to the airport.

There are few details in the Wall Street Journal article and no sense where this nugget came from, or what kind of resources he has. A former Navy Seal, Prince is the founder of Blackwater, a private security company infamous for its work on behalf of the U.S. government in the early years of the 9/11 wars. He has had his hand in several incarnations and a litany of privateering schemes since then. Most recently he was accused (but has denied) of violating the arms embargo in Libya in a plot to arm militant Gen. Khalifa Haftar so he could overthrow the transitional government there. He has also been connected to a proposal to build a private army for Ukraine against the Russians. He has been tied to the UAE, Somalia and the Chinese government. In fact, his last company Frontier Services Group, co-founded in 2014, reportedly had a contract to train Chinese police in Beijing and build a training center in Xinjiang, home to the imprisoned minority Uighurs.

At any given time, Prince has had access to more than guns. He's had planes and even ships to battle pirates on the high seas. Most of his gun-for-hire proposals never pan out, and his multi-billion-dollar salad days with the federal government seem to be behind him. Maybe even his primo access to Capitol Hill (his connections to Trump put him in the hot seat during the Russiagate period, and his sister Betsy DeVos is no longer the education secretary) is gone too.

But that doesn't mean he's out of the game. Clearly, where there is human misery and conflict, Prince is around, nibbling at the edges of opportunity. Kind of like the "Howling Man," in that Twilight Zone episode:

Wherever there was sin. Wherever there was strife. Wherever there was corruption. And persecution. There he was also. Sometimes he was only a spectator, a face in the crowd. But, always, he was there.