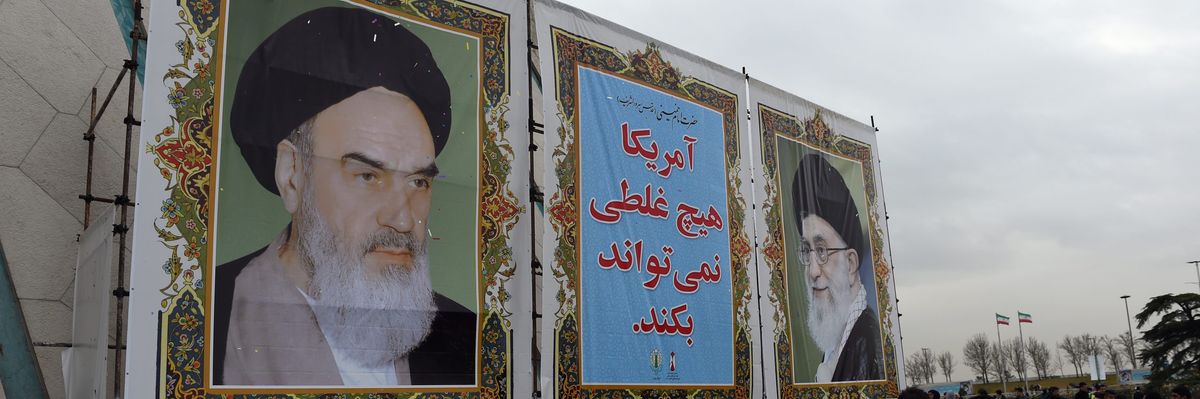

Donald Trump may no longer be president but he looms large over Iran’s presidential elections. He has proved Iran’s hardliners right for once: the United States cannot be trusted. And the consequences of his policies are now shaping Iran’s increasingly farcical elections.

Undermining America’s credibility by pulling out of the 2015 Iran nuclear agreement predictably strengthened the Iranian hardliners’ hand while giving a near death-blow to those within the Iranian power elite that favor an opening to the United States. Combined with systemic corruption and the COVID-19 pandemic, the outgoing Rouhani government and its supporters have been severely undermined by Trump’s betrayal of the nuclear agreement to the point that some hardliners, who long have entertained the idea of doing away with elections altogether, have been emboldened to manipulate the electoral process in ways that even shocked their fellow conservatives.

The Guardian Council — the undemocratic body tasked with vetting candidates — stunned the country by rejecting longtime regime insiders such as Ali Larijani, the former Speaker of the Parliament and an adviser to the country’s Supreme Leader, while only approving two non-conservatives: Mohsen Mehralizadeh, an uncharismatic former Vice President with limited name recognition, and technocrat Abdolnaser Hemmati, the former head of Iran’s Central Bank.

Centrists and reformists weren't the only ones expressing shock and dismay. Larijani’s brother, Sadegh Larijani, took to Twitter to accuse unnamed security services of interfering with the work of the Guardian Council, adding that he’s “never found [the Council’s] decisions so indefensible.” Sadegh Larijani’s critique was stinging precisely because he himself sits on the Guardian Council.

Other conservatives agreed. The editor of the hardline Tasnim news agency, Kian Abdollahi, tweeted that even many hardliners are unsatisfied with the candidate list. Three Basij centers at important Iranian universities warned that the narrowness of the approved candidates list would cause the next president to lack popular legitimacy.

The unprecedented manipulation all seems geared towards handing the presidency to hardline cleric Ebrahim Raisi in order to all but secure him as the next Supreme Leader of Iran once Ayatollah Ali Khamenei passes. The high stakes may explain why hardliners have been willing to go further than in previous elections in terms of manipulating the elections.

But it doesn’t explain their perception — and possibly the reality — that they can get away with this transparent fraud.

That’s where Trump comes in. His maximum pressure has had a devastating effect on the economy, but not the priorities and policies of the Iranian state. The pressure campaign significantly reduced Iran’s primary source of hard currencies, oil, and shrunk the economy by 12 percent in 2020. The rial has dropped precipitously in value, both due to the sanctions but also as an effect of the lack of confidence and hope within the business community that there is a light at the end of the tunnel.

Massive sanctions of this kind are in effect a form of warfare against society that hit the Iranian middle class — the core constituency favoring greater political openness and improved relations with the West — the hardest. Using Trump’s own vocabulary, it’s been nothing less than a carnage. The number of poor Iranians increased 22 million to 32 million in the first two years of maximum pressure while the middle class shrunk from 45 percent to 30 percent of the population.

According to Hadi Kahalzadeh: “Trump’s maximum pressure campaign altered the social class structure of the country by moving a significant portion of the middle class to the poverty level. The result has been to stigmatize the idea of engagement with the West as a solution to Iran’s economic woes.” Indeed, while 13 out of 14 top private road construction companies declared bankruptcy during the first two years of maximum pressure, the Revolutionary Guard-affiliated construction company Khatam‑al Anbiya doubled its projects during this same period.

While clearly having benefited from Trump’s sanctions, the hardliners and the Revolutionary Guards publicly blame all of Iran’s economic ills on the Rouhani government. This has been quite visible during the election debates these past two weeks as the hardline candidates — much like the Iranian opposition in exile — pin the blame for Iran’s economic woes almost exclusively on Rouhani while giving Trump a pass.

Of course, there is little to suggest that Iran’s hardliners would not have tried to manipulate the elections even if Trump never had pulled out of the nuclear deal. Indeed, the high stakes — setting the stage for a Khamenei-Raisi succession — and past pattern of fraud, makes attempts at cheating very likely, if not a certainty.

But trying and succeeding are two different things. The former is intrinsic to the hardliners. The latter is dependent on a whole set of external factors, of which U.S. policy towards Iran is a critical one. Trump’s contribution through maximum pressure has been to tilt the political balance heavily in favor of the hardliners by weakening and discrediting the centrist and reformists to the point that they may now succeed in doing what they earlier only could have dreamt of.

Still, Iranian elections are full of surprises. Hardline attempts at manipulating the elections have failed in the past. The rejection of former President Hashemi Rafsanjani in 2013 initially caused an uproar and similar election apathy among the population only for voters to rapidly line up behind Hassan Rouhani only a few days before election day. Rouhani went from single-digits in the polls a week before the elections to win a majority of the votes with a turnout of 74 percent.

Several factors contributed to Rouhani’s remarkable turn-around. But two essential ones were a sense among the population that he was the most viable anti-establishment candidate and that a vote for him would be a strong signal of disapproval to the establishment headed by Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. Secondly, credible voices such as Rafsanjani and former President Mohammad Khatami pleaded with the population not to boycott the elections.

Today, there are embryonic signs that former Central Bank head Abdolnaser Hemmati may emerge as the uniter of the anti-establishment vote. But a key difference from 2013 is that the calls for boycotting the elections are much louder and even coming from figures within the regime, while few influential voices have embarked on compelling anti-boycott campaigns.

Despite their efforts, the hardliners may still fail and the presidency may not be captured by them. But if they succeed with this open fraud, the United States and the European Union should carefully study their own role in Iran’s big leap towards greater authoritarianism — and resist doubling down on the very policy that helped bring about this hardline take-over in the first place.