The chairs of the Senate’s leading foreign policy committees are calling for an investigation into President Biden’s handling of the U.S. military’s withdrawal from Afghanistan amid the Taliban’s swift (and largely expected) takeover of Kabul last weekend, and the grisly scenes of Afghans trying to flee in its wake.

Sens. Jack Reed (Armed Services), Mark Warner (Intelligence), and Robert Menendez (Foreign Affairs) are piling on the frenzy in Washington where interest in America’s longest war waned long ago, a dynamic that is seemingly playing a significant role in the collective shock at the events unfolding in Afghanistan throughout the past week.

And nowhere is that dichotomy more apparent than in these same senators’ reactions to the Washington Post’s investigation in December 2019 — dubbed the “Afghanistan Papers” — which found “that senior U.S. officials failed to tell the truth about the war in Afghanistan throughout the 18-year campaign, making rosy pronouncements they knew to be false and hiding unmistakable evidence the war had become unwinnable.”

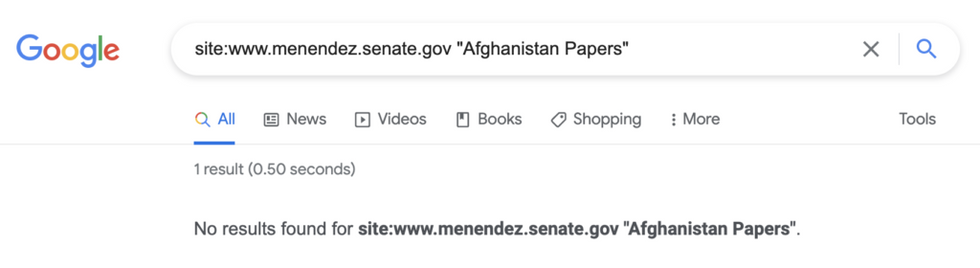

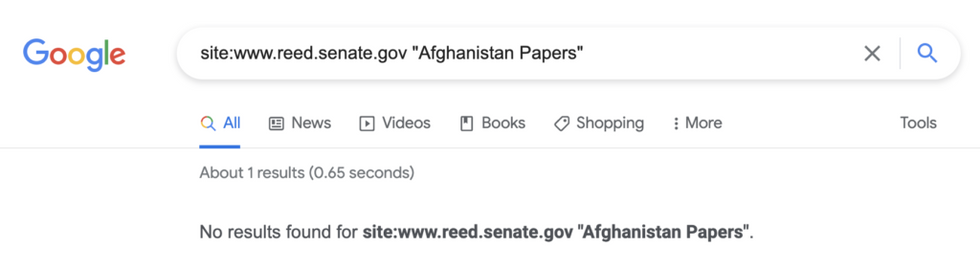

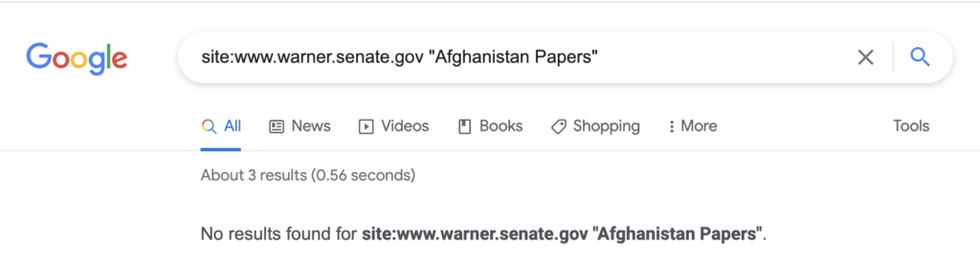

Reed, Warner, and Menendez said very little about the Post’s findings. Only Reed suggested (to a reporter) that there should be some kind of congressional investigation, but none of them made a proactive push for a hearing.* There is no record of any statement about the Afghanistan Papers on their senate websites.

This kind of selective accountability for the war in Afghanistan is indicative of how the Washington establishment is more interested in playing politics with national security while appearing to be immune to learning lessons from America’s failed militaristic foreign entanglements.

Indeed, as Sen. Bernie Sanders’ foreign policy adviser Matt Duss observed: “It is really something to watch this town attempt to absolve itself from two decades of jingoism, profiteering, barely existent oversight, and zero accountability by suddenly demanding answers about Afghanistan.”

*This conclusion is based on LexisNexis search terms: “Jack Reed OR Mark Warner OR Robert Menendez OR Bob Menendez AND Afghanistan Papers AND hearing OR investigation”