As noted by Andrew Bacevich and others, the United States’ expensive national security apparatus has been conspicuously useless in efforts to combat the COVID-19 pandemic, the most serious national and global security challenge of our time.

Hobbled by secrecy and timidity, the U.S. intelligence community’s silence today represents a departure from the straightforward approach of then-Director of National Intelligence Dan Coats a year ago. He offered a clear public warning of the risk of a pandemic at the annual threat hearing of the Senate Intelligence Committee in January 2019:

"We assess that the United States and the world will remain vulnerable to the next flu pandemic or large-scale outbreak of a contagious disease that could lead to massive rates of death and disability, severely affect the world economy, strain international resources, and increase calls on the United States for support.”

This year, for the first time in recent memory, the annual threat hearing was canceled, reportedly to avoid conflict between intelligence testimony and White House messaging, and the 2020 worldwide threat statement remains classified.

The U.S. intelligence community evidently has nothing useful to say about the origins of the pandemic, its current spread or anticipated development, its likely impact on other security challenges, its effect on regional conflicts, or its long-term implications for global health. All of these topics are perfectly suited to open source intelligence collection and analysis. But the intelligence community disabled its open source portal last year. And the general public was barred even from that. The intelligence community has been reduced under the Trump Administration to recirculating reminders from the Centers for Disease Control to wash your hands and practice social distancing.

It didn't -- and doesn't -- have to be that way. In 1993, my organization, the Federation of American Scientists created an international email network called ProMED -- Program for Monitoring Emerging Diseases -- which was intended to help discover and provide early warning about new infectious diseases.

Run on a shoestring budget, the project was based on the notion that physicians, scientists, researchers, and other members of the public — not just governments — have a need for current threat assessments that can be readily shared, consumed and analyzed. The initiative quickly proved its worth, as notices on ProMED first alerted the world to the 2003 SARS outbreak. Now managed by the International Society for Infectious Diseases, ProMED was also first to bring news of the novel coronavirus in China to the West -- in a posting on Dec. 30, 2019 about chatter on the Chinese social network Weibo.

ProMED is unclassified, free, and open to subscription by anyone.

Based on the epic fail of the intelligence community to spot and alert the government and public to this pandemic, a greater focus on public intelligence should surely be one of the post COVID reforms this country undertakes as it reconfigures U.S. intelligence apparatus.

Is the military doing any better?

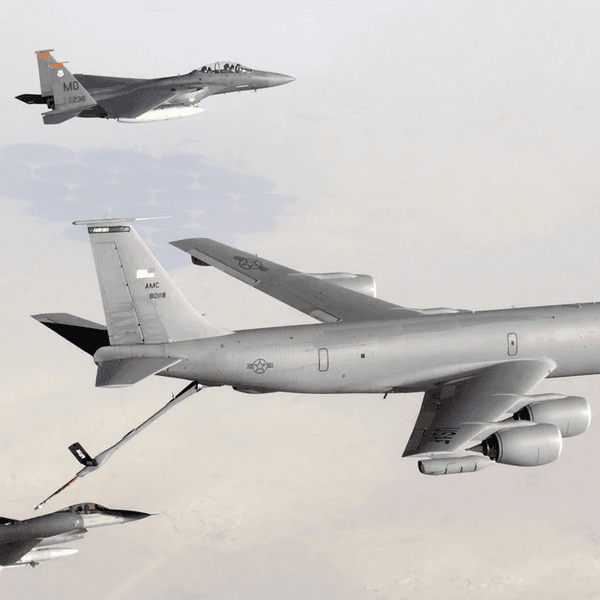

So what about the public’s $700 billion investment in the Department of Defense. How is it being used to fight this very real threat?

There is a bewildering amount of official guidance on the role of the military in circumstances such as the current pandemic. But the practical impact of that guidance, whatever it may be, is unclear. Like the proverbial war plan that cannot survive first contact with the enemy, Pentagon doctrine on infectious disease seems to have been overtaken by events.

"The mission of DOD in a pandemic is to preserve U.S. combat capabilities and readiness and to support U.S. government efforts to save lives, reduce human suffering, and slow the spread of infection," according to a 2019 Army manual.

To help accomplish that, another military manual offered a "prioritized and tiered [list of] infectious diseases [to] assist the military research community in focusing on the development of vaccine, prophylactic drugs, diagnostic capabilities, and surveillance efforts."

Pandemic influenza was among the highest priority diseases, posing a "high operational risk," but unfortunately the intended military research response appears to have lagged.

Who is in charge? Well, "USNORTHCOM [U.S. Northern Command] exercises coordinating authority for planning of DOD efforts in support of the USG response to pandemic influenza and infectious disease," says a Pentagon publication (JP 3-40) on Joint Countering Weapons of Mass Destruction.

What is NORTHCOM doing? "DoD has nearly 11,000 personnel dedicated to COVID-19 operations nation-wide, with nearly 2,500 in the New York City area," according to an April 10 news release. "DOD is providing expeditionary medical care in several states across the country."

According to military researcher William M. Arkin, "NORTHCOM is out there working furiously to carry out its many missions, implementing at least five different operations plans simultaneously.” But "Implementing might be too strong of a word," he wrote, "because even though these plans run in the hundreds of pages, most are thrown out the window almost as soon as they are taken off the shelf, useful in laying out how things should be organized but otherwise too rigid -- or fanciful -- to apply to the real world."

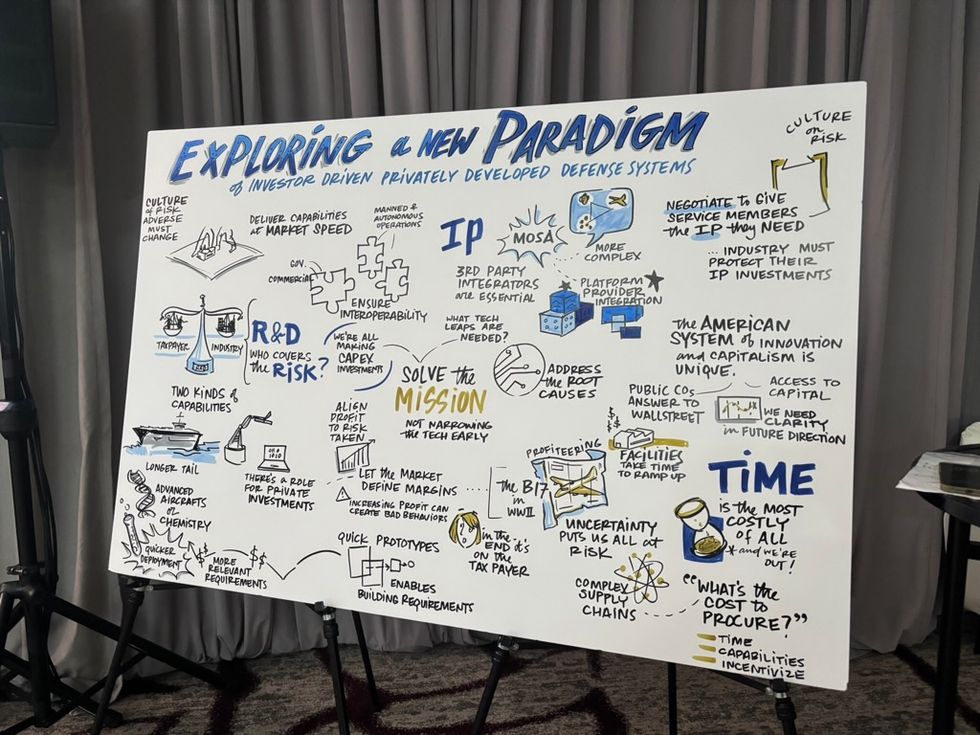

In a new piece, Arkin surveyed 19 operational military plans that in theory govern NORTHCOM activities. Most of them are not publicly available, and some are classified. "Is there any reason you can imagine that the pandemic response plan shouldn't be public? Or the plan for Defense Support of Civil Authorities?” asks Arkin.

One of the plans he turned up, a 2017 NORTHCOM draft on Pandemic Influenza and Infectious Disease Response, identified what it termed "critical vulnerabilities" including:

"Lack of communication and synchronization among partners and stakeholders, inability or unwillingness to share information / biosurveillance data, limited detection capabilities, and limited laboratory confirmatory testing."

Sounds about right.

Unfortunately, that particular plan from 2017 "seemingly never went beyond the draft stage," said Arkin.

The Pentagon’s vaunted deep bench for planning is just that. A deep bench. Not nearly adequate in this critical case.

This article is based on two posts from the “Secrecy News” blog of the Federation of American Scientists, and has been republished here with permission.

(Shana Marshall)

(Shana Marshall)