On July 14, 2015, the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action was finalized in Vienna between Iran, the five permanent U.N. Security Council members plus Germany, and the European Union as the arbiter of the negotiations. Iran’s foreign minister Javad Zarif tweeted about the deal being “not a ceiling but a solid foundation” to build on. Three months earlier — after the political agreement of the nuclear talks was reached in Lausanne — Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei had characterized this process as an “experience” which “if the opposite side gives up its misconduct” can be continued on “other issues.”

This “experience” could not have ended up worse. Seeing a deal fall apart despite having fully abided by it makes it almost impossible in Iran’s domestic scene to make the case for any renewed engagement. Only less than two weeks ago, Zarif had to defend his diplomatic conduit in an extremely heated parliamentary session.

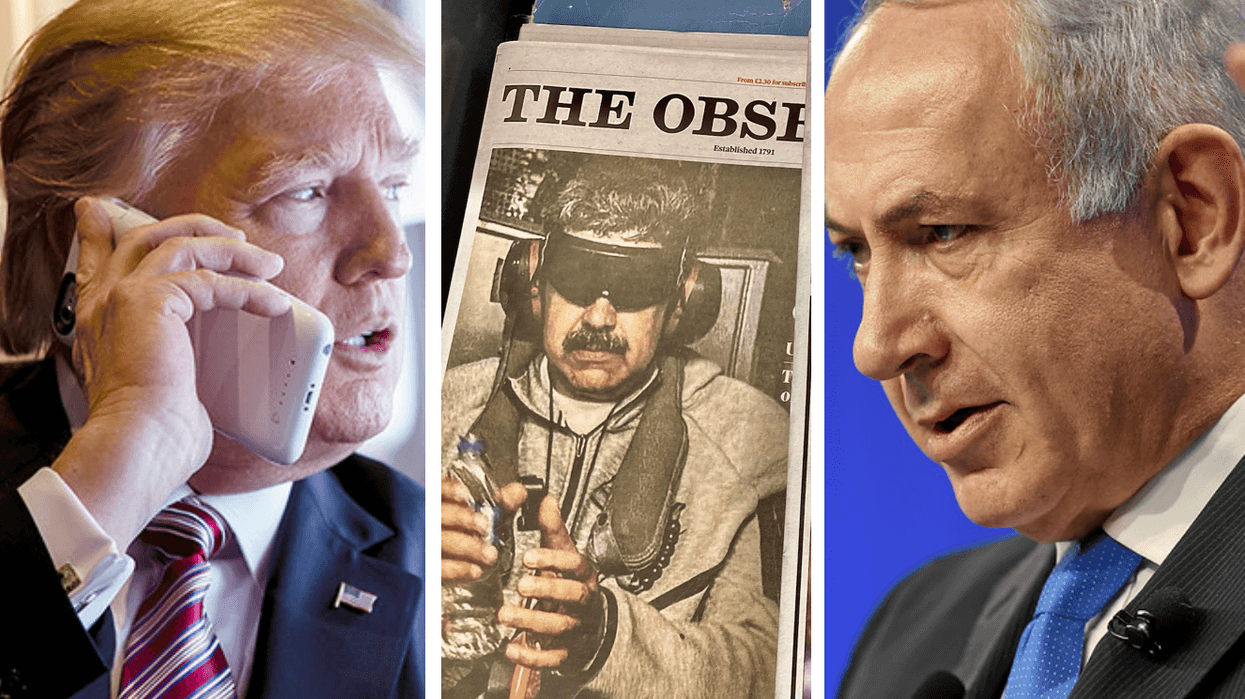

Since May 2019, a year after President Donald Trump withdrew the United States from the JCPOA, and with lost hopes about Europe being capable of safeguarding the deal, Iran has started to gradually reduce its nuclear commitments, of which only the International Atomic Energy Agency inspections remain in place.

Fatigue instead of festivity

As a consequence, instead of a festive mood about the anniversary of the most comprehensive nuclear non-proliferation agreement in history, a “JCPOA fatigue” can be sensed on all sides. Opponents of the deal seem to have successfully “out-zealed” its proponents, by ensuring that a positive political momentum around a primarily technical security agreement could never flourish.

Things can be expected to get even worse with the current U.S. effort not to allow the arms embargo on Iran to be lifted in October this year, as the JCPOA postulates. The U.S. is furthermore warning that it will make the case about Iranian breaches of the deal in the U.N. Security Council to trigger a ‘snap-back’ of all U.N. sanctions on Iran — even if that requires the U.S. to claim itself still a participant to the JCPOA.

In spite of the fatigue, it is now or never to push back against this approach. The consequences of a JCPOA collapse and the outright assault on the diplomacy behind it are multilayered, because this agreement has been as much about nuclear non-proliferation and arms control in the Middle East as it has been about Iran.

Implications on engagement with Iran

The JCPOA showed that the compartmentalization of problematic issues processed through multilateral diplomacy produces actual results — results that, as the above-mentioned quotes by Foreign Minister Zarif and Supreme Leader Khamenei show, are then supposed to be built on.

It is not as if the alternative to diplomacy, being sanctions and pressure, had not been tested before. In fact, the years 2013 to 2016 were an exception to decades of sanctions and coercive policies on Iran. One may wonder why “maximum pressure” would deliver now what three and a half decades of the very same recipe had not.

The European inability to resist U.S. secondary sanctions during the maximum pressure campaign made Iran realize that normalization of economic relations with Europe is not possible without having the U.S. on board. It should therefore be no surprise that talk about a strategic 25-years partnership agreement between Iran and China is currently all over the place. In its quest to survive economically, and with the experience of Europe bowing to U.S. secondary sanctions, Tehran may very well have shifted away from Europe to China for good.

Furthermore, it has become clear for Iran that its conflict with the U.S. can only be set aside in direct Tehran-Washington talks. On neither side are Europeans viewed as respected mediators any longer.

In such a context, any possible future Iran-U.S. talks, as distant as they currently may seem, bear the potential of creating a deeper rift into transatlantic relations, since Iranian-American arrangements in security affairs for the Middle East, an immediate neighborhood of Europe, could be developed without European stakes being taken into consideration.

Consider Iran and the U.S. agreeing on a smooth exit of U.S. troops from Iraq, Syria and Afghanistan — something the Islamic Republic has aspired to since its foundation, and Trump never gets tired of emphasizing in his presidential campaign. All three contexts are of high importance to Europe — and yet, there would be no leverage left for it to shape the outcome.

Such a transactional tradeoff would mainly focus on reducing the costs of ongoing tensions between Iran and the U.S. Whether or not such arrangements would bring enduring peace and stability to either country remains questionable. For that, a comprehensive multilateral approach would be necessary, one that includes a much broader array of regional and extra-regional stakeholders in the Middle East.

Implications on non-proliferation and arms control in the Middle East

The JCPOA was designed not as a traditional nuclear disarmament or arms control agreement, as this was not about two sides adopting symmetric measures, but as one that focused only on Iran’s nuclear program. It was asymmetric in essence because it demanded concrete technical nuclear-related obligations from Iran’s side in exchange for legal or sanctions related obligations from the other side. Should this model of “non-proliferation diplomacy” fall apart, future approaches regarding nuclear proliferation and arms control in the region will need to be addressed regionally.

In a post-JCPOA setting, Iran would no longer accept being singled out and could demand its very own security concerns in the Middle East be addressed too. These include the long-range and nuclear-armed ballistic missiles of Israel; the long-range precision-strike capabilities of Israel, Saudi-Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and the omnipresence of the US military in Iran’s immediate neighborhood.

Economic incentives in exchange for nuclear concessions will no longer be attractive for Iran, as it has proven not to work in the framework of the JCPOA. Hence, for any arms control approach to be brought forward, a more symmetric arrangement between key regional rivals such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, Israel, the UAE, and Qatar would have to be found.

There is no doubt that a long-term and comprehensive arms control agreement for the Middle East is necessary. But for it to be initiated on solid grounds, a landmark agreement such as the JCPOA would need to serve as a success story.

Iran has warned multiple times that it will leave the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty, should the arms embargo be extended beyond October this year, or should U.N. sanctions be reinstated. With Saudi Arabia and the UAE showing nuclear ambitions too, nuclear competition in a region full of conflict and deadly rivalry appear to be an all too realistic scenario.

Against this backdrop, all efforts should be channeled now into safeguarding the nuclear agreement in order to set a positive precedent for multilateral U.N. backed negotiation formats — a format which produced a solid “inspect and verify” mechanism for a context full of mistrust.

Verbally rejecting the current U.S. approach will not be enough. Europe, in particular, will have to invest more into facilitating economic relief to Iran, in a time when the country has asked for a $5 billion IMF loan in its quest to battle the COVID-19 pandemic.

Democrats in Washington, who have signaled their willingness to return to the JCPOA should Joe Biden become President in November, will need to develop very concrete signals to be sent to Tehran before and immediately after November 3.

Only then, the government of Hassan Rouhani will be in the position to buy further time at home, and do its part to safeguard an agreement that Rouhani would still like to be the major accomplishment of his presidency.