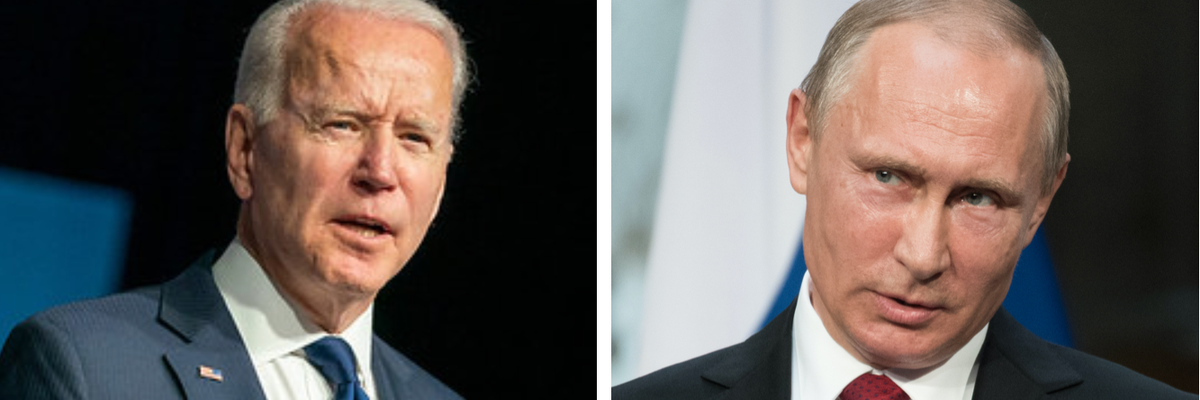

The Biden-Putin summit marks the recovery of something that should never have been thrown away in the first place: the restoration of normal diplomatic ties, the basic mutual courtesy required of leaders of serious countries, and the re-opening of negotiations in areas of vital national and global concern.

For transcripts of the two leaders' press conferences after the summit, see here and here.

In the words of Fyodor Lukyanov of the Russian Council on Foreign and Defense Policy, “In general, the talks in Geneva left a positive impression because they resemble classic summit meetings” – that is to say, summit meetings of the Cold War.

The fact that U.S.-Soviet relations during the Cold War is widely seen in a better light in comparison to today’s affairs is an index of the genuinely bad trajectory of this relationship, but also the hysteria with which it has been addressed by Western policy elites and especially by much of the Western media — a hysteria very much in evidence in their coverage of the summit.

In concrete terms, the results of the summit represent two main opportunities, and two missed opportunities. The most hopeful opportunity lies in the area of nuclear arms control. The Bush administration’s withdrawal from the Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2001 initiated a reciprocal series of actions that destroyed important parts of the US-Russian nuclear architecture. However, theU.S. and Russian decision to extend the new START Treaty until at least 2026 leaves the most important pillar of that architecture standing, and the Geneva talks open the way for negotiations to restore other parts.

In a minimally sensible world, nuclear arms reductions by the United States and Russia should be a simple matter. Both sides have far more missiles, at far greater cost, than they conceivably need. China has demonstrated that a nuclear force a fraction the size of those of the United States and Russia presents an entirely credible nuclear deterrent. For all practical purposes, the ability to destroy New York, Los Angeles and 20 other main cities is just as good (or bad) as the ability to annihilate America altogether.

The other main area where the summit opened the way for talks leading to the possibility of at least a long-term agreement is in the area of cyber security. This is a much more complicated area than nuclear arms control, partly because it is a new field where no Cold War models for agreement exist. Even more importantly, the nature of cyberspace means that there is a blurring of the lines between different areas of state activity that in the past could to some extent be kept separate.

Thus as previously argued in Responsible Statecraft critical to any negotiation for a cybersecurity treaty must be a clear distinction between cyber sabotage and cyber espionage. The blurring of this line is largely due to the intellectually and morally shoddy coverage of this issue by many American journalists and politicians, with their repeated description of Russian espionage activities as “attacks” on the United States. The Biden administration’s eschewal of the phrase “cyberwarfare” with regard to Russian actions is a helpful move in this regard.

It is also true however that to a far greater degree than in other areas, in cyberspace espionage can very easily form the basis for sabotage. The second area where lines have become blurred is between the kind of public propaganda engaged in by all states, and covert attempts at disinformation, the opportunities for which have been vastly increased by the internet.

The Western media has presented these issues almost entirely in terms of Russian attacks on the United States. Very occasionally though, through honesty or carelessness, a glimpse of another aspect of reality is allowed to creep in. Thus as the Financial Times wrote this week,

“Russia has for years sought to lay down some form of global peace treaty for cyberspace, but the US has been wary of entering any form of talks that presuppose both sides are equal, or bear equal responsibility for past cybercrimes.”

Given the US intelligence services’ record of cyber-attacks, cyber-espionage and “black propaganda” operations, this is simply not a morally or practically viable position from which Washington can begin talks on this issue, or expect the Russian state to acknowledge (even behind closed doors) its own practice of disinformation and links to cyber-crime.

The failure of the U.S. media to raise the issue of America’s past actions is of a piece with its overwhelming failure to critique Biden’s amazing statement after the summit: “How would it be if the United States were viewed by the rest of the world as interfering with the elections directly of other countries and everybody knew it? What would it be like if we engaged in activities that he's engaged in?”

Even Russians deeply opposed to the Putin administration see such statements as hypocritical almost beyond belief — as indeed do Latin Americans with any historical memory.

Two other areas were mentioned by the two leaders, but an important opportunity was missed to begin serious talks. One of these is Afghanistan. Both Biden and Putin mentioned a common U.S. and Russian interest in combating Afghan terrorism, but the common interest and basis for cooperation should go much further. Following the U.S. military withdrawal, it is only through a consensus among Russia and the other major powers of Afghanistan’s region that there can be any hope of maintaining basic stability and preventing a plunge into more dreadful civil war. Washington needs to work intensively with Moscow to build such a consensus. Otherwise, long term U.S. strategy is likely to consist of absenting itself from the Afghan political process and civil war while playing terrorist whack-a-mole with drones and targeted assassinations. This would be a betrayal of all the promises made by Washington to the Afghan people over the past 20 years.

Finally, when it comes to Ukraine, both presidents repeated their continued commitment to the Minsk II agreement as the basis for a peace settlement in the Donbas. However, there was no signal at all from the U.S. side of any desire actually to seek the implementation of that agreement or bring influence to bear on the government in Kiev to persuade it to end its obstruction of the agreement.

On the other hand, Biden avoided a new crisis with Russia (and perhaps a new war in Ukraine) by adroitly dodging a maneuver by Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky to trap him into promising Ukraine an early NATO Membership Action Plan. It seems that on Ukraine, the Biden administration has decided simply to kick the can down the road indefinitely. We must all hope that the can does not turn out to be a grenade and eventually explode in our faces.