President-elect Joe Biden will soon finish selecting the men and women who will staff his incoming administration. The first announcements comprise the core of his foreign policy team, including the nomination of his longtime confidant Antony Blinken to be the next Secretary of State.

Blinken, as both a former deputy national security adviser and deputy secretary of state under Barack Obama, is highly qualified for the position. But as the American Conservative’s Daniel Larison explained on this website, experience does not equal judgement. For over two decades Blinken has been a proponent of escalating U.S. involvement overseas, both in flexing soft power and using military force.

Antony Blinken is more likely to recommend sending the U.S. Army to Damascus than he is to have his own “Road to Damascus” moment from which he emerges as an apostle of realism and restraint. But he should be aware that there is an alternative, one that befits an older, more traditionally American ethos.

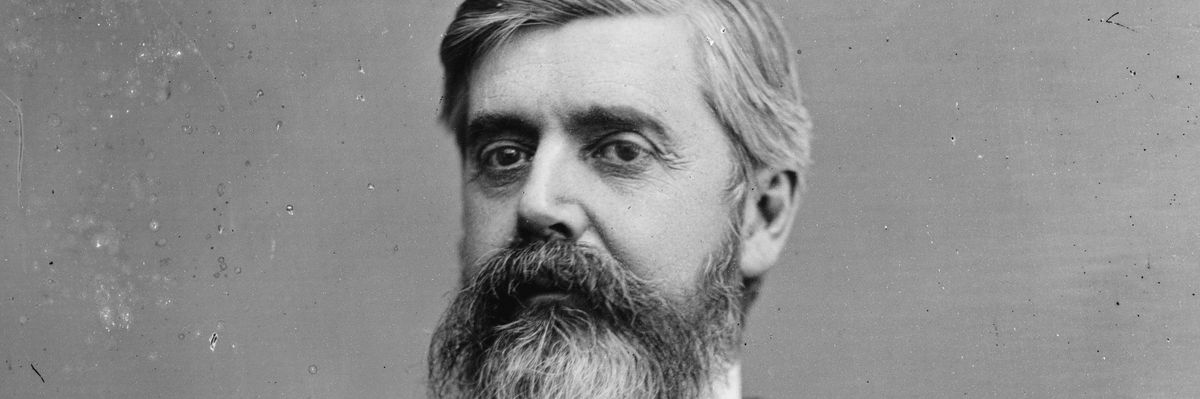

Looking back to the nineteenth century, we find a secretary of state whom the writer Bill Kauffman labeled “quite possibly the most anti-imperialist diplomat in the history of the republic.” No, not the oft-quoted John Quincy Adams — but the unappreciated Walter Q. Gresham.

Spending most of his career as a judge in his native Indiana, Gresham also served briefly in the cabinet of President Chester Arthur, first as postmaster general and then secretary of the treasury. Despite being a lifelong Republican, by the 1890s he felt increasingly out of step with the party’s devotion to prohibitively high protective tariffs. A lifelong free-trader, Gresham broke ranks and endorsed Democrat Grover Cleveland in his successful return to the White House.

Cleveland rewarded this pivotal endorsement by offering Gresham the cabinet’s most preeminent office: secretary of state.

Reactions were hostile, with Democrats displeased at seeing the job given to a party newcomer, while Republicans forever resented the turncoat. “Possibly no other cabinet appointment ever caused so much comment and criticism as that of Judge Gresham to the office of Secretary of State,” wrote historian Martha Alice Tyner.

And then there was the question of experience; unlike Blinken, Gresham had no background in foreign affairs. Woodrow Wilson, then a Professor at Princeton, had low expectations and surmised that Gresham would be “a novice in adjusting the foreign relations of the country.” Dismissing the judge’s skillset as befitting a lower office, Wilson jabbed that it was a pity “to lose so fine a Secretary of the Interior.”

Gresham’s ability would be tested early. In January 1893, a group of American businessmen organized a coup d’état in Hawaii, overthrowing the indigenous monarchy. The plotters’ efforts were buttressed by a company of U.S. Marines under orders from John W. Foster’s State Department. It was in effect the first regime change operation performed under the auspices of the U.S. government — and it would be Foster’s grandsons, John and Allen Dulles, who would organize more coups in Iran and Guatemala in the 1950s.

Hawaii’s new provisional government — headed by a “Committee of Safety” composed mostly of U.S. citizens — immediately sent a proposal of annexation to Washington. With less than a month left in his term, President Benjamin Harrison signed the proposal and delivered it to the Senate, which did not act before Cleveland’s inauguration.

The first act of Cleveland’s presidency was to rescind the treaty, and for Gresham to repair the international damage caused by Foster. “Can the United States consistently insist that other nations shall respect the independence of Hawaii while not respecting it themselves?” asked Gresham. “Our government was the first to recognize the independence of the islands, it should be the last to acquire sovereignty over them, by force and fraud.”

Adhering to the traditional American opinion that “a free government cannot pursue an imperial policy,” Gresham believed that if acquired, Washington could only govern Hawaii as “Rome governed her provinces, by despotic rule.”

To “satisfy the demands of justice,” Gresham attempted to negotiate the restoration of the Hawaiian monarchy, but arbitration broke down when Queen Liliuokalani — then under house arrest — refused to grant amnesty to the American plotters. The provisional government remained in place until Hawaii’s annexation in 1898 under President William McKinley.

Gresham rejected the idea that Hawaii — an archipelago located 2,000 miles from the Californian coastline and closer in distance to Tokyo than Washington, DC — could be of any material interest to a continental power like the United States. Instead, he discerned his own explanation for the attempted annexation. In a private letter to a senator, the secretary of state wrote that “the armed power of this country [had been used] to destroy an innocent and helpless people in order that New England corporations (forty of them) might get possession of their property, own their sugar plantations, and wring out of the pockets of the American people a bounty...”

While Gresham understood pernicious corporate influence, Blinken is a biproduct of corporate power. In 2018 he cofounded the consulting firm WestExec Advisors, whose purpose was to advance the interests and profit margins of defense contractors. Is that preferential treatment expected to end when Blinken arrives at Foggy Bottom?

The Indianapolis Journal described Gresham as “blunt [and] aggressive,” and his counsel to men like Antony Blinken, who would exploit American strength to perform gratuitous meddling overseas, is pertinent. He said, “Every nation, and especially every strong nation, must sometimes be conscious of an impulse to rush into difficulties that do not concern it, except in a highly imaginary way. To restrain the indulgence of such a propensity is not only the part of wisdom, but a duty we owe to the world as an example of the strength, the moderation, and the beneficence of popular government.”

Gresham believed that “the only safeguard against all the evils of interference in affairs that do not specially concern us is to abstain from such interference altogether.” If Americans did not “stay home and attend to their own business,” then “they would go to hell as fast as possible.”

And can’t our foreign policy be described as a kind of hell? That’s what it must feel like for the Yemeni, Iranian, and Venezuelan families who suffer from hunger and sickness as an effect from U.S. sanctions. Or for the people of Iraq, who have endured almost continual American bombardment for 30 years.

Walter Q. Gresham died from pneumonia halfway through his term at the age of 63. Judging his record, The Nation magazine wrote, “Mr. Gresham has been a great success and has made American honor, capacity, and courtesy mean more in the eyes of the world than they had meant for many a day.”

Honor, capacity, and courtesy. Are those not qualities American foreign policy is in desperate need of? Honoring the sovereignty of other nations and their right to construct their own political and social systems. Understanding the capacity of American power, and not overextending our commitments beyond our capability. And replacing belligerence and poison pill preconditions with diplomatic courtesy and outreach.

When Antony Blinken fails at enacting a foreign policy that places the needs of the republic before those of the empire, it will not be for lack of precedent.