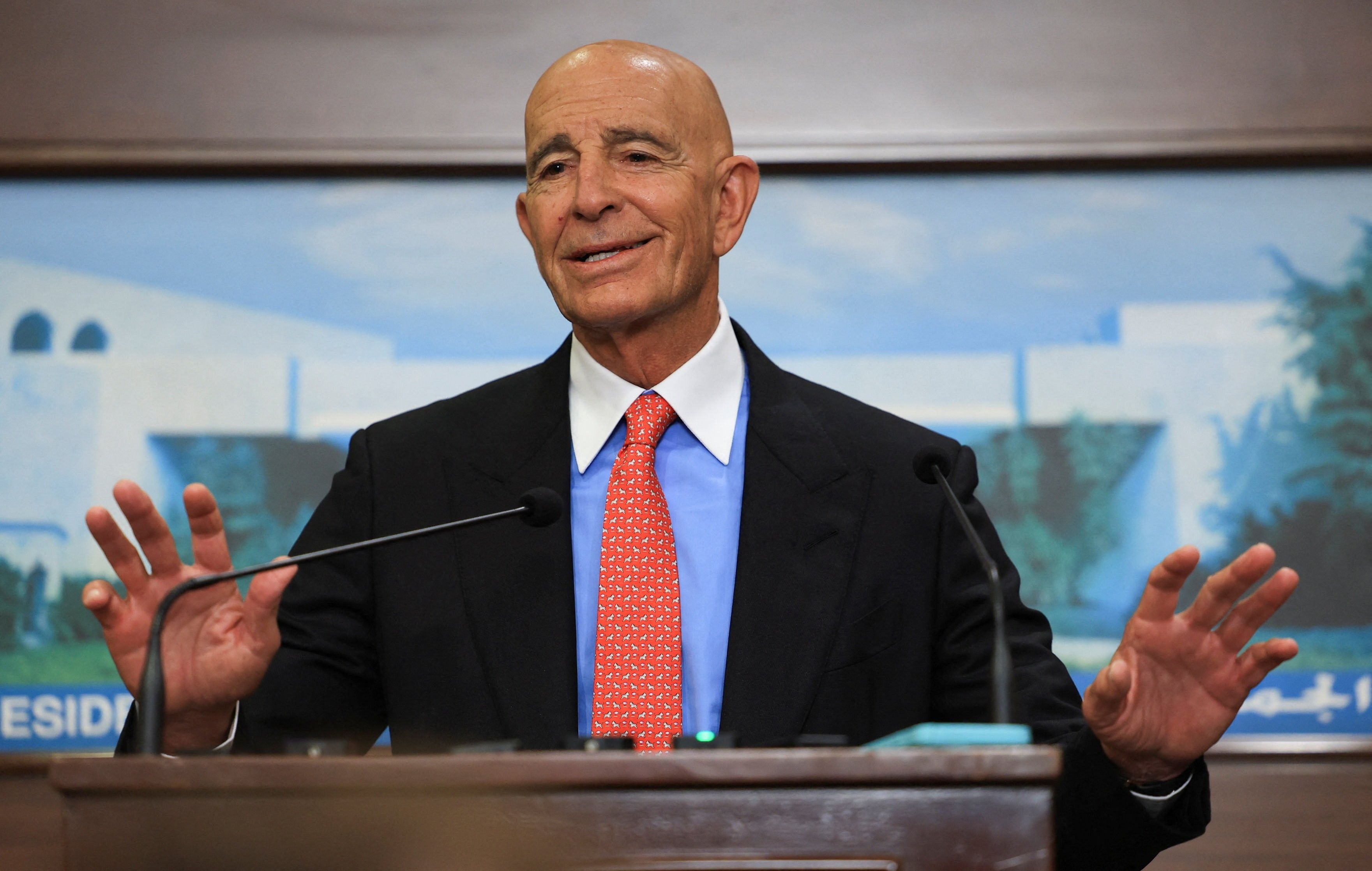

A tale of two envoys recently unfolded in Beirut, encapsulating the crossroads at which Lebanon now stands. Tanned and sporting a pink tie, the U.S. Envoy Tom Barrack arrived with Deputy Special Presidential Envoy to the Middle East, Morgan Ortagus in mid-August. Their meetings with top Lebanese officials underscored Washington’s insistence that lasting stability in Lebanon depends on consolidating state authority, and disarming Hezbollah.

Days earlier, Ali Larijani, the head of Iran’s National Security Council, had departed, leaving a message equally blunt but diametrically opposed: Hezbollah’s arms are a red line and are necessary tools for its “resistance” to Israel. These visits represent the opposing magnetic poles pulling at the country.

Lebanon is reeling from a confluence of catastrophes. A devastating scuffle with Israel last year decapitated Hezbollah’s leadership and ravaged its strongholds. Compounding this military blow was a strategic amputation: the swift collapse of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in Syria, which severed the critical land bridge that for decades funneled Iranian arms and support to Iran’s most prized regional proxy. Into this vortex has stepped Barrack, a 40-year friend of Donald Trump and a businessman by trade, embodying a U.S. strategy that is quintessentially Trumpian in its DNA.

The American proposal, relentlessly pushed by Barrack in marathon meetings from Jerusalem to Beirut, eschews ideology for incentives. It is a carefully sequenced, "step-by-step" plan designed to untie the Gordian knot of southern Lebanon.The Lebanese government, led by former army chief President Joseph Aoun, must take concrete actions to implement its own historic cabinet decision to disarm Hezbollah. As Beirut makes progress, Israel is expected to reciprocate, beginning with a phased withdrawal from the five military outposts it still occupies inside Lebanon and a reduction in its routine airstrikes within Lebanese territory, actions that have continued despite a November 2024 ceasefire.

Yet, true to the spirit of a purported dealmaker president, the core of the strategy is a buyout of Hezbollah’s economy of resistance, replacing it with an economy of reconstruction. The plan's centerpiece is the proposed "economic zone" in southern Lebanon.

Recognizing that Hezbollah’s power is rooted as much in patronage as in piety, the plan aims to substitute Iranian funding and Hezbollah’s shadow economy with a surge of Saudi and Qatari investment, specifically designed to offer new livelihoods to tens of thousands of Hezbollah fighters. Barrack articulated this vision bluntly. "What are you going to do with them?" he asked. "Take their weapon and say ‘by the way, good luck planting olive trees’? It can’t happen. We have to help them."

The plan is designed to achieve two goals at once: to dismantle the group's arsenal in the near-term, and to re-engineer the conditions of state neglect and economic grievance that allowed Hezbollah to flourish in the first place.

This political-commercial nexus is especially evident in the second, quieter dimension of Barrack’s mission: the business of borders and energy. The demarcation of Lebanon’s maritime boundaries, first with Israel and now with Syria, is the essential legal groundwork required to de-risk the Eastern Mediterranean for major American and European energy corporations.

As energy experts have noted, Big Oil firms like Chevron and ExxonMobil will not invest in exploration and extraction in blocks adjacent to a war zone. The American “green light” for investment is conditional on a stable, predictable security environment — one in which a non-state actor like Hezbollah cannot trigger a regional conflagration.

Thus, border demarcation, disarmament, and investment (on land and sea) form an unbreakable chain. A stable border with Syria is necessary for Damascus to begin its own offshore licensing rounds. A stable border with Israel is necessary for Lebanon to attract the capital it desperately needs. And for both to be stable, Hezbollah’s autonomous military capability must be neutralized. Barrack’s plan is a comprehensive effort to establish the political and security prerequisites for a new energy-driven economy in the region, with Lebanon and a post-Assad Syria as junior partners.

The Lebanese cabinet’s approval in early August of a Lebanese army-led disarmament plan was an unprecedented defiance of the state-within-a-state that Hezbollah has operated for decades. However, to expect a simple capitulation is to fundamentally misunderstand the organization.

For generations, Hezbollah has been more than a fighting force, it has been a provider of social services for Lebanon's Shiites and the purveyor of a potent narrative of dignity and resistance against Israeli aggression. The new American-led proposal offers jobs and investment, but it demands the surrender of the very weapons that many in the community believe guarantee their security and political relevance.

This re-engineering extends beyond economics to the entire security architecture of Lebanon’s south. The long-standing U.N. peacekeeping force, the United Nations Interim Force in Lebanon (UNIFIL), is recast through Barrack’s unforgiving business lens as a failed investment — a billion-dollar-a-year venture that has left Lebanon, in his words, "in a swamp." The true answer, he insists, is the Lebanese Armed Forces. Washington’s backing for a final one-year extension of UNIFIL’s mandate is therefore a deadline to operationalize Hezbollah’s disarmament.

This existential fear animates the defiant rhetoric of Hezbollah’s new leader, Naim Qassem. His threats — "whoever wants to take this weapon means they want to take our soul from us…then the world will see our might" — and his framing of disarmament as a humiliating submission to "U.S.-Israeli dictates" are aimed directly at this constituency.

But money talks. The sales pitch at the core of the American-led strategy is to make an offer that Hezbollah's constituents, crippled by Lebanon's economic collapse, cannot refuse. The goal is a hostile takeover of sorts: a buyout of Hezbollah's entire political economy of resistance and its substitution with a new marketplace of reconstruction. The re-engagement of Gulf powers is what puts the capital on the table for this deal, with Saudi Arabia leading the diplomatic charge. After years of frustrated withdrawal, Riyadh has returned with a new policy of "engaged conditionality" — offering the financial support crucial for Lebanon's survival, but strictly conditioned on following Washington’s lead to end Hezbollah’s paramilitary existence.

Where, then, is this heading? The convergence of pressures — military, political, regional, and now economic — on Hezbollah is unprecedented. The path of least resistance, and perhaps the only one that ensures its long-term survival, is for the group to consolidate its immense political gains by sacrificing the military wing that made them possible. This path would compel Hezbollah to finally choose between its two identities: relinquishing its role as a revolutionary vanguard to fully embrace its reality as a powerful, but conventional, parliamentary bloc operating within the confines of the state.

But the underpinnings of this deal are fragile. If the promised economic relief fails to materialize, or if Israel’s reciprocal steps go unfulfilled, the entire enterprise could be exposed as the "U.S.-Israeli dictate" Qassem claims it to be. In that scenario, the Shiite community's fear of being politically neutered will become validated, and Qassem’s threat to “fight” disarmament could become a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Indeed, the deal being brokered by Tom Barrack offers a potential pathway out of decades of conflict, but the approach is seen by some, not as good-faith problem-solving, but as an imposition based on a premature sense of victory. For example, Kim Ghattas, a distinguished fellow at Columbia University’s Institute of Global Politics and an FT contributing editor, argues that the belief Hezbollah would simply capitulate is "sorely deluded.” Hezbollah's identity, Ghattas argues, is transnational, its ultimate loyalty lies not with the Lebanese state but with Iran's Supreme Leader, making a purely national settlement a far more complex proposition.

The sense of an external, top-down imposition was personified by the Barrack himself. His controversial warning to Lebanese journalists to ‘act civilized” and not be “animalistic” was seen by many as deeply offensive. This attitude aligns with the critique from Lebanese academic Hussam Matar, who frames the plan as an attempt at "complete subjugation" rather than a respect for Lebanese sovereignty.

At its heart, the U.S.-led plan to defang Hezbollah demands that a once disenfranchised, now powerful community trade its arms — the very symbol of its identity and security — for a promise. Whether that promise is perceived as an opportunity or a trap will be the deciding factor between a nascent peace and a new civil war..

- US envoy takes lighter touch with Hezbollah in Lebanon ›

- US pressure risks plunging Lebanon into violence | Responsible Statecraft ›