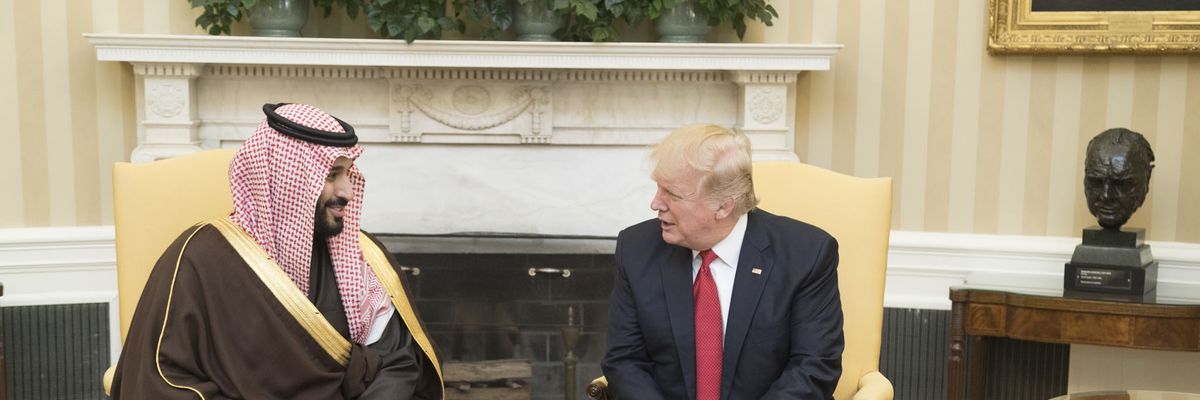

In a phone call last month with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, President Donald Trump delivered Riyadh an ultimatum: if the oil price war with Russia doesn’t stop immediately, the U.S. troops and Patriot anti-missile systems that have been deployed to the Kingdom would be preparing for a withdrawal order.

We know how the story ended. After days of high-stakes talks, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and other oil producers in the OPEC-Plus group of nations agreed to a monthly production cut of just under 10 million barrels of day, roughly 10 percent of the world’s output. Trump’s pressure on Riyadh very likely had a role in accelerating negotiations towards an agreement. But it holds an even larger lesson for the Washington foreign policy establishment: the United States needs Saudi Arabia far less than Saudi Arabia needs the United States.

U.S.-Saudi relations could use a total, unadulterated recalibration. The status-quo, where U.S. troops are sent to protect the Kingdom despite Saudi Arabia spending more money on its military — $61.9 billion — than Turkey, Iran, Israel, and Kuwait combined — $61.2 billion — is not aligned with 21st century realities. The latest reports of a U.S. military redeployment from the Kingdom, assuming it proceeds, could serve as the starting point for a re-evaluation of bilateral ties.

The old paradigm that has served as the foundation of the U.S.-Saudi relationship over the previous 75 years — security for Riyadh in exchange for reliable oil supplies for Washington — is no longer as applicable as it once was. With the U.S. public increasingly opposed to seeing U.S. troops bogged down in the Middle East and Riyadh committing a litany of brazen foreign policy errors, the 1945 understanding is as relevant today as black-and-white television.

Washington no longer needs Saudi oil to power its domestic industry or fuel economic growth back home. While the U.S. cannot completely shield itself from the global energy market, it’s also true that the U.S. today relies far less on crude from the Persian Gulf than it did in the 1950s, 1990s, or early 2000s. A rise in domestic production has roughly correlated with a 48 percent decrease in U.S. imports of Saudi oil and a 50 percent cut in total imports from the Persian Gulf over the same period of time. The domestic shale boom has removed a key point of leverage from foreign nations that have used energy as a weapon in the past.

As the oil price crash in March and April demonstrated, Saudi Arabia is now a U.S. energy rival. To expand market share, Riyadh has sought to drive U.S. producers out of business. U.S. lawmakers from energy-producing states like Texas and North Dakota understand this, which is why they were fuming when Saudi Arabia and Russia dumped crude into the market. With the market vastly oversupplied, hundreds of U.S. shale companies could be forced into bankruptcy.

The battle for energy is hardly the only dispute between Washington and Riyadh.

Ever since bin Salman ascended the Saudi hierarchy, Riyadh’s foreign policy has been a raging dumpster fire. Saudi Arabia’s war in neighboring Yemen against the Houthis, which Saudi officials confidently predicted would last only a few weeks, has become the Kingdom’s worst foreign policy debacle since its foundation.

In the five years since the war began, over 100,000 Yemeni civilians have been killed, 80 percent of the country’s population requires humanitarian assistance to survive, and 2 million children are at risk of malnutrition. The bombing from the air and fighting on the ground has put half of Yemen’s hospitals and clinics out of operation, which means the country is in even worse shape as it prepares for a looming COVID-19 pandemic. U.S. weapons systems sold to the Saudis and their UAE partners have ended up in the hands of Islamic extremist groups, some of which are tied to Al-Qaeda. Despite having no U.S. national security interest at stake in Yemen’s civil war, Washington continues to protect Riyadh at the United Nations from war crimes charges arising from the conflict.

In this bilateral relationship, Saudi Arabia has an incentive to convince the United States that Riyadh and Washington’s national security interests are in perfect harmony. Riyadh has proven quite effective in this regard. When Iran allegedly attacked Saudi oil installations in September 2019 with cruise missiles, Washington heeded Saudi requests for protection by deploying U.S. servicemembers and anti-missile batteries to the Kingdom. Today, 3,000 U.S. troops, fighter squadrons, and air-defense systems are stationed in Saudi Arabia, performing a national defense mission that the Saudi military is more than capable of performing itself.

This doesn’t mean the U.S. needs to turn its back on Saudi Arabia completely. In a world where realism and great-power politics are the engines that drive international affairs, it would be a serious mistake to write off any country that may have value to Washington in the future. Washington and Riyadh do share a few common interests where collaboration is an entirely reasonable thing to pursue. Intelligence cooperation against terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda and the Islamic State makes imminent sense for both nations — particularly for the Saudis, whose family dynasty has long been in the crosshairs of these groups. To the extent U.S. and Saudi officials can minimize their disagreements on the oil market’s supply and demand, they shouldn't hesitate to do so.

But if it’s unwise to overturn the relationship entirely, it would be even more unwise and dangerous for Washington to continue engaging with Saudi Arabia as if we still live in the 20th century. The world has changed — and U.S. foreign policy must change along with it.