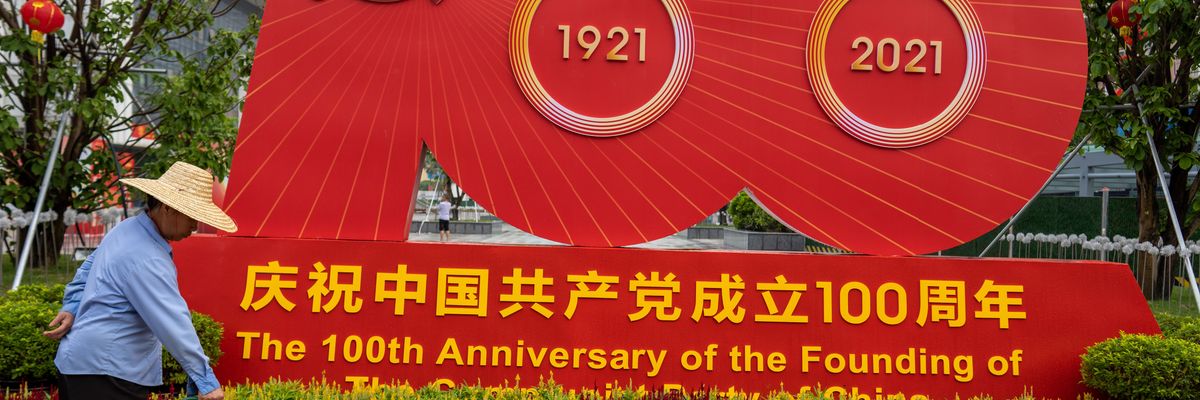

Last week, the People’s Republic of China engaged in an orgiastic celebration of the centenary of the founding of the Chinese Communist Party. Formed in secret in July 1921 by a small group of intellectuals in Shanghai — including a former schoolteacher named Mao Zedong — the CCP has grown to become a massive political entity with over 95 million members, controlling a nation of 1.4 billion people. But the path to this apparent success was by no means easy nor invariably correct.

As the U.S. struggles to deal effectively with China, it’s important to understand what the CCP is and is not, the forces that influence it most, and how it might evolve in the future. This is particularly important because the CCP is in great danger of repeating many of the mistakes it made along the way to its rise, with potentially disastrous consequences for itself and others outside China.

A successful formula for seizing power, but not for governing

Almost exterminated on more than one occasion by the rival Chinese Nationalist Party and often wracked by internal leadership disputes and purges, the CCP was eventually reformed by Mao Zedong and his closest associates into a rigidly disciplined, armed political force. In less than 15 years after Mao took control, and through a combination of nationalist and class-based appeals, this “party-army” was able to defeat its enemies and seize control of China.

However, for nearly three decades after the formation of the PRC in 1949, the CCP under Mao abused that control with disastrous results. Having no knowledge of how to promote real growth and with a naive belief in the power of revolutionary elan and organizational control, the supremely self-confident and charismatic Great Helmsman unleashed the Great Leap Forward and then the Cultural Revolution, causing the deaths of tens of millions. Adding to this domestic misery, Mao had also promoted a deep and dangerous split with the Soviet Union, supported armed revolution in many developing countries, and held a consistently hostile stance toward the West (until at least 1971), making China into a kind of international pariah.

And yet, throughout, the CCP remained in power. This was largely due to four factors that still operate in China today: 1) the lack of any viable challengers due to the CCP’s rigid control mechanisms, 2) the residual admiration that many Chinese still have toward the CCP’s ending of the “Century of Humiliation,” 3) the citizenry’s continued wide-spread fear of China lapsing back into chaos without a strong and unified center of power, and 4) the commitment to order of the CCP-controlled Chinese military, or People’s Liberation Army. Nonetheless, while ensuring national unity and recovering Chinese pride, the Mao-led CCP had not created a wealthy, strong, and respected nation, the goal of virtually all Chinese. In the mid-seventies, when Mao died, China was still a largely impoverished country, and under a serious threat of attack from Moscow.

A flexible response to failure

Enter Deng Xiaoping, a former political commissar of the PLA, twice purged by Mao. Under Deng, the CCP began its transformation from a totalitarian control and mobilization structure under Mao’s personality cult to a more pragmatic authoritarian party. This hybrid organization continued to rely upon the above four advantages that had kept it in power during tumultuous times, but added a new willingness to adopt whatever ideas, structures, and processes would promote economic growth: a policy approach described then (and today) as “socialism with Chinese characteristics.”

Under this system, ideology had become a legitimizing myth for CCP rule, not a guide to action. If China had an ideology under Deng and the reformers, it was growth, in the service of ever-greater levels of national and personal wealth, international prestige, and a seat at the table of the major powers. The CCP and its top leadership were to remain the unchallengeable guarantors of unity and order, but no longer the source of all wisdom. The logical result of this system was for the CCP to open China to productive contacts with the West and to end open ideological animosity with capitalist states.

This new formula for rule and development, utilizing CCP organizational skills and allowing local party cadres to benefit from the wealth produced by the reforms, unleashed the hugely productive aspirations for economic advancement of the Chinese people. The results have been stunning. China under the CCP today is poised to become the largest economic power in the world, with a modernizing military and growing leverage in the global arena. And membership in the CCP has become a necessary requirement for those wishing to succeed in China.

More broadly, within the Chinese population and despite its past mismanagement and cruelties, the CCP under reform has retained strong levels of popular support. This is largely due to China’s developmental success and resulting military, political, and economic power and prestige on the global scene, as well as its ability to hold a fractious and rapidly evolving nation together.

The emerging dilemma

The CCP’s very success, however, has also bred major challenges to its rule, in the form of growing levels of corruption, the spread of Western democratic and cultural ideas and values, and the likely aspirations for more freedom of at least some Chinese. Moreover, the collapse and fragmentation of the Soviet Union and Eastern European communist regimes in the 1990s, along with the rise (with U.S. backing) of anti-authoritarian colored revolutions in many developing countries added to the strong sense of insecurity that had emerged within the CCP leadership by the first decade of the new century.

This political crisis, occurring amidst the rapid growth resulting from continued reform and openness, created a dilemma for the CCP: how to sustain development while at the same time controlling the resulting fissiparous consequences of that growth? Unfortunately, despite its past flexibility and resilience, the CCP’s experience of exercising power via an armed and disciplined political force (and the population’s general desire for stability) did not provide the necessary tool kit for tackling this dilemma.

Indeed, the fear of chaos and a growing sense of threat from the West has caused the CCP under Xi Jinping to fall back on a set of failed approaches reminiscent of the Mao era. These are centered on enhanced totalitarian party control over all sectors of society and the economy, a ramped-up stress on a simplistic socialist ideology, and a growing personality cult praising Xi Jinping as the font of all wisdom. Internationally, this approach is marked by a greater level of assertiveness in advancing Chinese preferences in a host of arenas from trade and technology to sovereignty and global governance norms, often via a more muscular use of economic and military pressure.

While arguably reducing corruption and social unrest and boosting the nationalist credentials of the PRC regime within China, such an approach now threatens to stifle the creative, competitive impulses of Chinese society and unnecessarily sharpen confrontations with the West. Many Chinese intellectuals have at times offered less draconian yet still CCP-centered approaches to China’s dilemma, including a more law-based, corporatist form of rule and continued pragmatic interactions with the outside world. However, the Xi Jinping regime has spurned such alternative approaches in favor of an unstable mix of Maoist Leninism, ideology, and the market.

This attempt to have it both ways is unlikely to succeed over the long term. The forces unleashed by decades of reform and opening will eventually compel a reckoning between China’s obvious need for stable and high rates of growth and the outmoded assumptions and policy approaches of the CCP’s past. This reckoning could occur rather abruptly, creating a sharp political crisis, or more gradually, allowing for a smoother transition to less draconian rule.

The lesson for the United States

It would be incorrect for the U.S. to conclude from the above that the CCP is either on the verge of collapse due to its internal contradictions or well on its way to displacing the U.S. as the new global military and economic hegemon. It is neither, despite the fevered predictions of anti-communists and many U.S. defense analysts.

But the party’s willingness over the longer term to consider alternative patterns of rule beyond those provided by its past will depend on both its transition to a new generation of leaders more attuned to the economic and technological demands of the 21st century, and the sense of threat to both elites and the populace as a whole posed by outside powers, both militarily and economically.

The United States and other Western powers can best facilitate China’s transition to a more diverse and law-based form of rule, not by intensifying pressures on the CCP and PRC regime as a whole, but by a) improving the attractiveness of their own polities and societies; b) engaging with as wide a variety of Chinese as possible in the pursuit of common development goals and the handling of common threats, such as climate change and pandemics; and c) working with other countries to reduce the future ability and perceived need of Chinese leaders to opt for dominance over a more cooperative, multipolar order.

Unfortunately, the U.S. and many other Western countries are not pursuing this path, favoring instead “severe” competition and deterrence, reduced contact with Chinese elites, and ideological, zero-sum assessments of the nature of the challenge China poses to the outside world. This will reinforce domestic support for more draconian CCP strategies of rule, without creating the space necessary for China’s more pluralistic social and economic forces to exercise influence. It will also deepen a more aggressive and confrontational posture toward the West.

The United States must understand that the CCP is to a great extent a product of China’s historical need for order, development, and international prestige. It is neither a hostile force opposed to Chinese society nor an adequate reflection of the growing diversity of that society in the 21st century. It will need to adapt further to survive in the face of accelerating change. If the next generation of Chinese leaders recognizes the deep error of the CCP’s reflexive and wrong-headed return to past norms and is able to engage with a more receptive West in mutually productive ways, China might eventually make a peaceful transition to a regime that is able to better coexist with the West.

Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org Screengrab via niacouncil.org

Screengrab via niacouncil.org