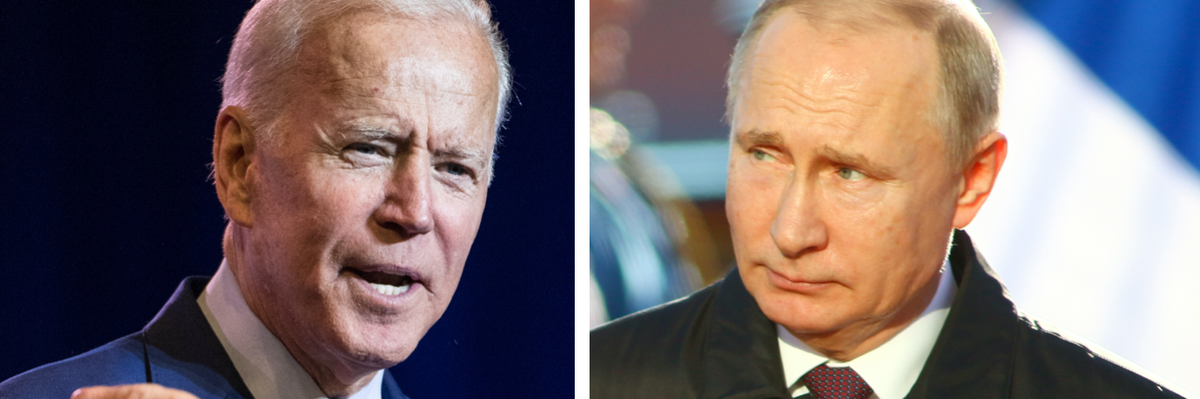

At the summit between presidents Biden and Putin in Moscow, the conflict in the Donbas region of Ukraine and the dispute over Crimea will be high on the agenda and will interfere greatly with the discussion of other issues.

However, as I lay out in a brand new Quincy Institute paper, “Ending the Threat of War in Ukraine: A Negotiated Solution to the Donbas Conflict and the Crimean Dispute,” as long as the United States fails to engage in a genuine search for compromise over the Donbas, and in effect gives backing to completely unrealistic and irrational Ukrainian positions, this and all future U.S.-Russian discussions on the question will be futile.

The existing U.S. approach is a classic example of a zombie policy: a dead policy that walks around pretending to be alive because the Washington establishment cannot summon up the will and courage to bury it. For there is no chance whatsoever of this policy ending the conflict, helping Ukraine to recover its lost territories, or enabling Ukraine to join NATO.

But as every moviegoer knows, zombies can be extremely dangerous, and the Donbas conflict represents by far the greatest danger of a new war in Europe, and of a new crisis in relations between the United States and Russia. The Biden administration does not wish to escalate tensions with Russia, but so long as these disputes remain unsolved, the United States will be hostage to developments on the ground that could drag it into new and perilous crises.

A war could end only in Ukrainian military defeat, and perhaps in the loss of much larger territories. The United States, which has declared “unwavering” support for Ukraine in the dispute would be faced with the choice of either going to war with Russia (an unthinkable proposition with disastrous consequences for the United States and its citizens), or leaving Ukraine to its fate and suffering a dramatic loss of international credibility.

The threat of war with Ukraine will not shift Russian policy. The United States did not fight for Ukraine in 2014, or for Georgia in 2008. And as of 2021 America has only some 26,000 ground troops in Europe — and most certainly could not rely on the participation of its European allies in a war with Russia. Russia has more than ten times that number that it could deploy quickly to fight in Ukraine. To prepare seriously for war with Russia would require a colossal redeployment of U.S. forces to Europe — so colossal that placing military checks on the expansion of Chinese power would have to be abandoned.

Over the past seven years, U.S. and EU sanctions against Russia have also not worked in the slightest to make Russia accept Ukrainian terms over the Donbas and Crimean disputes. There can be no rational basis for thinking that they will work in future, not least because the strength of Russian nationalism means that no conceivable future change of regime in Moscow will change Russia’s basic approach.

Ukrainian economic pressure, like the blockade of the Donbas and the cut-off of water to Crimea, may push Russia towards compromise — but only if Ukraine and the United States are also prepared to compromise. If not, there is an equal risk that Russia will eventually respond to this pressure with force of arms. It is therefore emphatically in the interest of the United States, as well as Europe and Ukraine itself, to find a peaceful political solution to this conflict.

There is, however, no chance that such a solution can be based on the position of Ukrainian governments since 2015 — that full Ukrainian control be re-established, the separatist forces disarmed, and Russian forces withdrawn before the granting of autonomy, and that any autonomy legislated by the Ukrainian parliament will in any case be only provisional.

A glance at the history of other peace processes around the world should demonstrate the senselessness of this position. It demands in effect that the separatists and their Russian backers surrender in advance in return for only temporary and unconfirmed Ukrainian concessions. No separatist force in the world would make peace on these terms. Only the defeat of the Russian army could bring about this outcome, and the defeat of the Russian army could only be accompanied by a new world war. Kiev and Moscow must therefore find a compromise.

The dictates of reality, the wishes of the people of the region, and modern international tradition all point in the same direction: a settlement derived from the principles agreed (but never implemented) in 2015 by the “Minsk II” group of France, Germany, Russia and Ukraine, and endorsed by the United Nations Security Council . “Minsk II” calls for extensive autonomy for the Donbas within Ukraine, guaranteed by international treaty and the presence of an international peacekeeping force.

Above all, this solution would correspond to something that the discourse on this issue in Washington too often completely forgets, despite America’s sense of democratic mission: namely, the wishes of the local people themselves. Both before and since the outbreak of war, pluralities in local opinion polls repeatedly supported autonomy for the region within Ukraine. Only minorities have wanted either union with Russia or centralized rule from Kiev.

In Crimea, opinion polls before 2014 showed majorities for independence, and it seems probable that if a new referendum were held under international supervision, then as with the internationally unrecognized Russian-held plebiscite of 2014, it would result in a vote for union with Russia.

The Minsk II agreement was also endorsed by the Obama administration, but since then no U.S. administration has done anything serious to bring it into effect. But it is above all, the stance taken by Ukrainian governments that has made implementation of the agreement possible, and there is therefore no possibility of progress without real pressure by the United States on Ukraine as well as on Russia.

Accordingly, the United States should actively help to broker a solution along the following lines:

— The restoration of Ukrainian sovereignty over the Donbas region (namely the provinces of Donetsk and Lugansk), including the return of Ukrainian customs and border guards.

— Full autonomy for the Donbas region within Ukraine, including control over the local police.

— Complete demilitarization of the region, including the disarmament and demobilization of the pro-Russian militias, the withdrawal of all Russian “volunteer” fighters, and the exclusion of all but token Ukrainian armed forces.

This settlement should be endorsed by a UN Security Council resolution, with a neutral UN peacekeeping force stationed in the Donbas to guarantee autonomy and prevent a new conflict.

The issue of Crimea is different and separate from that of the Donbas, since Crimea has been annexed by Russia and no armed conflict has occurred there. However, Crimea does constitute another major stumbling block in U.S.-Russian relations, hindering agreement on other issues and carrying the potential for future crises. The resolution of this issue is therefore desirable, and it should be accomplished by a new local referendum held under UN monitoring and supervision, and linked to a diplomatic compromise whereby Russia recognizes the independence of Kosovo.

Those critics who declare that such an approach is impossible for the Biden administration have a duty to propose an alternative approach that stands some chance of ever actually succeeding. If they cannot, then they are trying to commit the United States to one side in a frozen conflict that will be in perpetual danger of exploding again, with permanent damage to wider U.S. interests in the world. An American statesman — as opposed to a politician — in these circumstances should have no hesitation in following the advice of former Defense Secretary Robert A. Lovett: “Forget the cheese – let’s get out of the trap.”